This is the fifth and final post in The Junto’s roundtable on the Black Atlantic. The first was by Marley-Vincent Lindsey, the second was by Mark J. Dixon, the third was by Kristin O’Brassill-Kulfan, and the fourth was by D. S. Battistoli. Ryan Reft is a Historian of Modern America in the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress. He also writes for KCET in Los Angeles. His work has appeared in journals such as Souls, Southern California Quarterly, California History, and the Journal of Urban History, and the anthologies, Barack Obama and African American Empowerment and Asian American Sporting Culture.

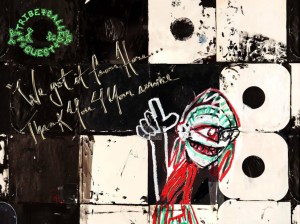

When A Tribe Called Quest (ATCQ) dropped its final album We Got It From Here . . . Thanks 4 Your Service, for a generation of Americans who attended college in the 1990s, it hearkened back to Clintonian multiculturalism, Afrocentric rap groups of the Native Tongues movement (De La Soul, Black Sheep, Jungle Brothers, and ATCQ), and hazy apartment parties carried by the rhythms of hip hop and its variants. Though a thoroughly modern creation, hip hop like that of ATCQ results from the accretion of political, social, and cultural forms arising from the Black Atlantic; the transnational culture created by the intersection of European empires, slavery, and colonization from the 1600s forward. Birthed and nurtured by the Black Atlantic, hip hop is our countermemory to American exceptionalism and chauvinistic nationalism.

When A Tribe Called Quest (ATCQ) dropped its final album We Got It From Here . . . Thanks 4 Your Service, for a generation of Americans who attended college in the 1990s, it hearkened back to Clintonian multiculturalism, Afrocentric rap groups of the Native Tongues movement (De La Soul, Black Sheep, Jungle Brothers, and ATCQ), and hazy apartment parties carried by the rhythms of hip hop and its variants. Though a thoroughly modern creation, hip hop like that of ATCQ results from the accretion of political, social, and cultural forms arising from the Black Atlantic; the transnational culture created by the intersection of European empires, slavery, and colonization from the 1600s forward. Birthed and nurtured by the Black Atlantic, hip hop is our countermemory to American exceptionalism and chauvinistic nationalism.

Admittedly, the death of Phife Dawg aka the Trini Gladiator aka Malik Taylor adds a healthy dose of sadness to an album about soulful perseverance in the face of hostility. “There ain’t no space program for” black people, Q-Tip raps in the chorus on the opening track, “you stuck here.” On its second song, “We the people,” he sarcastically tells listeners, “All you black folks, you must go / All you Mexicans, You must go / All you poor people, you must go / Muslims and gays, boy, we hate your ways / All you bad folks, you must go.” Throughout, Q-Tip, Jarobi, and Phife (Ali Shaheed Muhammad does not appear on the album) provide a sense of steely reserve that, if not exactly revolutionary, stands as a clear statement of resistance against the anti-globalization, anti-political correctness, anti-establishment wave of political rhetoric that seems to have gripped the nation and perhaps the larger West.

In this way and others, ATCQ represents the culmination of two centuries of the cultural Black Atlantic: an afrocentric, arguably bohemian, rap group with members that can trace their ethnic ties back to the Caribbean. “I get the Roti and the Soursop . . . ” Phife rapped on “Ham and Eggs” from the group’s first album; one of countless references to his Trinidadian ethnic background. Moreover, We Got It From Here is awash in Caribbean rhythms and reggae/dancehall flows.

Birthed by European imperialism, forced labor, namely slavery, and the rise of oceanic travel, the Black Atlantic brought indigenous peoples, Africans, and Europeans into daily if unequal contact. Though its creation might have been driven by the forces of the West, the culture of the Black Atlantic existed outside of western national borders as its central participants, were often marginalized by and resistant against the very powers that led to its emergence. White slave owners and colonial governors might have feared the revolutionary ideas carried and shared along Black Atlantic routes of exchange, but they hardly understood them or the means by which such notions were transmitted.

At the same time that ATCQ came to prominence in the 1990s, historians made what is called the “transnational turn”: a move away from American exceptionalism towards a reevaluation of the nation’s cultural, political, and economic history in the frame of the larger international world. Due in part to this historiographical shift, the history of the Atlantic world, the study of intersections between Europe, the Americas, and Africa, took on an increased importance. Further, the Black Atlantic within the larger Atlantic surfaced as a popular and pervasive subject. Emerging from the combined scholarly interests in British Imperialism, New World slavery, and African agency, the Black Atlantic suggested a fascinating means to rethink identity and cultural and political revolution. In 1993, Paul Gilroy published the seminal classic The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, arguably the quintessential work of the Birmingham school of cultural studies.[1] Transnational structures created the Black Atlantic, noted Gilroy, so its resonance must be considered in a similar vein. “I want to develop the suggestion that cultural historians could take the Atlantic as one single, complex unit of analysis in their discussions of the modern world,” Gilroy wrote, “and use it to produce an explicitly transnational and intercultural perspective.”[2]

The power of Gilroy’s formulation spread across the field. As Glen Mimura noted in 2009, the Black Atlantic in “its diasporic geography, cultural forms, and philosophical ideas [functions] as a ‘countermemory’ to the legacy of European Enlightenment thought.”[3] Black historians, scholars like Robin D. G. Kelley have argued, proved particularly adept at grasping transnational history. Often relegated to second class citizenship within their own nations and experienced in resisting and critiquing but also subjected to imperial designs and hegemony, black historians better understood cultural affinities beyond the nation state or nationalism.[4] “Neither political nor economic structures of domination are still simply co-extensive with national borders,” Gilroy argued, a point that proved true in the age of colonies and empires, and feels equally accurate today. Due to their marginality within these structures, Kelley noted, black historians employed transnational frames well before the field adopted the same methodology in the 1990s.

In addition to political ideas, within the Black Atlantic, new musical forms emerged and circulated both as a means of identity and culture but also as a form of communication. “Music, the grudging gift that supposedly compensated slaves,” noted Gilroy “has been refined and developed so that it provides an enhanced mode of communication beyond the petty power of words—spoken or written.”[5] Not only did hip hop emerge from “routed and re-rooted Caribbean culture” it travelled along the same “transnational structures of circulation and intercultural exchanged established long ago.”[6]

Connections between rap and the Black Atlantic filtered into more popular works. Jeff Chang’s history of hip hop, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, begins in Jamaica, travels to the North Bronx and Long Island, and then across the continent to Southern California. The minds of black folk carried cultural and political revolution through hip hop; this uniquely American form of music later gained popularity with suburban whites as the genre exploded and redefined American culture forever. Take language for example. When on an early 2000s broadcast of Meet the Press, the late Tim Russert asked some senator in Nebraska if he felt “dissed” by the president’s comment; clearly more than a few things had changed.

![[Haitian Revolution], "Revenge taken by the Black Army for the cruelties practised ... by the French", 1805, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress](https://earlyamericanists.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/haitian-revolution_revenge-taken-by-the-black-army-for-the-cruelties-practised-by-the-french.jpg?w=304&h=393)

[Haitian Revolution], “Revenge taken by the Black Army for the cruelties practised … by the French”, 1805, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Gilroy further acknowledged the Black Atlantic’s transnational highways along with the ways in which its cultural progeny, namely hip hop and rap, boomeranged back. The African American identity shaped in equal parts by diverse voices like Public Enemy, N.W.A. and ACTQ unsurprisingly found popularity in “black Britain,” a success built on the same routes of exchange established by the Black Atlantic.[7] In America, rap operated, as Chuck D famously noted, as “Black CNN”; now it arguably speaks for an increasingly broader swath of the electorate making its message that much more complex but also more pervasive. You hear it in flows and beats of revolution through iPhone ear buds made in China on albums like We Got It From Here in the voices of its descendants: Phife Dawg, Q-Tip, and Jarobi.

Today hip hop could be described as the most pervasive transnational musical form, yet its purveyors in the U.S. and throughout the West remain largely outside the majority, excluded from political and economic power. It gives voice to a decided underclass, even if unevenly, thereby continuing a long tradition. The Black Atlantic produced musical forms that expressed the “protracted battle between masters, mistresses, and slaves,” writes Gilroy.[8] These earlier incarnations too communicated ideas, often revolutionary ones conveying the “unspeakable” but not inexpressible terrors of slavery. On its new album, ATCQ also gives voice to similar terrors—cop shootings, societal fragmentation, damaging conspiracy theories, political marginalization in the face of authoritarianism and more. In the end, the Black Atlantic has performed revolutionary work reconfiguring our conceptions of the West, culture, and the nation state. It continues to do so.

_________________

[1] Dick Hebdige’s, Subculture: The Meaning of Style might be as if not more significant and also addresses the Black Atlantic in it own way through Hebdige’s discussion of reggae, the origins of British skinheads, and the nation’s Jamaican population.

[2] Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, (1995), 15.

[3] Mimura, Glen, Ghostlife of Third Cinema: Asian American Film and Video (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 11-12.

[4] Robin Kelley, “But a Local Phase of a World Problem: Black History’s Global Vision, 1883-1950,” Journal of American History 86, no. 3 (1999): 1045-1077.

[5] Gilroy, The Black Atlantic, 76.

[6] Ibid., 33, 87.

[7] Ibid., 87.

[8] Ibid., 73-74.