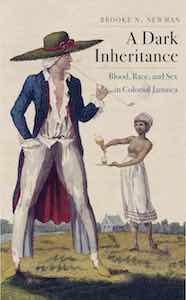

Today, The Junto features a Q&A with Brooke Newman,  author of A Dark Inheritance: Blood, Race, and Sex in Colonial Jamaica (Yale, 2018), which was a finalist for the Gilder Lehrman Center’s 2019 Frederick Douglass Book Prize for the best work in English on slavery, resistance, and/or abolition. Her research focuses on the intersections of race, sexuality, and gender in the context of slavery and abolition in the British empire, focusing on the Caribbean. Newman is an Associate Professor of History at Virginia Commonwealth University, where she is also Interim Director of the Humanities Research Center. Look for a review of A Dark Inheritance later this spring.

author of A Dark Inheritance: Blood, Race, and Sex in Colonial Jamaica (Yale, 2018), which was a finalist for the Gilder Lehrman Center’s 2019 Frederick Douglass Book Prize for the best work in English on slavery, resistance, and/or abolition. Her research focuses on the intersections of race, sexuality, and gender in the context of slavery and abolition in the British empire, focusing on the Caribbean. Newman is an Associate Professor of History at Virginia Commonwealth University, where she is also Interim Director of the Humanities Research Center. Look for a review of A Dark Inheritance later this spring.

Tag Archives: Abolitionism

Why We Will Not Go

How and why does a group in a society feel affection for the society they live in, despite the constant abuses faced by them? A great case study to help answer the question is through the anti-slavery movement. Boston abolitionist intellectual Maria Stewart, after the loss of both her husband, James Stewart and intellectual mentor, abolitionist David Walker in 1830, refocused her life on Jesus and fighting for her race. From that foundation, she met and collaborated with upstart white abolitionist newspaper editor William Lloyd Garrison of The Liberator. Garrison was a major influence on Stewart’s public career because Garrison promoted Stewart as a voice of her people, and the Liberator offered her room to publicly debate the best policies for her race’s future. In one of Stewart’s published writings in the Liberator, she wrote about death to the body of the enslaved, that would also free the soul. “The blood of her murdered ones cries to heaven for vengeance against thee. Thou art almost drunken with the blood of her slain.[1]” The plunder of black bodies effectively built the United States, and based upon Stewart’s interpretation, America became drunk from its excess. Continue reading

Sarah Parker Remond: Black Abolitionist Diplomat

The meaning of the American Civil War has been, and still is, one of the most contentious issues facing the United States today. An aspect of the war that seems to be less spoken about though, was the role of Black women internationally during the Civil War. Wars of the scale of the American Civil War rarely lack an internationalist component. For the already internationalist American abolitionist movement, when the Civil War began in 1861, the abolitionist struggle shifted south with the work of women like Harriet Tubman and Charlotte Forten, but there were still important battles being waged internationally over the war and its meaning.

The Black woman who took the international abolitionist stage during the Civil War was Salem, Massachusetts’ Sarah Parker Remond. After having been in the British Isles for almost two years prior to the war, Remond’s abolitionist tour expressed a stronger sense of urgency, as the war provided a tangible arena for potential ending of slavery. While doing so, she developed notions of performative citizenship. Performative citizenship was an aspirational basis of struggle for realized citizenship based on Black abolitionist women’s proclamations of African-American identities. Those identities were based on economic and intellectual analyses of the central role their race’s plunder played in American economic growth. Continue reading

Black Women Intellectuals and the Politics of Dislocation

In light of the recent tragic stories of family separation occurring on the Mexico-United States border, what instantly came to my mind was America’s history of dislocation through American slavery. From the United States’s conception, the place of the country’s Black population, enslaved and free, was centered in debates on who this country was ultimately built for. There were factions that saw slavery as antithetical to the founding principles of “freedom, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” During the Revolutionary War, even British orators like Samuel Johnson, clearly saw this dichotomy. In his 1775 pamphlet Taxation No Tyranny: An Answer To The Resolutions And Address Of The American Congress, Johnson juxtaposed the colonist’s “Declaration of Rights,” and equivocated “If [s]lavery be thus fatally contagious, how is it that we hear the loudest yelps of for liberty among the drivers of negroes.”[1] Not all factions of the founding generation decidedly occupied one camp of pro-slavery or anti-slavery though. America’s first and third presidents denoted this friction. Washington and Jefferson’s stories denoted both held surface level anti-slavery positions, yet also owned hundreds of bondswomen and men; very similar to what Johnson characterized. This complication stemmed from the generation’s refusal to resolve the “slavery question” that plagued the new nation. Political compromises, like the counting of enslaved peoples as three-fifths a person, prolonged America’s reckoning, but only temporarily. However, a middle ground emerged by the early 19th century: colonization. Continue reading

The Month in Early American History

Rise and shine, it’s time to relaunch our regular(ish) roundup of breaking news from early America. To the links!

Rise and shine, it’s time to relaunch our regular(ish) roundup of breaking news from early America. To the links!

First up, enjoy a walk through life after the American Revolution with this podcast series charting the life and times of William Hamilton of The Woodlands, who “made the estate an architectural and botanical showpiece of early America.” Or put presidential parades in historical context, via Lindsay Chervinsky’s essay on George Washington’s reticence for public pomp and grandeur: “Why, then, did Washington, a man intensely proud of his military service and revered for it, reject the trappings of military honor?” In conference news, the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture unveiled the program for next month’s meeting. Elsewhere in the blogosphere, check out John Fea’s reflections on a decade(!) of posting, and what it means to teach “Public History for a Democracy.” Or flip through the newly digitized papers of polymath Benjamin Franklin. Continue reading

Guest Review: Benjamin Park, American Nationalisms

Skye Montgomery is a historian of the nineteenth-century United States, specializing in Anglo-American relations and the transformation of American national identity. She is currently completing a postdoctoral fellowship at the Kinder Institute on Constitutional Democracy at the University of Missouri-Columbia. Skye earned her DPhil in History at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, and is revising a book manuscript entitled, Imagined Families: Anglo-American Kinship and the Formation of Southern Identity, 1830-1890.

Benjamin E. Park, American Nationalisms: Imagining Union in the Age of Revolutions, 1783-1833 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

In his seminal 1882 lecture, Ernest Renan posed the deceptively straightforward question, “What is a Nation?” Although recent historiography is generally more concerned with answering the adjacent questions of how and why nations come to be, scholars of European history have produced myriad reflections on Renan’s question in the decades since the Second World War. In contrast, however, histories of early America taking nationalism as their primary category of analysis have been relatively few and focused primarily upon understandings of nationalism yoked to the nation-state. Benjamin Park’s new volume, American Nationalisms: Imagining Union in the Age of Revolutions, 1783-1833, offers a convincing explanation for this omission and makes commendable strides towards rectifying it. Continue reading

Graphic Novels Roundtable Q & A: Ari Kelman, Battle Lines: a Graphic Novel of the Civil War

We continue day three of our graphic novels roundtable with an interview with historian Ari Kelman, who co-authored Battle Lines: a Graphic History of the Civil War. Previously Jessica Parr discussed using graphic novels to explore painful histories and Roy Rogers reviewed Rebels from Dark Horse Comics.

Ari Kelman is the McCabe Greer Professor of History at Pennsylvania State University, specializing in the Civil War, Reconstruction, Memory Politics, and Environmental History. In addition to Battle Lines: a Graphic Novel of the Civil War, he is the author of two award-winning books. A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling Over the Memory of Sand Creek (Harvard, 2013) was the recipient of the Bancroft Prize, the Avery Craven Award, the the Tom Watson Brown Book Award, and the Robert M. Ultey Prize. A River and Its City: The Nature of Landscape in New Orleans (University of California Press, 2003) won the Abbott Lowell Cummings Prize. Continue reading

Ari Kelman is the McCabe Greer Professor of History at Pennsylvania State University, specializing in the Civil War, Reconstruction, Memory Politics, and Environmental History. In addition to Battle Lines: a Graphic Novel of the Civil War, he is the author of two award-winning books. A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling Over the Memory of Sand Creek (Harvard, 2013) was the recipient of the Bancroft Prize, the Avery Craven Award, the the Tom Watson Brown Book Award, and the Robert M. Ultey Prize. A River and Its City: The Nature of Landscape in New Orleans (University of California Press, 2003) won the Abbott Lowell Cummings Prize. Continue reading

Teaching Trauma: Narrative and the Use of Graphic Novels in Discussing Difficult Pasts

Roy Rogers kicked off yesterday’s 4-day roundtable with a review of the graphic novel, Rebel. For day two of our roundtable on graphic novels and history, I will discuss the use of graphic novels in teaching traumatic histories.

As anyone who has taught the history of slavery knows, it can be challenging. It is an important, but also emotionally loaded subject that can provoke spirited responses from students. Some students are resistant to discussing what they view as an ugly event in the past. Others may become defensive. And, for others, the history of slavery may be personal. The challenge becomes presenting the history in a thoughtful way that will engage students, but does not whitewashing history. Other traumatic events—genocide, war, etc.—can present similar pedagogical challenges.

As anyone who has taught the history of slavery knows, it can be challenging. It is an important, but also emotionally loaded subject that can provoke spirited responses from students. Some students are resistant to discussing what they view as an ugly event in the past. Others may become defensive. And, for others, the history of slavery may be personal. The challenge becomes presenting the history in a thoughtful way that will engage students, but does not whitewashing history. Other traumatic events—genocide, war, etc.—can present similar pedagogical challenges.

Remembering Christopher Schmidt-Nowara, 1966-2015

Historian Christopher Schmidt-Nowara passed away suddenly in Paris on Saturday, June 27th at the age of 48. Schmidt-Nowara was a prolific chronicler of the history of slavery and emancipation in the Hispanic world, as well as politics and ideas in the Spanish empire. He received his B.A. from Kenyon College in 1988. He completed his PhD from the University of Michigan in 1995, under the direction of Rebecca Scott, and taught at Fordham University in New York City for over a decade before joining the faculty at Tufts University in 2011. At the time of his death, he was Prince of Asturias Chair of Spanish Culture and Civilization at Tufts.

Historian Christopher Schmidt-Nowara passed away suddenly in Paris on Saturday, June 27th at the age of 48. Schmidt-Nowara was a prolific chronicler of the history of slavery and emancipation in the Hispanic world, as well as politics and ideas in the Spanish empire. He received his B.A. from Kenyon College in 1988. He completed his PhD from the University of Michigan in 1995, under the direction of Rebecca Scott, and taught at Fordham University in New York City for over a decade before joining the faculty at Tufts University in 2011. At the time of his death, he was Prince of Asturias Chair of Spanish Culture and Civilization at Tufts.

The Week in Early American History

We begin this Week in Early American History with James Oakes’ powerful and timely reflection on white abolitionism. “The Real Problem with White Abolitionists,” Oakes argues, is that “even the most radical abolitionists betrayed a blind faith in the magical healing powers of a free market in labor. Scarcely a single theme of the broader antislavery argument strayed far from the premise.”

We begin this Week in Early American History with James Oakes’ powerful and timely reflection on white abolitionism. “The Real Problem with White Abolitionists,” Oakes argues, is that “even the most radical abolitionists betrayed a blind faith in the magical healing powers of a free market in labor. Scarcely a single theme of the broader antislavery argument strayed far from the premise.”

Continue reading