The wait is over. For the next few weeks, over-specialized nerds across the country will huddle over their desks, pencils in hand, brows furrowed, debating matchups and predicting winners. Lines will be drawn. Disagreements will be had. Relationships may be strained. The historiographical world as we know it may never be the same again.

The wait is over. For the next few weeks, over-specialized nerds across the country will huddle over their desks, pencils in hand, brows furrowed, debating matchups and predicting winners. Lines will be drawn. Disagreements will be had. Relationships may be strained. The historiographical world as we know it may never be the same again.

That’s right, the Junto March Madness Bracket has finally arrived!

This year, the bracket is focused on primary sources. Specifically, primary sources that you would use in the classroom. These could be larger edited collections, single letters, or even an engraving. This is meant to introduce readers and teachers to new pedagogical tools designed to unlock the study of the past.

A few rules guided how we constructed the brackets based on your wonderful nominations:

- We tried to break up the brackets into vaguely thematic topics. As you’ll see, some are a real stretch. However, given the nature of this year’s tournament, it was hard to find a common theme, and so we ended up being creative. Don’t judge us too harshly.

- Seeds 1-8 in each bracket were mostly decided based on our anticipation of how much support those documents will receive, though obviously this took a lot of guesswork.

- Seeds 9-16 were not based on how we felt those documents would do, but were chosen based on if they created an interesting first-round matchup that would spark discussion.

- As a reminder that we give out every year: this exercise is meant to be fun. There is no way to truly determine what is the “best” document to use in the classroom. If any document doesn’t do as well as you expect, or if any subfields or subtopics seem underrepresented, it is based on readership nomination and voting. Most especially, the purpose of this year’s tournament is to use a fun venue (March Madness) to introduce teachers to a broad array of documents that they may want to consider using in the classroom.

Related to that last point, we hope that these brackets will cause lots of discussion. Why do you think a particular document deserves to go far in the tournament? How have you used that document in the past? How do you propose to use it in the future? Your campaigning is not only meant to help a document “win,” but to provide pedagogical tools to your digital colleagues.

On Monday, when voting for Round 1 begins, we will feature paragraphs in defense of various documents that are written by Juntoists. If you would like to write a paragraph to be included as well, please email it to me at benjamin.e.park AT gmail.com. Or, you are also strongly encouraged to add your commentary in the comments below.

The hashtag for this year’s tournament is #JMM15. We received a lot of digital chatter last year, and hope it continues again.

Without further ado, behold the brackets!

Junto March Madness 2015 Schedule

- March 2nd-4th: Reader Nominations

- March 6th: Announce Brackets

- March 9th & 11th: First Round Voting

- March 16th & 18th: Second Round Voting

- March 23rd: Round of 16

- March 26th: Quarterfinals

- March 30th: Semifinals

- April 6th: Final

Brackets

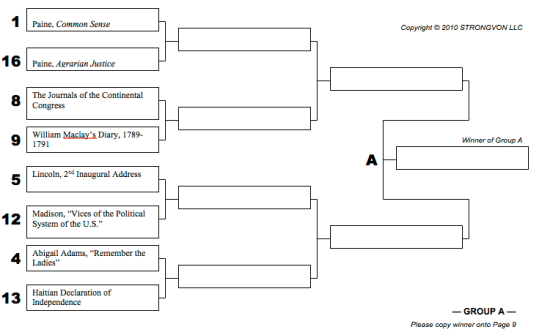

BRACKET ONE: Political History

1. Thomas Paine, Common Sense vs. 16. Thomas Paine, Agrarian Justice

2. The Declaration of Independence vs. 15. John Jay, “An Address to the People of the State of New-York” (1788)

3. Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America vs. 14. William Manning, “The Key of Libberty”

4. Abigail Adams’s “Remember the Ladies” Letter vs. 13. Dessalines, Hatian Declaration of Independence, January 1, 1804

5. Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address vs. 12. James Madison, “Vices of the Political System of the United States”

6. Alexander Hamilton, “First Report on the Public Credit” vs. 11. Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

7. The Constitution vs. 10. Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison, The Federalist

8. The Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 vs. 9. William Maclay’s Diary, 1789-1791

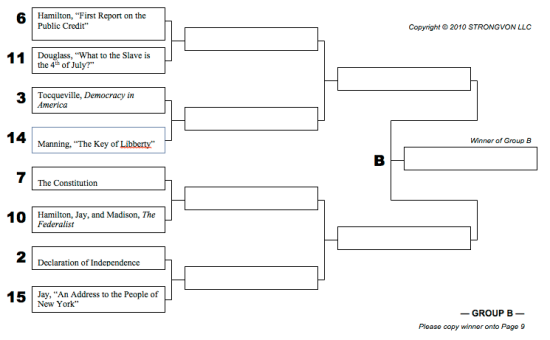

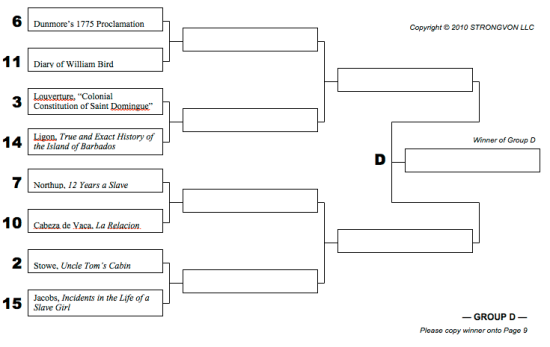

BRACKET TWO: Slavery, Captivity, and Bonded Labor

1. Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass vs. 16. David George, “An Account of the Life of Mr. David George”

2. Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin vs. 15. Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

3. Toussaint Louverture, “Colonial Constitution of Saint Domingue” vs. 14. Richard Ligon, True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados

4. David Walker, Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World vs. 13. The Diary of Philip Vickers Fithian

5. Mary Rowlandson, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God vs. 12. James Axtell, ed., The Deposition of Robert Roule

6. Lord Dunmore’s 1775 Proclamation vs. 11. Diary of William Bird of VA

7. Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slaves vs. 10. Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, La Relación

8. Richard Freethorn’s 1623 Letter vs. 9. William Moraley, The Infortunate: The Voyage and Adventures of William Moraley

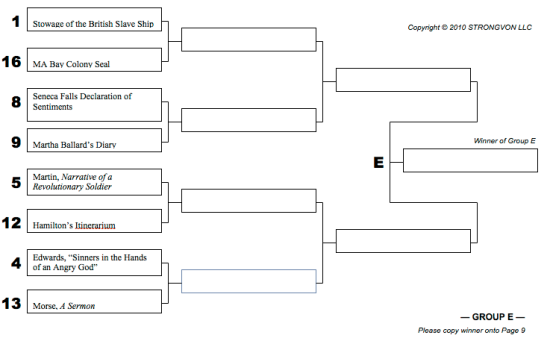

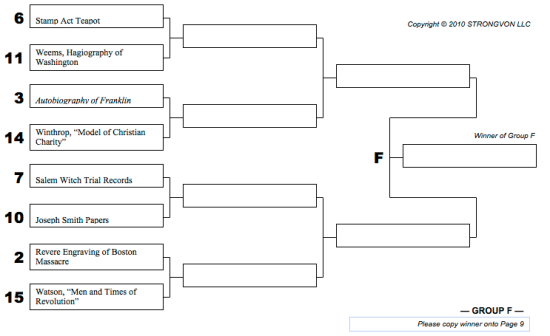

BRACKET THREE: U.S. History Superstars

1. Stowage of the British Slave Ship Brookes Under the Reguladed Slave Trade Act of 1788 vs. 16. Massachusetts Bay Colony Seal of 1629

2. Paul Revere’s Engraving of the Boston Massacre vs. 15. Elkanah Watson, “Men and Times of Revolution: Memoires of Elkanah Watson”

3. Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin vs. 14. John Winthrop, “A Model of Christian Charity”

4. Jonathan Edwards, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” vs. 13. Jedidiah Morse, A Sermon, Delivered at the North Church in Boston

5. Joseph Plumb Martin, A Narrative of a Revolutionary Soldier vs. 12. Dr. Alexander Hamilton’s Itinerarium

6. The “Stamp Act Repeal’d” Teapot vs. 11. Weems, A History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits of General George Washington

7. The Salem Witch Trials Records vs. 10. The Joseph Smith Papers

8. Declaration of Sentiments from the Seneca Falls Convention vs. 9. Martha Ballard’s Diary

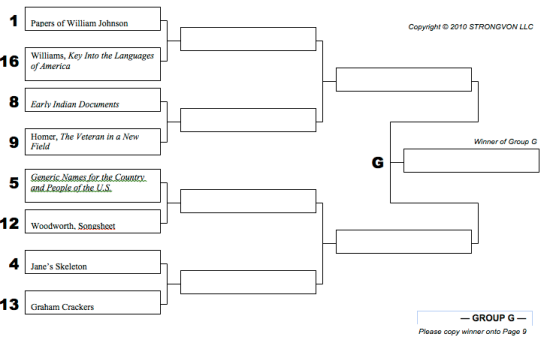

BRACKET FOUR: Not Rush Limbaugh’s American History

1. The Papers of Sir WIlliam Johnson vs. 16. Roger WIlliams, Key Into the Languages of America

2. 1721 Catawba Map vs. 15. Peter L’Enfant’s Plan for Washington City (1791)

3. Thomas Hariot, A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia vs. 14. Mathew Carey, “Advice and Suggestions to Increase the Comforts of Persons in Humble Circumstances”

4. Jane’s Skeleton (Jamestown) vs. 13. Graham Crackers

5. Generic Names for the Country and People of the United States (1803) vs. 12. Samuel Woodworth, Songsheet for “Hunters of Kentucky”

6. Barry O’Connell, ed., A Son of the Forest and Other Writings by William Apess, a Pequot (UMass, 1992) vs. 11. Benjamin Rush, “Moral and Physical Thermometer”

7. Miguel Leon-Portilla, ed., The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico (Beacon Press, 2006) vs. 10. Rafter, Memoirs of Gregor M’Gregor

8. Alden T. Vaughan, ed., Early American Indian Documents, Treaties, and Laws, 1607-1789 vs. 9. Winslow Homer, The Veteran in a New Field

_________________________________________________

You can download a .doc version of the bracket here. Images are below.

Let the games begin!

#15 Elkanah Watson: U.S. History Superstar!!!!! Albany and New England represent and we don’t even have to talk about the great waterspout/gutter controversy of 1788/89. Seriously though, this is an amazing, but little known source.

Are we allowed to campaign in the comments? Like can I provide this link to the book:https://archive.org/details/mentimesofrevolu00wat and recommend pages 177-178 if you want to learn how King George III’s entered Parliament to recognize American Independence?

Or pages 34-66 if you want to know more about how this New Englander viewed and understood the customs of the southern colonies in 1776?

Is this type of campaigning for your source allowed?

Liz: YES! Anything that gets people talking about lesser-known sources

You do realize that the Vaughan’s _Early American Indian Documents_ includes 20 huge volumes?

I realized this morning that if there’s a flaw to this bracket, it’s the absence of exploding steamboats in the antebellum era. Students *love* exploding steamboats.

I think professors also enjoy exploding steamboats.

I am particularly intrigued by the Thomas Paine vs. Thomas Paine match up in the top bracket. Can Paine upset Paine? That is the question.

Well we know that whoever loses will be in a world of … hurt.

No Letters of John Adams? Not even the Adams Family collection? Thoughts on Government should have been on this somewhere.

Nice bracket though.

I tried to nominate some Adams stuff. Major, disappointing omission.

Indeed, there aren’t many examples of presidential prose here… although I can’t say I’m surprised, considering the scholarly trend these days. What about Washington’s Farewell Address, Jefferson’s First Inaugural, or Jackson’s Bank Veto? Still, a highly interesting and creative bracket overall!

Interesting point.

Perhaps a fifth bracket is needed that IS Rush Limbaugh’s American History. Or maybe next year we limit entries to items in the Oklahoma AP replacement course.

I’m not sure the snark is merited in this case, though it is certainly representative of the general disdain for presidential history among academic historians today. Should our students read Mary Rowlandson but NOT the text of Jefferson’s Inaugural? Then they’ll be even less prepared to deal with the Rush Limbaugh’s of the world.

In other words, I wasn’t suggesting we exclude any of the entries above (including Rowlandson), only that the bracket fails to embrace certain documents which, believe it or not, were FAR more influential in their own time than many of the current entries. Presidential addresses may seem obvious or hackneyed to us, but guess what: your students probably don’t know anything about them. That ignorance won’t serve them well.

Sorry Robert. Snark not intended. At least not to the degree you may have assumed. I do genuinely think it is interesting that the nominations went in this direction. And I agree with you that some of the sources you mention are vital to our understanding of the past.

As you suggest, their place as well known and well-trodden foundational documents likely counted against them in this particular format as folks sought to nominate the unique and fascinating sources that they love to engage with. However, I would bet that many if not most of the folks who nominated and seconded sources for consideration also grapple with these texts and ideas in their classrooms.

My apologies too, Adam. I think you’re right about the selective nature of this format, and I should only blame myself for not having nominated other sources during the appointed window. Your comment probably just hit a nerve — namely, my growing recognition (as a grad student at a large public university) that too many of our students never grapple with some of the foundational documents I mentioned. Maybe they once studied them in High School, but nowadays young people arrive at college only to bypass Washington’s Farewell in favor of Abigail Adams’s “Remember the Ladies.” Both sources may be equally important, but without the former, well, our students’ sense of history will be just as skewed as it was for all those years when nobody remembered the ladies!

On a final note, I genuinely wish I had nominated Jackson’s Bank Veto. Despite the bigoted views of its author, the veto message was then, and is now, an inspired rallying cry for the rights of working-class people everywhere — or as Jackson called them, the “humble members of society.” I have found that students connect with his populist appeal, and when the veto is paired with Jackson’s views on Indian Removal, the teaching opportunities are virtually boundless.

The problem is time. I would love to use more primary sources in my American History to 1865 class, but I just do not have the time. In fact, class time is limited to less than 45 total hours. The only way I can get some of the sources in the class is by flipping it and even then you can’t spend the time you want on them.

The survey courses are just not able to go deep enough into eras to use too many primary sources. If you do, then you run the risk of giving them something without allowing the time to develop the source in its context. Therefore you have to be selective and no matter what happens, you will always end up leaving out valuable sources. It really becomes a matter of useful selection.

I agree completely with Robert Richard, particularly about the danger of resigning key aspects of our political past to know-nothing f***wits such as Rush Limbaugh.

In the spirit of friendly competition, here are some reasons why the 1721 Catawba map (http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/15/CatawbaMap1721.jpg) deserves a spot in the final four. (I’ll give up on my other two nominations, matched against Alexis de Tocqueville and Jonathan Edwards)

Max Edelson interview with the “Backstory” radio show describes the map’s importance: “In some ways it’s not an inaccurate representation of space, it just privileges the details that mattered to the Catawbas. And what mattered here was how people were in relation to one another, not how much physical space separated them.” https://soundcloud.com/backstory/backstory-with-the-american-24

Likewise, Alan Taylor’s essay in the recent collection American History Now begins with a lengthy description of the map as a structuring metaphor for how scholars are beginning to approach the study of colonial North America: “In this map, Indians hold the center, while the colonists remain marginal… The self-assurance of the map jars our conventional assumptions about Indians, for we usually narrate colonial history as a relentless and irresistible British drive to dominate and dispossess native peoples… We do not expect to find them acting as the self-confident teachers of colonists cast as rather obtuse, but redeemable, students. The map offers an alternative vision of coexistence on native terms.”

In my view, it’s a truly powerful teaching resource. It’s rare for one image to lend itself to so many fruitful discussion possibilities: the “new worlds for all” paradigm, the existence of Native geographies (as Juliana Barr’s 2011 WMQ article helps us think about), issues of diplomacy and commerce, and more.

Since it was my nominee, I’ll say a few things about Peter Charles L’Enfant’s plan for the national capital. http://www.loc.gov/item/88694195/

Really broadly, the plan provides a nice introduction to the ideas of urban design and the built environment. For most students, even those at institutions with a comprehensive liberal arts core, this may be the only moment in their entire education that they stop to consider the notion that the form of the human-created world they inhabit both reflects and affects the lived experience of a people. After we discuss the choices made by L’Enfant, I always try to get them to think a bit about the design and development choices made in their own towns.

For early American History more specifically, I bring up the plan when discussing the Federalists’ (and particularly George Washington’s) vision for the new nation. The city map and the details L’Enfant provided on the plan (the text on the left side of the image) lay out a grand vision for a large and dynamic national metropolis designed to foster nationalism and to bring the various states and sections together.

For example, he proposed assignment of fifteen city squares, many located at the intersections of the city’s grand avenues, to the individual states. Each would then improve the square and provide symbolic republican ornamentation. These areas were designed to welcome citizens of the infant republic and allow them to consider the lessons of the Revolution reflected in the “Statues, Columns, [and] Obelisks” erected by the state and federal governments.

L’Enfant designed the city’s grand avenues not only to provide line of sight views of the main government buildings, but also to be an impressive and imposing feature in their own right. On the plan, each of the large diagonal avenues that crisscross the grid of streets in the city avenue stretched 160 feet wide.

The bold nature of the whole plan is made more impressive by the fact that, beyond Georgetown, the land depicted on the map was merely farms, fields, swamps, and woodlands when the plan was drawn. In 1789 L’Enfant wrote that, “No nation had ever before the opportunity offered them of deliberately deciding upon the spot where their Capital City should be fixed, or of combining every necessary consideration in the choice of situation; and although the means now within the power of the Country are not such as to pursue the design to any great extent, it will be obvious that the plan should be drawn on such a scale as to leave room for that aggrandizement and embellishment which the increase of the wealth of the Nation will permit it to pursue to any period, however remote.”

L’Enfant knew that, in 1791, the infant republic lacked the resources and population to create such a grand metropolis. Nonetheless, he proposed a city covering nearly ten square miles of land at a time when Philadelphia’s settled population covered a little over one square mile. (If my perches to miles calculations and this 1794 map of the latter city are accurate http://libwww.freelibrary.org/diglib/ecw.cfm?ItemID=MHARAA00001.) However, L’Enfant allowed his faith in the American experiment to guide his vision for the capital.

This source really shines as an example of that faith in the new American republic and the vision for the nation held by people like L’Enfant and President Washington.

Pingback: Junto March Madness: Round 1, Day 1 Voting « The Junto

Pingback: Junto March Madness: Round 1, Day 2 Voting (Brackets 3 and 4) « The Junto

Pingback: Junto March Madness: Final Four Voting « The Junto

Pingback: Junto March Madness: Final Four Results AND Championship Voting « The Junto