This Colonial Couture post is by guest contributor Kimberly Alexander, adjunct professor of history at the University of New Hamphire, Durham. Her forthcoming book is Georgian Shoe Stories from Early America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017), and she is currently the Andrew Oliver Research Fellow at the Massachusetts Historical Society.* Follow her @SilkDamask.

John Leverett’s Buff Coat, ca. 1640

For scholars who are deeply interested in the connections between material culture and social history, textiles can be imagined as significant documents. Contextualizing objects through print culture, and exploring print through materials, allows us to texture the past and to weave “fashion stories” that complicate conventional histories. A favorite site for this work is the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS), home not only to one of the country’s most significant collections of letters, manuscripts and decorative arts, but also houses an important collection of textiles, clothing, and shoes, spanning the broad sweep of Massachusetts history. As the Andrew Oliver Research Fellow for 2016-2017, I have had the special opportunity to investigate pre-1750s textiles within the Society’s collection. Here, the lure of seeing objects, many of which had not been viewed for over 40 years, is particularly exciting.

The role that families have played in preserving parts of their history through the reuse and retention of key garments and textiles receives full expression in the collection of the MHS—the Alden, Adams, Byles, Franklin, Dawes, Hancock, Leverett, Stoughton and Oliver families among them. Identifying families who purchased (predominately British goods) and then handed down artifacts to succeeding generations, suggests patterns of consumption and the importance of family histories within the New England merchant elite. Further, the survival of groups of textiles with certain families renders it possible to trace patterns in Anglicization before and just after the ‘consumer revolution.’[1] The ongoing process of integrating family textiles with letters, copy and account books, and correspondence adds depth and dimension to MHS existing paper-based holdings. Two items connected to John and Hannah Leverett illustrate how fashion stories enrich our understanding of the past.

The History Told by Governor John Leverett’s Buff Coat

Governor John Leverett made several return visits to England after emigrating to Boston in 1633, seeing to business, political and military affairs. He had access to global markets and naturally would have purchased the latest luxury goods for himself and his family. During an extended visit around 1644, he served under Oliver Cromwell during the English Civil War (1642-1651) and apparently held military command in the regiment of Thomas Rainsborough, serving with distinction.[2] The MHS holds Leverett’s circa 1640 buff (from the term buffalo or ox) coat, a type of heavy and very thick leather jacket or coat used in battle.[3] The maker is unknown.

Detail, John Leverett’s Buff Coat

Leverett’s buff coat reveals something about his service for the Roundhead cause. This was a costly, but necessary garment and Leverett’s buff displays signs of hard use and distress from battle including scrapes, blood, and damage resulting from being pierced with a sharp weapon. Once adorned with silver fastenings, the coat features ornamental scalloped cutting along the cuffs and at elbow cut-outs, so a valuable silk could be seen underneath (a similar period technique to slashing), which added expense and was common to the period.[4] As noted in a letter from John Tuberville to his father-in-law in 1640: “For your buff-coat I have looked after, and the price they are exceedingly dear, not a good one to be gotten under 10 pounds, a very poor one for five or six pounds.”

Other forms of material culture complement Leverett’s coat and the print record. A painting of Leverett (attributed to Peter Lely) in his buff coat is extant at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem. The painting depicts him in this coat with his sword and family crest behind him. Leverett’s coat is of several high-waisted panels or skirts, and he has a belt round his waist (there is one belt loop remaining on the buff coat with visual evidence of another). Several such coats survive in North American and British collections, including a similar examples held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the York Castle Museum (UK), which houses the buff coat of Sir Thomas Fairfax.

The Family Story Told by Lady Hannah Leverett’s Quilted Petticoat

How can we write history when we do not have the original object? This is the dilemma posed by Hannah Leverett’s quilted petticoat. The actual garment unfortunately no longer survives, despite the fact that generations of Leveretts passed it down from generation to generation. It was ultimately destroyed in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. Fortunately, the wife of one of Leverett’s descendants recognized its importance and had created what is known as a pricking of the petticoat stitching pattern, from which a tracing of the entire petticoat was made.

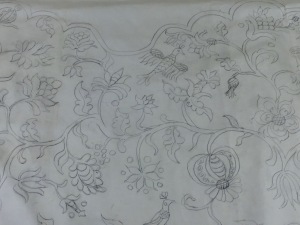

Detail, Petticoat Quilting Pattern, with flowers, blossoms, and birds

The quilted petticoat, identified as a farthingale pattern in the collections records, most likely was worn between the 1630s and 1640s by Hannah Hudson Leverett (1621-1643). The daughter of Ralph Hudson and Mary Hudson, Hannah was born in 1621 in Kingston-on-Hull, Yorkshire, England. She emigrated to Massachusetts as a teenager aboard the Susan and Ellen in 1635.[5] Four years later, in 1639 she married merchant John Leverett (1616-1679), who would become a governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Family notes share that this valuable item was Dutch, and was a gift to her from her husband, a reminder of the vibrancy of the Atlantic economy.

Gifts of luxury textiles were not uncommon in the seventeenth and eighteenth century; indeed, in 1782 John Adams, presented Abigail with the gift of a “saucy” scarlet cloth manufactured in Holland:

“I have Sent you an whole Piece of most excellent and beautiful Scarlet Cloth–it is very Saucy. 9 florins almost a Guinea a Dutch ell, much less than an English Yard. I have sent some blue too very good. Give your Boys a suit of Cloths if you will or keep enough for it some years hence and yourself and Daughter a Ridinghood in honour of the Manufactures of Haerlem. The Scarlet is ‘croise’ as they call it. You never saw such a Cloth.”[6]

During their brief marriage, Hannah and John had three children: Hudson John Leverett (1640-1694), John Leverett (1641-1650), and Hannah Leverett (1643-1651). Hannah died at the age of 22 in April 1643 at Boston, probably from complications following her daughter’s birth. Hudson was the only child to reach maturity and it is through his descendants that the petticoat was handed down, eventually reaching the donor to the MHS, Alice (Scott) Knight Smith. It is a tantalizing reminder of pieces lost despite efforts of several generations of family. The original farthingale came to the donor on the distaff (or female) side of her first husband’s family. The pattern was first pricked onto paper by the donor in 1896. After the original farthingale burned, she transferred the pattern to a piece of muslin, given to the MHS in December 1953.

Silver Tissue Dress, ca. 1660

Family records surrounding the petticoat are very specific and include not only the pricking, but also a verbal description “of a blue grosgrain silk quilted in white silk thread and has the effect of pale silver tissue.” [7] It must have been an elegant and high-style garment. Having the “effect of pale silver tissue” identifies it as a particularly expensive piece—perhaps it was even worn for her wedding.

The use of the term “farthingale” well into the 17th century brings up questions regarding the understanding of the term by the family or an early cataloger.[8] A farthingale has associations with women’s garments in the later sixteenth century and, frequently, court presentation raiment. Similar examples of the delicate shimmering “tissue” may be seen in the oil portraits of Dutch-born, English court painter, Peter Lely (1618-1680), such as that of Hannah Bulwer or his Lady in Blue.[9] The so-called silver tissue dress from the Fashion Museum at Bath (c. 1660) is a rare 17th century survival and provides an excellent comparison to the manner of making this ultra fine and expensive textile as well as a visual reference for Hannah’s petticoat.

An English buff coat and a Dutch silk quilted petticoat would not have been out of place among the 17th century merchant elite of Boston. Indeed, such fashionable luxury items would have confirmed the couple’s status as those “of the quality.” In this British-American city, one could easily find the trappings of far distant markets.

Many examples survive of textiles and clothing that augment and reinforce family narratives. The very nature of the decision to retain a piece of clothing or a textile fragment (whether by a family or an institution) represents a choice on the part of the owner or owners. It may be surprising for some to learn that examples of the most expensive, high-end luxury goods of the 17th-century Atlantic world exist in collections such as those at Colonial Williamsburg, Winterthur Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Peabody Essex Museum, among many others.

*The author thanks Curator Anne Bentley & the staff of the MHS for their ongoing and thoughtful assistance.

_________________

[1] John Murrin, “Anglicizing an American Colony: The Transformation of Provincial Massachusetts,” diss. Yale, 1966; Ignacio Gallup-Diaz, et al., Anglicizing America: Empire, Revolution, Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015); T.H. Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004);

[2] For John Leverett’s letters, see: https://www.masshist.org/features/saltonstall/john-leverett

[3] The buff leather coat worn by Governor John Leverett (1616-1679) was given to the Society by John Leverett on March 21, 1803. For information of the history and construction of buff coats, see Mary Doering “Buff Coats” in Clothing and Fashion in American History: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia, Volume 1: Pre-Colonial Times through the American Revolution, ed. Mary Doering. San Francisco: ABC-CLIO/Greenwood, 2015, 42-43.

[4] For an example of a contemporary reproduction buff coat, see: http://www.sarahjuniper.co.uk/17c.html

[5] Hannah Hudson emigrated on the Susan and Ellen in 1635. For a passenger list, see: https://www.geni.com/projects/Great-Migration-Passengers-of-the-Susan-and-Ellen-1635/people/15966

[6] John Adams to Abigail Adams, 12 October 1782, Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive, Massachusetts Historical Society (http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams). Original manuscript: Adams, John. Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 12 October 1782. 3 pages. Original manuscript from the Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[7] MHS Collections Files, Accession #0164

[8] The great farthingale associated with the Elizabethan era, remained in fashion into the first few decades of the 17th century, mostly for court functions, after which the fashion died out. Who first used the term ‘farthingale’? Was it an earlier ancestor or a cataloger? Did they mean a ‘roll farthingale’ or another modification?

[9] For Peter Lely, see: http://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/list.php?m=a&s=tu&aid=2944

Terrific, can’t wait for the book to come out– thanks!

Pingback: Canadian History Roundup – Week of February 5, 2017 | Unwritten Histories

Thanks for sharing news of our #ColonialCouture roundtable, good readers!

If you study material culture, the deadline is almost here (1 MARCH) to apply for the Andrew Oliver research fellowship at the Massachusetts Historical Society. New scholarship welcome!

Get details here: http://www.masshist.org/research/fellowships/short-term

Pingback: Of Records and Rituals: Native Americans and the Textile Trade « The Junto

Can it be determined from John Leverett’s coats measurements how tall the governor was?

Pingback: A Long Day's Journey for Madam Knight | Society for US Intellectual History