Stella McCartney Spring/Summer 2018 ready-to-wear fashion collection, Paris, Oct. 2, 2017. (AP Photo/Francois Mori)

Today’s #ColonialCouture post is by Bronwen Everill, lecturer in history at Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge University, and author of Abolition and Empire in Sierra Leone and Liberia, Cambridge Series in Imperial and Post-colonial Studies (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). Follow her @BronwenEverill.

In 2017, Stella McCartney ran into trouble during Paris fashion week. Her faux pas was cultural appropriation: using Nigerian Ankara fabrics, reportedly pretending to have “discovered” them, and dressing her almost exclusively white group of models in the fabric.

In 1791, British traveller Anna Maria Falconbridge complained of the failure of her own attempt to promote cultural appropriation of European fashions, while describing her visit to the Temne, in Sierra Leone, West Africa. Spending time with Clara, the wife of the royal secretary, “I endeavoured to persuade her to dress in the European way, but to no purpose; she would tear the clothes off her back immediately after I put them on. Finding no credit could be gained by trying to new fashion this Ethiopian Princess, I got rid of her as soon as possible.”[1] Now, maybe it’s just me, but I always think Anna Maria would have given Gretchen Wieners a run for her money as Regina George’s BFF. Her book, Two Voyages in Sierra Leone, is full of snarky comments about fashion in Sierra Leone, but it comes across as so much posturing.

-

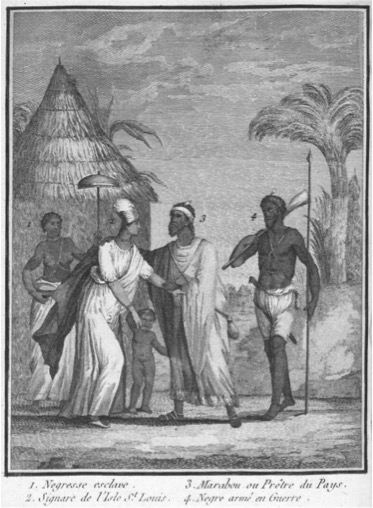

Dominique Harcourt Lamiral, L’Afrique et le peuple afriquain, considérés sous tous leurs rapports avec notre commerce et nos colonies, 1789, 81 / Source: Digital NYPL

But like Stella McCartney, Anna Maria was not the first to “discover” African fashion; she was just joining in an eighteenth century trend of reporting what the women of Africa, and women of African descent around the Atlantic, were wearing. In the period of the Atlantic consumer revolution, with globally circulating cloths and increasingly convergent fashions, reporting on African fashion had become a persistent trope of eighteenth century travel writing. Prints accompanied descriptions that explained the ways that African men and women used–or “misused”–fashion.

A big part of trying to describe the fashions of coastal Africa was an attempt to get on top of the market there, and a lot of recent and forthcoming research has been focused on the predominance of cloth in African trade (and it turns out there are great sources on this!).[2] Cloth was the biggest export to African ports in the era of the slave trade, and bringing the most fashionable cloths was vital to making a profit on one of these trading voyages. But it couldn’t be just any cloths. Traders reflected on what was fashionable (or not) in their letters back to the merchant companies that had sent them. Indian cottons made up an average of 65.6 percent of the foreign products exported from England to West Africa in the second half of the eighteenth century.[3] Ultimately, the demand for these cloths generated British investment in textile production and cut out the Indian producer. For the eighteenth century the demand was consistently for the huge range of “guinea cloths from India, which are highly prized by the Moors, and which they can accurately distinguish from those manufactured in Europe.”[4]

Agostino Brunias, Dominica, c. 1780

Actually, the connections went both ways: the most valuable non-slave imports by British merchants were materials used for the manufacture of dyes and ivory – two items used for British fashionable consumption.[5] But reflections on African fashions had a secondary, less directly commercial purpose as well. With West African demand shaping the import of cottons and silks from Asia, with calicos proliferating around the Atlantic World, reflecting on the use of these globalized goods in different cultures–colonial, native, enslaved–helped to identify and shape what was perceived to be “modern” about British or French fashions.

René Claude Geoffroy de Villeneuve, L’Afrique, ou histoire, moeurs, usages et coutumes des africains: le Sénégal (Paris, 1814), vol. 1, facing p. 69.

In the absence of (or disregard for) the sumptuary laws that had functioned to demarcate the boundaries between classes in the past (or, to quote Regina George again, “whatever, those rules aren’t real”), middle class colonial settlers as well as metropolitan non-elites needed guidance to help them shape their ideas about what set their own use of Indian cottons or Chinese silks apart from the other classes of people–particularly Africans and Native Americans–using those same goods. Reflecting on African fashion helped to define the “correct” way to use and approach global fashions.

So white audiences in the colonial Atlantic world were given glimpses of exotic fashion. Women in Senegal with elaborate headscarves and slaves carrying parasols; women in the Caribbean with rakishly angled hats; and the repetition of the description of women in elaborate skirts with their tops uncovered. Anna Maria joined in: “[The Queen] was dressed in the [Temne] country manner, but in a dignified stile, having several yards of striped taffety wrapped round her waist, which served as a petticoat; another piece of the same was carelessly thrown over her shoulders in form of a scarf; her head was decorated with two silk handkerchiefs; her ears with rich gold ear-rings, and her neck with gaudy necklaces; but she had neither shoes nor stockings on.”[6] For Falconbridge, and her readers, the point of this was to show the luxury as ridiculous–a trope that resonated with descriptions of enslaved “dandies” in the West Indies–and the juxtaposition with missing shoes or holey stockings highlighted that these people just didn’t get it, weren’t fashionable, and weren’t modern enough.

Robe à la Française, 1765-70, French, Metropolitan Museum of Art

But of course, (of course!), even with all of these attempts at fashionable superiority, the metropoles found their own fashions entangled with colonial dress. In Whydah, where the French slave trade was ongoing in the early eighteenth century, the style among the court was “a series of overlapping skirts of the finest silks, the inner skirt was draped down to the ankles, and the successive skirts were shorter and open in front in a manner reminiscent of the ‘open robe’ style,” which French traders speculated had inspired the same style in Paris.[7]

In other words, cultural appropriation of African fashion without acknowledgment has a long history.

[1] Anna Maria Falconbridge, Two Voyages to Sierra Leone (London, 1793), Letter III, May 13, 1791.

[2] For instance, Kazuo Kobayashi, “Indian Textiles and Gum Arabic in the Lower Senegal River,” African Economic History 45, 2 (2017), 27-53; Jody Benjamin, “The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce, and History in Western Africa, 1700-1850,” Doctoral Dissertation, Harvard University, 2016; Anne Ruderman, “Supplying the Slave Trade: How Europeans Met African Demand for European Manufactured Products, Commodities and Re-exports, 1670-1790,” Doctoral Dissertation, Yale University, 2016.

[3] Joseph Inikori, Africans and the Industrial Revolution (Cambridge, 2002), Appendix 9.5; Maxine Berg, “In Pursuit of Luxury,” Past and Present, 182 (2004), 110-112; David Richardson, ‘West African Consumption Patterns and Their Influence on the Eighteenth-Century English Slave Trade,’ in Henry A. Gemery and Jan S. Hogendorn, eds., The Uncommon Market: Essays in the Economic History of the Atlantic Slave Trade (New York, 1979), 312-315.

[4] Edited by Frederic Shoberl, Africa: containing a description of the manners and customs, with some historical particulars of the Moors of the Zahara, and of the Negro nations between the rivers Senegal and Gambia: illustrated with two maps, and forty-five coloured engravings. Vol. I. (London, 1821), 161-166; Colleen Kriger, Cloth in West African History (Lanham, MD, 2006); Beverly Lemire, Global Trade and the Transformation of Consumer Cultures: The Material World Remade, c. 1500-1820 (Cambridge, 2018); Jeremy Prestholdt, “On the Global Repercussions of East African Consumerism,” American Historical Review, 109, 3 (2004), 755-781; Giorgio Riello and Prasannan Parthasarathi, eds. The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton Textiles, 1200-1850 (Oxford, 2009).

[5] Jan Hogendorn and Henry Gemery, “The ‘Hidden Half’ of the Anglo-African Trade in the Eighteenth Century: The Significance of Marion Johnson’s Research,” Devid Henige and T.C. McCaskie, eds. West African Economic and Social History: Studies in Memory of Marion Johnson (Madison, 1990), 83.

[6] Anna Maria Falconbridge, Two Voyages, Letter III, Bance Island February 10, 1791.

[7] Robert Harms, The Diligent (New York, 2002), chapter 19, fn 6; Jean-Baptiste Labat, Voyage du Chevalier des Marchais en Guinee, Isles Voisines, et a Cayenne, fait en 1725, 1726 & 1727 (Amsterdam, 1731), vol. 2, 48.

I really like how your post works through the eyes of Anna Maria Falconbridge. I do wonder whether she was “discovering” the fashion and telling readers about it, or chronicling her attempt to wipe it.

I am curious, do you see more references to Afro-Muslim and Ottoman culture in the British fashion periodicals?

Pingback: This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History – Imperial & Global Forum