The Watkinson Library at Trinity College has an impressive collection of manuscript music from the late eighteenth century. Thanks to a grant from the Bibliographical Society of America, I spent a few weeks in June on a research road trip in New England, and Trinity was my first stop. Although I was focusing on musical commonplace books and copybooks, at the suggestion of librarian Sally Dickinson I also worked with their collection of annotated hymnals. It was while perusing these volumes that I came across something I hadn’t seen before: a hymnal in which every reference to Britain had been crossed out and replaced with the word “America” or related terms (New England, Western States, United States, etc.) As the assiduous penman noted at the bottom of one page, the entire volume had been “translated to America.”

The Watkinson Library at Trinity College has an impressive collection of manuscript music from the late eighteenth century. Thanks to a grant from the Bibliographical Society of America, I spent a few weeks in June on a research road trip in New England, and Trinity was my first stop. Although I was focusing on musical commonplace books and copybooks, at the suggestion of librarian Sally Dickinson I also worked with their collection of annotated hymnals. It was while perusing these volumes that I came across something I hadn’t seen before: a hymnal in which every reference to Britain had been crossed out and replaced with the word “America” or related terms (New England, Western States, United States, etc.) As the assiduous penman noted at the bottom of one page, the entire volume had been “translated to America.”

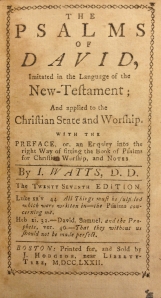

This volume, owned by one Alexander Gilles, is a copy of Isaac Watts’s Psalms of David Imitated in the Language of the New Testament.[1] Isaac Watts is a major figure in early American music history. His psalm paraphrases and hymns were sung to existing sacred tunes throughout the British colonies from the time they were published in London in the early 18th century (1707 for his Hymns and Spiritual Songs, 1719 for The Psalms of David). Decades after Watts died in 1748 his poetry exerted a strong influence on musical trends, inspiring the New England psalmodists who were America’s first homegrown composers to write more elaborate and demanding music in the 1770s and 1780s.

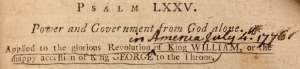

Yet while Watts’s poetry remained immensely popular during and after the American Revolution, his frequent references to “Northern Isles,” Britain, and kings were awkward for patriotic church-goers. In 1781 Newburyport printer John Mycall brought forth a new edition of Watts’s psalms from which all references to Britain had been scraped away by a committee of ministers. Four years later Joel Barlow released a “corrected and enlarged” edition of Watts’s psalms. Barlow had been commissioned by the General Association of Connecticut, which decided in June 1784 that they needed a version that omitted all references to Britain. In 1797 Timothy Dwight was asked to make a new revision by that same General Association. From 1781 to 1832 there were nine distinct revision projects that yielded at least 75 different editions or printings of Watts’s psalter.[2]

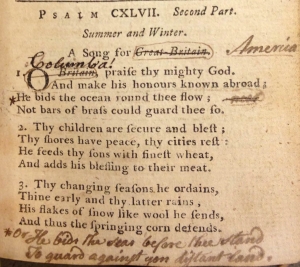

Alexander Gilles’s patriotic enthusiasm for revising Watts surpassed the official revised versions. His corrections are largely based on Mycall’s 1781 edition, but Gilles added further changes wherever he felt Mycall’s ministers failed to be thorough or go far enough. In more than one instance where Mycall’s edition left “islands” or “islands of the Northern sea” Gilles wrote “nations” or “Western lands.” Bound in with Gilles’s copy of the psalter are a 1772 Boston edition of Watts’s collection of Hymns and Spiritual Songs and a collection of hymn tunes by the Connecticut composer Andrew Law, and Gilles made adjustments to the language throughout those materials as well. Even the index is redacted.

Occasionally Gilles contributed entirely new poetic lines that highlighted his patriotic and anti-British sentiment. For example, in Psalm 147 he wrote corrected the subtitle and first line of lyrics based on the Mycall  edition, but also suggested changing the lines “He bids the ocean round thee flow / Not bars of brass could guard thee so” to “He bids the seas before thee stand / To guard against yon distant land.” It’s not hard to imagine that “yon distant land” is Britain, against which Gilles summoned God’s protection for the young nation.

edition, but also suggested changing the lines “He bids the ocean round thee flow / Not bars of brass could guard thee so” to “He bids the seas before thee stand / To guard against yon distant land.” It’s not hard to imagine that “yon distant land” is Britain, against which Gilles summoned God’s protection for the young nation.

The American Revolution and its aftermath receives plenty of attention here at The Junto, particularly with our coverage of The American Revolution Reborn conference in Philadelphia. Yet much remains to be said about the Revolution’s cultural reverberations, particularly when it comes to sacred music. Gilles’s annotations bespeak a man of diligence and creativity who committed to aligning his religious practice with his patriotism. One wonders if there are more annotated hymnals out there that display other attempts to reconcile sacred worship to patriotic politics. Moreover, further examination could reveal musical consequences from the changes to the psalms and hymns. Last week Roy Rogers suggested we need more sources on the intersection of Christianity and the Revolution. Gilles’s volume seems like a great example of such a source, leading me to wonder if we should be paying more attention to how sacred music responded to and was affected by the Revolution.

________________

[1] Isaac Watts, The Psalms of David: imitated in the language of the New-Testament (Boston: J. Hodgson, 1772). Watkinson Special BS1440 .W3 1772

[2] Louis F. Benson, “The American Revisions of Watts’s ‘Psalms’,” Journal of the Presbyterian Historical Society 2, no. 1 (1903): 18-34.

One very important area of intersection is Alexander Hamilton’s plan to found a new Christian movement before the duel with Burr.

What an amazing piece of evidence! What are you going to do this? Thanks for this piece.

It is neat, isn’t it? Although I stumbled upon this while looking for something else, I am fairly certain I will use to discuss post-Revolutionary musical transatlanticism in the book I’m working on.

Glenda, I saw this tweeted about by AASLH — any idea where Alexander Gilles was from? My spouse and kids are descended from an Alexander Gillies, who we think was from the New York area. It’d be a real kick if it’s the same guy. We have a 19thC Gillies diary from one of his grandsons about a trip he took back to Scotland which is a really neat document.

None of the annotations in hymnal indicate where Gilles was living, unfortunately. What’s more, the commenter below makes a good point about the name spelling–it could be Gilles or Gillet. Sounds like your spouse’s forebear led an interesting life!

Hey Glenda, Thanks for your sharing this excellent find. Do you happen to have a photo of the owner’s signature as it is inscribed in the book? I’m wondering if there is any possibility that this book belonged Alexander Gillet (1749-1826). Minister of the Congregational churches at Farmingbury (now Wolcott) and Torrington, Gillet was also a prolific early Connecticut composer. His song Farmington was widely reprinted in the decades immediately following the Revolutionary War, along with several other of his tunes. Gillet began his ministry in 1773, and began to publish tunes (many of which were set to texts by Watts) in 1779. Additional infomoration about Gillet is available at:

http://books.google.com/books?id=LYMAAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA68&dq=alexander+gillet&hl=en&sa=X&ei=_-cAUryXKpCw8QTC9YCwAw&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=alexander%20gillet&f=false

and:

http://books.google.com/books?id=nsTYAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA70&dq=alexander+gillet&hl=en&sa=X&ei=_-cAUryXKpCw8QTC9YCwAw&ved=0CEEQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=alexander%20gillet&f=false

Anyway, please let me know if think this book might have belonged to him.

Thanks again for a great post!

A.

I do have a photo of the signature, and I think you may be right! I’m no handwriting expert, but the “t” is slightly bowed (like a cursive “s”), and comparing it to other instances I think this was how he occasionally wrote the letter.

If the annotator was Gillet, then this story becomes even richer and more intriguing. I am very grateful to you for making the connection! Is this something you are interested in for your own work?

Alexander Gillet was the first pastor of Wolcott Congregational Church. http://www0.cpdl.org/wiki/index.php/Alexandria_(Alexander_Gillet)