Yesterday, Apple, Facebook, YouTube, and Spotify removed the content of conspiracy theorist Alex Jones from their services. Jones has gained notoriety for propagating outrageous falsehoods on topics including vaccines, school shootings, and uh, *checks notes* space vampires. These decisions to remove Jones’s content come amid a growing public conversation about the extent to which technology and social media companies should act as stewards of truth. Facebook in particular has come under scrutiny for its role in spreading “fake news” in American politics and anti-Muslim propaganda in Sri Lanka, as well as CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s defense of Holocaust deniers’ ability to share verifiably false content on the site. Continue reading

Yesterday, Apple, Facebook, YouTube, and Spotify removed the content of conspiracy theorist Alex Jones from their services. Jones has gained notoriety for propagating outrageous falsehoods on topics including vaccines, school shootings, and uh, *checks notes* space vampires. These decisions to remove Jones’s content come amid a growing public conversation about the extent to which technology and social media companies should act as stewards of truth. Facebook in particular has come under scrutiny for its role in spreading “fake news” in American politics and anti-Muslim propaganda in Sri Lanka, as well as CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s defense of Holocaust deniers’ ability to share verifiably false content on the site. Continue reading

Tag Archives: Benjamin Franklin

The Month in Early American History

Rise and shine, it’s time to relaunch our regular(ish) roundup of breaking news from early America. To the links!

Rise and shine, it’s time to relaunch our regular(ish) roundup of breaking news from early America. To the links!

First up, enjoy a walk through life after the American Revolution with this podcast series charting the life and times of William Hamilton of The Woodlands, who “made the estate an architectural and botanical showpiece of early America.” Or put presidential parades in historical context, via Lindsay Chervinsky’s essay on George Washington’s reticence for public pomp and grandeur: “Why, then, did Washington, a man intensely proud of his military service and revered for it, reject the trappings of military honor?” In conference news, the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture unveiled the program for next month’s meeting. Elsewhere in the blogosphere, check out John Fea’s reflections on a decade(!) of posting, and what it means to teach “Public History for a Democracy.” Or flip through the newly digitized papers of polymath Benjamin Franklin. Continue reading

IOTAR50: Paper Politics

All praise to the humble pamphlet, upon which *may* rest the ideological origins of the American Revolution. Frequently buried by history as loose “Bundells of Pamphlets in quarto,” it’s a genre that almost shouldn’t be. Printed on flimsy paper and easily battered by salt spray or avid readers, the popular pamphlet became a clutch genre for British and American revolutionaries to send ideas around the Atlantic World. These publications, along with newsbooks, hardened into the “paper bullets,” that, according to scholar Joad Raymond, flew on and off the page in early modern England’s press.

Even as the genre evolved into weekly newspapers, he writes, “readers recognized the rules of the form.” Pamphlet culture, a dynamic arena for anonymous critics to take an eloquent swipe at matters of church and state, quickly blossomed abroad. Unbound and unfettered, pamphlets seeded colonists with a new political consciousness. Whether 10 pages or 50, these slim booklets amplified republican politics and revolutionary prose. Pamphlets, as Robert G. Parkinson observes, became the “lifeblood” of the American Revolution. “They instructed the colonial public that political and personal liberty were in jeopardy because British imperial reformers sought to strip them of their natural rights, especially the right to consent to a government that could hear and understand them,” he writes. Today, let’s look at that instructional aspect of pamphlet culture, and how Bernard Bailyn’s interpretation of revolutionary tracts has reshaped what we do in public history. Continue reading

Roundtable: Q & A with Laurie Halse Anderson

Thanks to all of our contributors and commentators who have participated in #FoundingFiction, a series revisiting children’s and young adult literature about early America. Today, Sara Georgini wraps up the roundtable by chatting with Laurie Halse Anderson, prize-winning author of Independent Dames, Fever 1793, Chains, Forge, Ashes, and more. Continue reading

Thanks to all of our contributors and commentators who have participated in #FoundingFiction, a series revisiting children’s and young adult literature about early America. Today, Sara Georgini wraps up the roundtable by chatting with Laurie Halse Anderson, prize-winning author of Independent Dames, Fever 1793, Chains, Forge, Ashes, and more. Continue reading

Roundtable: Telling the Story of the Declaration

Today’s Founding Fiction post is by Emily Sneff, Research Manager of the Declaration Resources Project at Harvard University. The mission of the Declaration Resources Project is to create innovative and informative resources about the Declaration of Independence. To learn more, follow @declarationres.

How do we get kids to read and comprehend the Declaration of Independence? Great authors and illustrators can transform the characters, events, and text of the Declaration (which, as you may expect, registers at about a 12th grade reading level) into true stories that are both entertaining and educational for younger readers. On the Declaration Resources Project’s blog, Course of Human Events, we recently interviewed authors Barbara Kerley (Those Rebels, John & Tom), Steve Sheinkin (King George: What Was His Problem? The Whole Hilarious Story of the American Revolution), and Gretchen Woelfle (Answering the Cry for Freedom: Stories of African Americans and the American Revolution). Their books, and a few other favorites, form an exciting non-fiction reading list for children and young adults. Continue reading

Roundtable: Crafting Protest, Fashioning Politics: DIY Lessons from the American Revolution

This Colonial Couture post is by Zara Anishanslin, assistant professor of history and art history at the University of Delaware. Her latest book is Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World (Yale University Press, 2016). Follow her @ZaraAnishanslin.

Homespun, Thomas Eakins, 1881, Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Please, sisters, back away from the pink.”

So women planning to attend the January 2017 Women’s Marches were urged by the writer of an opinion piece in The Washington Post. “Sorry knitters,” she continued, but making and wearing things like pink pussycat hats “undercuts the message that the march is trying to send….We need to be remembered for our passion and purpose, not our pink pussycat hats.” To back up her point, the author opined that “bra burning” dominated—and thus damaged—popular (mis)conceptions of women’s rights protests in the 1960s. Please, ladies, she exhorted, don’t repeat the mistakes we made in the ‘60s by bringing fashion into politics. Continue reading

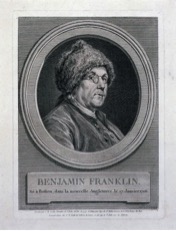

Roundtable: Ambassador in a Hat: The Sartorial Power of Benjamin Franklin’s Fur Cap

This Colonial Couture post is by guest contributor Joanna M. Gohmann, Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow in 18th– and 19th-Century Art, at The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

Benjamin Franklin (Augustin de Saint Aubin after Charles Nicholas Cochin, 1777, private collection)

While acting as the American ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin wore a fur hat to express his American status. The French enthusiastically accepted Franklin’s use of the topper, seeing it as an embodiment of the ambassador and a symbol of America and the American cause. When he first came to France in 1767, Franklin wore the clothes of a polite, fashionable Frenchman—a fine European suit and powdered wig—as a way to show respect to the French court. When he returned in 1776, he abandoned all the decorum of French dress and instead wore a simple, homespun brown suit, spectacles, and a large fur hat. He cleverly adopted this style as a way to garner attention and appeal to the French for support of the American cause.[1]

Men of La Mancha

In a certain village of vast early America, whose name I do not recall, a book fell open. Then another. And another. By 1860, many generations’ worth of American readers had imbibed the two-volume work of Spain’s early modern master, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: Don Quixote, or, El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de La Mancha (1605). Cervantes’ metafiction of a mad knight-errant, often hailed as the first Western novel, bustled and blistered with originality. Continue reading

In a certain village of vast early America, whose name I do not recall, a book fell open. Then another. And another. By 1860, many generations’ worth of American readers had imbibed the two-volume work of Spain’s early modern master, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: Don Quixote, or, El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de La Mancha (1605). Cervantes’ metafiction of a mad knight-errant, often hailed as the first Western novel, bustled and blistered with originality. Continue reading

“In the Service of the Crown ever since I came into this Province”: The Life and Times of Cadwallader Colden

John M. Dixon, The Enlightenment of Cadwallader Colden: Empire, Science, and Intellectual Culture in British New York (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2016).

On December 8, 1747, Gov. George Clinton (1686–1761) told a British statesman that the Assembly of New York “treated the person of the Governor with such contempt of his authority & such disrespect to the noble family where he had his birth that must be of most pernicious example.” He thought he might have to “give it [i.e., his position] up to a Faction.” The extant copy of this letter, held within Clinton’s papers at the William L. Clements Library in Michigan, was written by his most trusted advisor and ally—Cadwallader Colden, the subject of John M. Dixon’s first book, The Enlightenment of Cadwallader Colden: Empire, Science, and Intellectual Culture in British New York, published in 2016 by Cornell University Press.[1]

On December 8, 1747, Gov. George Clinton (1686–1761) told a British statesman that the Assembly of New York “treated the person of the Governor with such contempt of his authority & such disrespect to the noble family where he had his birth that must be of most pernicious example.” He thought he might have to “give it [i.e., his position] up to a Faction.” The extant copy of this letter, held within Clinton’s papers at the William L. Clements Library in Michigan, was written by his most trusted advisor and ally—Cadwallader Colden, the subject of John M. Dixon’s first book, The Enlightenment of Cadwallader Colden: Empire, Science, and Intellectual Culture in British New York, published in 2016 by Cornell University Press.[1]

Teaching History Without Chronology

Most history courses follow a relatively simple formula: take a geographic space X, select a time span from A to B, add topics, and you’ve got yourself a course. It varies, of course, but works for both introductory courses, where you might survey the political, social, and cultural development of the people living in a geographic area, to upper-level courses with topical focuses. As a field whose primary concern is change over time, that formula makes sense. That consistency also means that students expect it from their high school and college history courses. And how else would you organize a history course?

Most history courses follow a relatively simple formula: take a geographic space X, select a time span from A to B, add topics, and you’ve got yourself a course. It varies, of course, but works for both introductory courses, where you might survey the political, social, and cultural development of the people living in a geographic area, to upper-level courses with topical focuses. As a field whose primary concern is change over time, that formula makes sense. That consistency also means that students expect it from their high school and college history courses. And how else would you organize a history course?

I found out last semester.