Materializing Race: An Unconference on Objects and Identity in #VastEarlyAmerica

August 24 and 25, 2020

1 PM EST both days (Zoom)

Proposals due by August 1, 2020

Organized by Cynthia Chin and Philippe Halbert

In a commitment to fostering nuanced interpretations of early American objects and meaningful dialogue on historical constructions of race and their legacies, we propose a virtual ‘unconference’ to share and discuss scholarship on the intersections of identity and material culture in #VastEarlyAmerica. This participant-driven, lightning round-style event will be held via Zoom, with two approximately two-hour afternoon sessions conducted in English. Energized by Dr. Karin Wulf’s call for broader, more inclusive histories of early America, we seek to promote a diverse cross-section of scholarship focused on North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean before 1830.

In a commitment to fostering nuanced interpretations of early American objects and meaningful dialogue on historical constructions of race and their legacies, we propose a virtual ‘unconference’ to share and discuss scholarship on the intersections of identity and material culture in #VastEarlyAmerica. This participant-driven, lightning round-style event will be held via Zoom, with two approximately two-hour afternoon sessions conducted in English. Energized by Dr. Karin Wulf’s call for broader, more inclusive histories of early America, we seek to promote a diverse cross-section of scholarship focused on North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean before 1830.

We welcome a variety of approaches and methodologies including historical, art historical, anthropological, archaeological, visual analysis, and experimental/experiential archaeological. Proposals should be object-focused and include a brief abstract (250 words with one relevant image) for a 10-15-minute presentation, along with a short CV of no more than 2 pages. Potential questions and themes for presentations might include:

- What is the next chapter in the discussion of race, ethnicity, identity, and early American material culture?

- What are potential methodological approaches and revisions/additions to existing material culture frameworks? How can #VastEarlyAmerica work to expand the traditional American material culture canon?

- What were some of the threads or outcomes of the 1619 Project dialogue (and other relevant publications/discussions) that relate/interact/tessellate with material culture studies? How can the 1619 Project and its surrounding narratives broaden the impact of material culture studies?

- Can the outcomes or discussions surrounding this dialogue engender new approaches/methodologies and discussions in material culture studies? How might it affect the way we as historians and curators interact with and publicly present objects? Does it present the ability to see “legacy” objects and historical figures/narratives differently as a result?

- Historians and material culture specialists as genealogists: how do our own personal family/ancestral narratives intersect with our study of early American history and material culture; the historian as biographer; the biographical object and the object biography

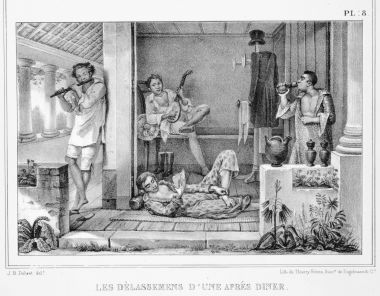

- Public history: new thoughts on old things, from the exhibition and display of objects in museum settings to historical and character interpretation, to include historic trades and foodways

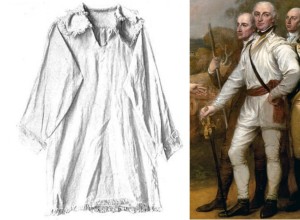

- Object Case Studies: New interpretations of early American objects related to race, ethnicity, and identity

- The influence of historical anniversaries and commemorations: Jamestown 2007, the New Orleans Tricentennial Commission, Plimoth Patuxet and Mayflower 400, the 500th anniversary of the Spanish invasion of Mexico in 2019 and the 2021 bicentennial of Mexican independence, etc.

This event is co-convened by Dr. Cynthia Chin (Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington) and Philippe Halbert (Yale History of Art). For more information, submission requirements, and audience registration details, please visit the Materializing Race website.

Today at The Junto, Philippe Halbert interviews Katherine Egner Gruber, who is Special Exhibition Curator at the

Today at The Junto, Philippe Halbert interviews Katherine Egner Gruber, who is Special Exhibition Curator at the

Working on material culture, my research has taken me to some interesting, if unexpected places. Last summer, it involved waiting outside Saint John’s Church in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, founded in 1732 as the Anglican Queen’s Chapel. I quickly ran inside to snap some pictures of a baptismal font between back-to-back Sunday services. The Saint John’s font is an impressive fixture, carved from marble in a Continental European baroque style. As a ritual object used in the sacrament of baptism, the font is hardly unusual, but its story is.

Working on material culture, my research has taken me to some interesting, if unexpected places. Last summer, it involved waiting outside Saint John’s Church in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, founded in 1732 as the Anglican Queen’s Chapel. I quickly ran inside to snap some pictures of a baptismal font between back-to-back Sunday services. The Saint John’s font is an impressive fixture, carved from marble in a Continental European baroque style. As a ritual object used in the sacrament of baptism, the font is hardly unusual, but its story is.