Today at The Junto we’re featuring an interview with Ann Little, an Associate Professor of History at Colorado State University, about her new biography, The Many Captivities of Esther Wheelwright. Little has previously authored Abraham in Arms: War and Gender in Colonial New England. She also writes regularly at her blog, Historiann: History and Sexual Politics, 1492 to Present.

Today at The Junto we’re featuring an interview with Ann Little, an Associate Professor of History at Colorado State University, about her new biography, The Many Captivities of Esther Wheelwright. Little has previously authored Abraham in Arms: War and Gender in Colonial New England. She also writes regularly at her blog, Historiann: History and Sexual Politics, 1492 to Present.

In The Many Captivities of Esther Wheelwright, Little chronicles the life of a New England girl, Esther Wheelwright, who was captured by the Wabanakis in 1703 when she was seven years old. After living with the Wabenakis for several years, Wheelwright entered an Ursuline convent in Quebec at age twelve. She lived the remainder of her life there, voluntarily becoming a nun and taking on several leadership positions in the convent, including that of Mother Superior, during old age.

JUNTO: You wrote in an interview with Theresa Kaminski that you first encountered Esther Wheelwright when writing your first book, Abraham in Arms. How did your understandings of eighteenth-century New England and Canada change as a result of writing a biography with a woman as its central figure?

ANN LITTLE: I don’t know if my understanding of the world I studied changed so much as I used Esther’s story to make an argument about how I think we should look at early North America as a place in which women’s leadership, work, and prayer were centrally important. Although allegedly we all know this already and we’re all enlightened non-sexist historians, I’m continually astonished by the numbers of early American women—even very well-known American women—are nearly invisible in the scholarly literature as subjects in their own right.

Have you ever read Bonnie Smith’s The Gender of History? If you haven’t, you should. She’s very pessimistic that history will ever be truly open to women historians or women as historical subjects because of its disciplinary roots. Our profession still remains overwhelmingly white and largely male. White men will write about nonwhite men, and in fact many white men have made fine careers writing and teaching about nonwhite men. But only a very few men of any race identify themselves as women’s historians, or put women at the center of their scholarship. So if women historians won’t write women’s history, who will? The answer is no one.

JUNTO: As you’ve noted, Esther Wheelwright is a challenging subject for a biography since there are so few sources concerning her early childhood, and only four surviving letters that she authored during her adulthood. Can you describe your research strategy for this book? How did you formulate a research plan?

LITTLE: I’m not so much a planner as a noodler. I just noodle along in a pile of sources—or with a few sources and get interested in one detail, which leads me to another detail, which might lead eventually to a story. Although by and large it was a disadvantage not to have a pile of primary sources about or by Esther, it was also a little bit of a relief because Quebec City is pretty far from Colorado, and I was only able to get away for (at most) two weeks of research at a time. I was able to conduct most of the traditional primary source research in four or five one- or two-week trips, and then figure out most of the rest of it from afar.

The richness of both the historical sources as well as the aural, visual, and material sources available to me via the internet were incredibly important in helping me bring Esther’s world to life, especially her life in Québec and inside the convent. I had never heard the Te Deum sung, so I looked up a YouTube video of it sung by some nuns. I also happened to stumble on a website that has a video of an older Ursuline dressing up a woman in an eighteenth-century habit. These helped her distant world feel a little more knowable to me across space and time.

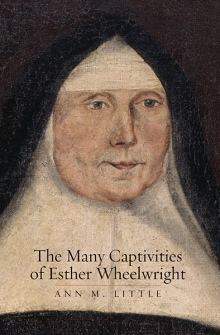

JUNTO: As someone who has spent many hours researching at the Massachusetts Historical Society, I was fascinated to learn that Esther Wheelwright’s self-commissioned portrait is hanging in the MHS seminar room! At what point in your research did you come across the painting, and how did this painting shape your understanding of Wheelwright?

JUNTO: As someone who has spent many hours researching at the Massachusetts Historical Society, I was fascinated to learn that Esther Wheelwright’s self-commissioned portrait is hanging in the MHS seminar room! At what point in your research did you come across the painting, and how did this painting shape your understanding of Wheelwright?

LITTLE: See what I mean? Hiding in plain sight!

I must have learned about the portrait from the amazing books by Emma Lewis Coleman New England Captives Carried to Canada Between 1677 and 1760 During the French and Indian Wars (Portland, ME: The Southworth Press, 1925; reprint, Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 1990) and C. Alice Baker, New England Captives Carried to Canada in two volumes, and True Stories of New England Captives Carried to Canada During the Old French and Indian Wars (Greenfield, Mass.: E. A. Hall & Co., 1897; reprint, Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 1990). They both feature photos of her portrait. (Incidentally, there’s a terrible copy of the painting in the Ursuline archives in Québec. Dreadful!)

The portrait was interpreted by Anne Bentley of the MHS one day in a fascinating private meeting. We peered over the portrait, which Anne had taken down for our study. It helped me understand more about the artistic accomplishments of the Ursulines, as Anne believes (and I agree) that it must have been painted by a fellow Ursuline. I write in chapters 4 and 6 about the Ursuline dedication to artistic production in all kinds of media—oil and watercolor painting, embroidery, gilding, and objects for the tourist trade that grows up rapidly during the British occupation.

JUNTO: I was impressed by your careful attention to material culture throughout The Many Captivities of Esther Wheelright. You have suggested that this focus on clothing, grooming, food, and material objects originated as a way for you to reconstruct Wheelwright’s life in the absence of other sources. But it seems that material culture is also an essential component of your arguments that “crossing political borders required cultural transformation” (90). How did you realize this was what you wanted to argue? And for those who have not yet read your book, can you describe an episode in Wheelwright’s life where this kind of cultural transformation is particularly apparent?

LITTLE: To answer your last question first: I think Esther’s cultural transformation is apparent in all of her moves—from Wells to Wabanakia, from Wabanakia to Québec, and from secular to religious life. This is how she not only survives, but thrives: she’s a kind of a Zelig, able to transform herself into the best Wabanaki girl, the most studious and devout French Canadian student, the most pious young nun.

Anyone paying attention can probably tell that I’m a lumper, not a splitter. I look for connections and common ground. When I thought about the story I wanted to tell about the northeastern borderlands, I saw in my mind’s eye the satellite that Bernard Bailyn evoked in a Braudellian flourish thirty years ago at the beginning of The Peopling of British North America: An Introduction. From maybe a little closer up—the height of a hot air balloon or a glider—I can see the similarities among French Canadian, Native American, and Anglo-American people in this region. Yes, they’re fighting constantly in this century, but they’re fighting because of their similarities, not their differences. They’re fighting over access and control of the same resources they all need, although they express their disagreements in the language of religious and cultural or even racial difference.

JUNTO: You contend that Esther Wheelwright was overlooked—even “doomed to obscurity”—by mainstream biographers because she was a woman whose life was marked by “transnationalism as a New England-born Catholic nun in New France” (226). What would you most like history professors to change about their teaching of early North American history in light of your book?

LITTLE: I want them to take women seriously and see them in their own research and teaching.

I’m not optimistic that anything is going to change any time soon. Take a look at Bonnie Smith’s book about the discipline of history systematically erasing women in history and as historians, then take a look at the books that win the Bancroft Prize, the National Book Awards, or really any list of prizewinning books outside of prizes specifically for women’s and gender history. Books with “Empire” in the title have been doing really well (#BecauseEmpire!) Biographies of male political and military leaders are still huge.

I know I chose poorly in writing about Esther Wheelwright. I chose to write about a little girl and a woman in a man’s world using the tools of a male-dominated discipline. I wrote about a Catholic in a language and historiography that privileges Protestant men and sees Catholics as superstitious, backwards, and anti-democratic. I wrote about a victim of warfare and captivity in a culture that privileges winning and winners at all costs. I wrote about someone who crossed borders and so doesn’t fit into any one national history or historiographical tradition. What was I thinking?

I was thinking that what we see as important and who we see as central to the story are choices, not self-evident truths. Nothing is inevitable. Everything is eminently evitable.

JUNTO: You have been blogging at Historiann since 2007, and you thank other academic bloggers in your acknowledgments. How did your experiences as a blogger shape your writing of The Many Captivities of Esther Wheelwright?

LITTLE: My fellow bloggers—most of them fellow mid-career women and a few men—were kind of an online support group for me. Many of us were struggling with the realization that tenure and promotion wasn’t a “promotion” in the sense that the rest of the world understands. All it means is that we didn’t get fired, so it’s up to us to find ways of making our work interesting.

Truly they are among the nicest, smartest, and most fun people I’ve met in the past decade. I really wish we could be an actual community rather than a virtual one.

JUNTO: What will you be working on next?

LITTLE: I’ve got a project in mind that combines fashion, material culture, and the history of the body in the period just after the American Revolution. Yes, I’m leapfrogging entirely over the American Revolution and moving full speed ahead into the Early Republic.

I don’t know how long I’ll last. Once you get close to 1800, the number of written, visual, and material sources alike just explodes. I don’t know if I can handle this surfeit of primary sources. Once you get comfortable with almost no primary sources, finding gobs and gobs and gigabytes of the stuff just laying around libraries and on the internet almost feels like a cheat.

Then again, I never ask questions that the sources just reveal to me. I always have to make it hard for myself, somehow.

Pingback: American biography in the age of the Human Stain | Historiann

Pingback: Canadian History Roundup – Week of November 6, 2016 | Unwritten Histories