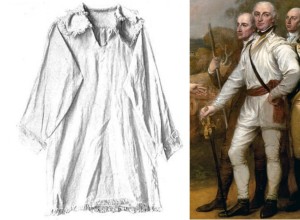

Photograph in Charles Knowles Bolton, The Private Soldier Under Washington, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1902, p. 162 and detail from The Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga, October 16, 1777, Yale University Art Gallery.

The following post is a guest post from Marta Olmos. Marta Olmos received her BA in History from Cornell University and her MLitt in Scottish History from the University of Glasgow. She works in public history and interpretation at Minute Man National Historic Park in Concord, MA. She is on Twitter @almostmartita

In her 1988 article Rayna Green said that “one of the oldest and most pervasive forms of American cultural expression… is a ‘performance’ I call ‘playing Indian.’” The Indian, in this context, is an amalgamation of white stereotypes of Native people, and the performance of “playing Indian” is carried out by white bodies, using the Indian to explore their own identities, fears, and cultures.[1] As the American Revolution dawned, the Indian was everywhere. Hunting shirts, the makeshift uniform of the Continental Army, were at the center of a movement around “playing Indian.” By exploring the discourse around the hunting shirt, and the performance of “playing Indian” that accompanied it, we can better understand the role of the Indian, and backcountry culture, in forging an early American military identity during the early 1770s.[2] Continue reading