As we continue to learn more about the seizure and internment of migrant infants and children, both along the U.S.-Mexico border and in ICE raids throughout the nation, historians have asked us to wrestle with our long history of child-snatching, family separation, and child trafficking. I’ve read these pieces with a keen sense that while this is a particularly acute theme in American history, separating and abducting children from their families has been a tactic that many regimes have used for centuries to bolster their power. Whether we’re discussing slavery, the expulsion of Moriscos from Spain, or even pronatalist policies to populate early modern colonies, trafficking children has been an enduring state tactic. As a historian of #VastEarlyAmerica, with a focus on the French context, I keep thinking about the growth of the Louisiana colony in the eighteenth century. In addition to the forced migration and abduction of thousands of enslaved Africans, many of whom were children and adolescents, eighteenth-century French Louisiana was also populated with trafficked French children. Continue reading

As we continue to learn more about the seizure and internment of migrant infants and children, both along the U.S.-Mexico border and in ICE raids throughout the nation, historians have asked us to wrestle with our long history of child-snatching, family separation, and child trafficking. I’ve read these pieces with a keen sense that while this is a particularly acute theme in American history, separating and abducting children from their families has been a tactic that many regimes have used for centuries to bolster their power. Whether we’re discussing slavery, the expulsion of Moriscos from Spain, or even pronatalist policies to populate early modern colonies, trafficking children has been an enduring state tactic. As a historian of #VastEarlyAmerica, with a focus on the French context, I keep thinking about the growth of the Louisiana colony in the eighteenth century. In addition to the forced migration and abduction of thousands of enslaved Africans, many of whom were children and adolescents, eighteenth-century French Louisiana was also populated with trafficked French children. Continue reading

Tag Archives: France

Guest Post: French Imposters, Diplomatic Double Speak, and Buried Archival Treasures

Today’s guest post is by Cassandra Good, Associate Editor of The Papers of James Monroe at the University of Mary Washington, and author of Founding Friendships: Friendships Between Women and Men in the Early American Republic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015). Follow her @CassAGood.

The latest volume of The Papers of James Monroe covers a short but important period in Monroe’s life and career: April 1811 to March 1814. Monroe became Secretary of State in April 1811 and was tasked with trying to repair relations with both Great Britain and France. After war with Britain began in June 1812, his focus broadened to military affairs and included a stint as interim Secretary of War. The bulk of the volume, then, is focused on the War of 1812. However, there are a number of other stories revealed here that will be of interest to a range of historians. Continue reading

The latest volume of The Papers of James Monroe covers a short but important period in Monroe’s life and career: April 1811 to March 1814. Monroe became Secretary of State in April 1811 and was tasked with trying to repair relations with both Great Britain and France. After war with Britain began in June 1812, his focus broadened to military affairs and included a stint as interim Secretary of War. The bulk of the volume, then, is focused on the War of 1812. However, there are a number of other stories revealed here that will be of interest to a range of historians. Continue reading

Roundtable: Crafting Protest, Fashioning Politics: DIY Lessons from the American Revolution

This Colonial Couture post is by Zara Anishanslin, assistant professor of history and art history at the University of Delaware. Her latest book is Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World (Yale University Press, 2016). Follow her @ZaraAnishanslin.

Homespun, Thomas Eakins, 1881, Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Please, sisters, back away from the pink.”

So women planning to attend the January 2017 Women’s Marches were urged by the writer of an opinion piece in The Washington Post. “Sorry knitters,” she continued, but making and wearing things like pink pussycat hats “undercuts the message that the march is trying to send….We need to be remembered for our passion and purpose, not our pink pussycat hats.” To back up her point, the author opined that “bra burning” dominated—and thus damaged—popular (mis)conceptions of women’s rights protests in the 1960s. Please, ladies, she exhorted, don’t repeat the mistakes we made in the ‘60s by bringing fashion into politics. Continue reading

Roundtable: Ambassador in a Hat: The Sartorial Power of Benjamin Franklin’s Fur Cap

This Colonial Couture post is by guest contributor Joanna M. Gohmann, Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow in 18th– and 19th-Century Art, at The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

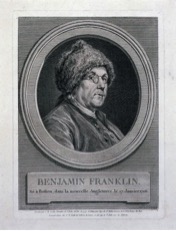

Benjamin Franklin (Augustin de Saint Aubin after Charles Nicholas Cochin, 1777, private collection)

While acting as the American ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin wore a fur hat to express his American status. The French enthusiastically accepted Franklin’s use of the topper, seeing it as an embodiment of the ambassador and a symbol of America and the American cause. When he first came to France in 1767, Franklin wore the clothes of a polite, fashionable Frenchman—a fine European suit and powdered wig—as a way to show respect to the French court. When he returned in 1776, he abandoned all the decorum of French dress and instead wore a simple, homespun brown suit, spectacles, and a large fur hat. He cleverly adopted this style as a way to garner attention and appeal to the French for support of the American cause.[1]

“Terrorism” in the Early Republic

Late last week, Americans learned about an armed takeover of a federal wildlife refuge in Oregon. It was initiated by a group of men who have an idiosyncratic understanding of constitutional law and a sense that they have been cheated and persecuted by the United States government. The occupation comes during a time of general unease about national security and fairness in policing. As a result, some critics have been calling the rebels “domestic terrorists,” mostly on hypothetical grounds. One of their leaders, on the other hand, told NBC News that they see themselves as resisting “the terrorism that the federal government is placing upon the people.”

Late last week, Americans learned about an armed takeover of a federal wildlife refuge in Oregon. It was initiated by a group of men who have an idiosyncratic understanding of constitutional law and a sense that they have been cheated and persecuted by the United States government. The occupation comes during a time of general unease about national security and fairness in policing. As a result, some critics have been calling the rebels “domestic terrorists,” mostly on hypothetical grounds. One of their leaders, on the other hand, told NBC News that they see themselves as resisting “the terrorism that the federal government is placing upon the people.”

I do not propose to address the Oregon occupation directly. However, since the topic keeps coming up lately, this seems like a good opportunity to examine the roles the word terrorism has played in other eras. As it turns out, Americans have been calling each other terrorists a long time.

Roundtable: Academic Book Week—On Trade/Craft

The baker’s nod, the knight’s blade, the king’s touch: These are three of the main and mostly medieval reasons why I read and write American history. Over the past few days, we’ve lauded new writing blueprints, parsed the definition of an academic book, and even made good sport of the whole reading selection process. So, in the last, spooling print loop of Academic Book Week, let’s rewind the too-short life of Marc Bloch for tradecraft’s sake. Continue reading

The baker’s nod, the knight’s blade, the king’s touch: These are three of the main and mostly medieval reasons why I read and write American history. Over the past few days, we’ve lauded new writing blueprints, parsed the definition of an academic book, and even made good sport of the whole reading selection process. So, in the last, spooling print loop of Academic Book Week, let’s rewind the too-short life of Marc Bloch for tradecraft’s sake. Continue reading

A Toast to John Adams

Happy 280th birthday to President John Adams: lawyer, statesman, and…wine connoisseur? He began a crisp New England morning like today with a tankard of hard cider, but Adams’ years in Europe primed his palate for fine French wine. Continue reading

Happy 280th birthday to President John Adams: lawyer, statesman, and…wine connoisseur? He began a crisp New England morning like today with a tankard of hard cider, but Adams’ years in Europe primed his palate for fine French wine. Continue reading

History & Story

Once or twice upon a chapter, as you work to tell history as story, take comfort in knowing that even American sage Henry Adams sometimes had a not-great writing day. By 1878, the 40-year-old Harvard professor of medieval history was a polished scholar. Hailing from a family that wrote for the archive, he navigated easily the uncatalogued byways of an early Library of Congress. He swept up obscure state records and gathered local maps for his 9-volume History of the United States. As editor of the North American Review, Henry instructed freelancers to write “in bald style.” He sliced his private letters down to acid cultural commentary that, to the modern reader, feels meta-enough to border on code. Continue reading

Once or twice upon a chapter, as you work to tell history as story, take comfort in knowing that even American sage Henry Adams sometimes had a not-great writing day. By 1878, the 40-year-old Harvard professor of medieval history was a polished scholar. Hailing from a family that wrote for the archive, he navigated easily the uncatalogued byways of an early Library of Congress. He swept up obscure state records and gathered local maps for his 9-volume History of the United States. As editor of the North American Review, Henry instructed freelancers to write “in bald style.” He sliced his private letters down to acid cultural commentary that, to the modern reader, feels meta-enough to border on code. Continue reading

The Week in Early American History

It’s commencement season around the United States, so we wish a hearty congratulations to all of our readers (and our students) graduating this month. Now, straight on to the links!

It’s commencement season around the United States, so we wish a hearty congratulations to all of our readers (and our students) graduating this month. Now, straight on to the links!

Guest Post: Keeping the “Human” in the Humanities

Hannah Bailey is a PhD candidate in History at the College of William & Mary, where her research examines the interconnectivity between developing notions of race and the expansion of the African slave trade in the early modern French Atlantic. This is her second guest post at The Junto. Be sure and read her earlier post on French archives and entangled histories here.

As someone who is also leaping into an entirely new historiography in preparation for dissertation writing, I could commiserate with Casey Schmitt’s brilliantly astute post on the costs and benefits of comparative projects. It can be terrifying to move from a historiography with which one is relatively comfortable to, as she puts it, “a [new] field where innumerable scholars have dedicated entire careers.” I took one undergraduate class on West African history (which was a survey course that occurred five years ago), and yet my dissertation focuses heavily on early modern histories of West Africa and the Atlantic networks of knowledge (and ignorance) that shaped them. The body of exemplary secondary source material on West Africa is vast, and working with it for the first time is more than a little daunting. Continue reading

As someone who is also leaping into an entirely new historiography in preparation for dissertation writing, I could commiserate with Casey Schmitt’s brilliantly astute post on the costs and benefits of comparative projects. It can be terrifying to move from a historiography with which one is relatively comfortable to, as she puts it, “a [new] field where innumerable scholars have dedicated entire careers.” I took one undergraduate class on West African history (which was a survey course that occurred five years ago), and yet my dissertation focuses heavily on early modern histories of West Africa and the Atlantic networks of knowledge (and ignorance) that shaped them. The body of exemplary secondary source material on West Africa is vast, and working with it for the first time is more than a little daunting. Continue reading