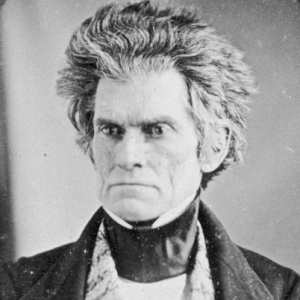

Ever since Richard Hofstadter called John C. Calhoun the “Marx of the Master Class,” at least, American historians have pondered the relationship between the pro-slavery critique of Northern wage labor and later left-wing critiques of capitalism. One of Calhoun’s great themes, as Hofstadter noted, was the inevitable “conflict between labor and capital,” a conflict that threatened to overwhelm the “free institutions” of the North.

Ever since Richard Hofstadter called John C. Calhoun the “Marx of the Master Class,” at least, American historians have pondered the relationship between the pro-slavery critique of Northern wage labor and later left-wing critiques of capitalism. One of Calhoun’s great themes, as Hofstadter noted, was the inevitable “conflict between labor and capital,” a conflict that threatened to overwhelm the “free institutions” of the North.

Unlike Marx, of course, Calhoun and other southerners believed the solution to this problem was not the liberation but the subjugation of the laboring classes. Only the system of human bondage itself had exempted the South from this dangerous class conflict, and only the slaveholding South—the “great conservative power” of the nation, as Calhoun put it—could help preserve the delicate equilibrium between capital and labor in the nonslaveholding states.

Nevertheless the structural parallel between Southern attacks on free labor, and Marxist or otherwise left-wing attacks on capitalism, has fascinated historians for generations. (It would be churlish but not entirely wrongheaded to describe the later career of Eugene Genovese as an extended pursuit of ideological connections between pro-slavery and anti-capitalist thought.)

What sometimes goes missing, then, is the comparatively pedestrian point that actual pro-slavery Southerners had little but disgust for actual left-wing anti-capitalists. In fact there’s a good case to be made that the great right-wing American tradition of denouncing all opposition as “socialist” had its origins among slaveholding elites.

Of course, the history of feverish American hostility to European radicalism goes back far beyond the antebellum decades. But I’m thinking here not about conservative red-baiting in general, but the specific use of the term “socialism.”

Now that the spring semester is over, I’ve returned to my regular habit of reading pro-slavery periodicals. Re-reading an 1850 speech by Virginia Senator Robert M.T. Hunter, reprinted in 1857 by DeBow’s Review, I was struck by this passage: “no government has yet existed, which did not recognize and enforce involuntary servitude for other causes than crime. To destroy that, we must destroy all inequality in property . . . Your socialist is the true abolitionist, and he only fully understands his mission.”

The pro-slavery editor James D.B. Debow called Hunter’s speech “the most thorough vindication of negro slavery ever produced in any deliberative body,” and, befitting the nature of antebellum senatorial debate, Hunter touched on a great many pro-slavery talking points beyond the anti-socialist one.[1] But it got me wondering: when was the first time the word “socialism” (or “socialist”) was used in on the floor of Congress?

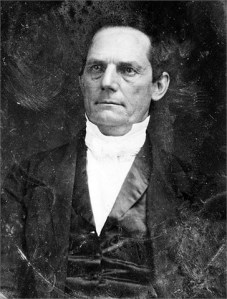

Abraham Watkins Venable: the first congressman to cry “Socialism!”

So I headed over to HeinOnline’s searchable database of the Congressional Globe and plugged in the offending terms.[2] As far as I can make out, the first reference to “socialism” on the floor of Congress came from North Carolina representative Abraham Venable in July 1848. During a debate over the Wilmot Proviso, Venable indulged himself in a familiar litany of destructive Northern manias, which ranged from “the wicked schemes of Garrison” to “the wild excesses of Millerism, and of Latter-Day Saints, the abominations of Socialism, and of Fourieriesm… and all the numerous fanaticisms which spring up and flourish in their free soil…”[3]

This kind of pro-slavery, anti-Northern rant was the context for most mentions of “socialism” in Congress during the next several years. As Karl Marx himself pointed out, once the European revolutions of 1848 encouraged conservatives to identify their opponents with the s-word, they began to do so with mechanical consistency: “the theme remains always the same, the verdict is ever ready and invariably reads: ‘Socialism!’ Even bourgeois liberalism is declared socialistic… bourgeois financial reform socialistic. It was socialistic to build a railway where a canal already existed, and it was socialistic to defend oneself with a cane when one was attacked with a rapier.”[4]

In America, strikingly, it was most socialistic to question the practice of owning property in other human beings.[5] Yet the southern planters who cried “Socialism!” had a better case to make than most conservatives. The anti-slavery movement, in its determination to redefine the idea of property itself, did pose a revolutionary threat to America’s existing political economy.

Calhoun himself, as Hofstadter noted, linked criticism of slavery to criticism of capital as early as 1836: “A very slight modification of the arguments used against the institutions which sustain the property and security of the South would make them equally effectual against the institutions of the North, including banking, in which so vast an amount of property and capital is invested.”

In his 1850 speech, Robert Hunter turned Calhoun’s observation into a prediction: “Sir, it is well that we should consider where these abolition doctrines will lead us. The property holder of the North may experience no inconvenience from them as yet, but his time will come—sooner or later, it must come.”

For many historians, the larger anti-slavery threat to property came during Radical Reconstruction—and then was beaten back by fearful Northern capitalists.[6] Perhaps, as some have recently argued, the property holder’s time will come again. If it does, we can be sure that contemporary conservatives, like their antebellum ancestors, will have no hesitation about dropping the s-bomb.

_________________

[1] One can quibble with DeBow’s politics, but his editorial puffery was second to none. Along with his reprint of Hunter’s address, DeBow added this comment: “It is hard to determine which are most admirable, its learning and research, its chaste, chisel cut, classic language, its calm philosophy, or its excellent temper.”

[2] The text capture transcriptions in Hein’s searchable Congressional Globe are not always foolproof, so it’s possible that my quick search missed earlier references to “socialist” or “socialism.”

[3] Congressional Globe, 30th Congress, 1st Session, Appendix p. 1063 (July 29, 1848). There’s not a lot written about Abraham Venable, but he served as a Democrat in Congress from 1847 to 1853, and then in the Confederate Congress from 1862 to 1864. It may not be a total shock to learn that the first elected official to denounce “socialism” on the floor of Congress was a Princeton man. (He returned to Princeton in June, 1851 to give a commencement address very much in the florid, public-spirited style that Jonathan Wilson wrote about last week.)

[4] Unsurprisingly southerners were very good at this kind of thing, too. My favorite litany of non-socialist socialists comes from the June 1857 issue of DeBow’s Review: “In Western Europe every body is a socialist. No journal and no administration dare defend the established order of things. Louis Napoleon, and Eugenie, are theoretical and practical socialists, and have been engaged in building homes for the laborer; Henry the VI, the Bourbon heir to the throne of France, is an avowed socialist. Mr. Greely informs us that the Queen of England is also a socialist. The Young England party, belonging to the most ultra wing of the Tories, are also socialists, as Coningsby, written by their leader D’Israeli, will show; Carlyle, Dickens, Bulwer, Thackeray, the Clergy, and the Poets of England, are socialists.”

[5] The largely southern and democratic opponents of homestead legislation across the 1850s also frequently denounced land distribution schemes as “socialism.”

[6] David Montgomery, Beyond Equality: Labor and the Radical Republicans, 1862-1872 (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1967); Eric Foner, “Thaddeus Stevens, Confiscation, and Reconstruction,” in Politics and Ideology in the Age of the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980); Heather Cox Richardson, The Death of Reconstruction: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Post-Civil War North, 1865-1901 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001).

Wow, fascinating post! The roots of doctrinaire partisanship run deep….

This is another frame of reference that should be mentioned to folks who think that the Civil War was simply fought “to abolish slavery.”

More on my blogs:

Barley Literate

History: Bottom Lines

Fantastic post.

The 1848 revolutions obviously played a major role, but I suspect we’d find the foundation for this rhetoric of anti-leftist anti-anti-slavery (if you will) in the accusations hurled at the Loco Focos in the 1830s. Venable’s litany of northern radicalisms sounds an awful lot like the accusations William Leggett claimed were being directed at his friends by mainstream Democrats:

[Our readers] have read doubtless a deal of declamation about our ultraism and our Jacobinism; they have seen us called a Utopian, a disciple of Fanny Wright, an agrarian, a lunatic, and a dozen other hard names. They have seen it asserted that we are for overthrowing all the cherished institutions of society; for breaking down the foundations of private right, sundering the marriage tie, and establishing “a community of men, women, and property.”

The immediate concern there was the Loco-Foco critique of corporate banks. But mainstream Democrats’ assertions that the Loco-Focos were beyond the pale of acceptable discourse also grew out of their growing opposition to slavery as a violation of “equal rights” comparable to the outrages committed by banks.

Definitely! My sense is that the rhetoric of “ultraism and Jacobinism”, in a broader sense, was hurled pretty routinely at all sorts of reformers, since at least the first French revolution. (Southerners, too, tremored at the thought that blacks themselves were the true “Jacobins of the country.”)

My guess is that 1848 is mostly significant here because it brought the specific term “socialism” into greater public view. A quick Ngram search seems to confirm this.

Also, Jonathan, I did a bit more digging on Venable — a Princeton man, naturally! — and added his 1851 commencement address to the notes… thought you might be interested given your recent writing on the subject. (Yes, he did use the phrase “knowledge is power”, and he did end the speech with a call for public, patriotic devotion).

Reblogged this on DailyHistory.org and commented:

Matt Karp’s discussion at Junto regarding Calhoun’s solution to preserve through slavery is an interesting story in the Piketty era. Calhoun essentially argued that the only way to preserve capitalism was to enslave workers. In other words, the primary goal of capitalism was preserve the wealth, status and power of a select group of oligarchs.

Pingback: Open Thread–11/16/2014 » Politics Plus

Pingback: Links be a Lady tonight | taylortoowen

Pingback: The Junto Enters the Terrible Twos! « The Junto

Pingback: Quora

Pingback: 2:00PM Water Cooler 8/4/2017 - Daily Economic Buzz