Return guest poster Mairin Odle is an Assistant Professor of American Studies at the University of Alabama. She is currently writing a book, Skin Deep: Tattoos, Scalps, and the Contested Language of Bodies in Early America.

A few years ago, I was designing a new course, one that would fulfill a writing distribution requirement at my university. I knew I wanted to find ways to engage the class with the creative aspects of writing, not just the mechanics; I wanted to show my students how ideas develop, how revisions matter, and how classrooms could be collaborative spaces where we collectively care about our work rather than churn out assignments. So on the first day of class, I promised them (perhaps rashly) that I would write a final essay alongside them.

Deciding to write alongside my students and share my work with them came about, in part, as an effort to keep myself honest about writing during the semester, when the busyness of teaching made it all too easy to avoid. It also seemed like a way to test out ideas that weren’t directly related to my book project. The first class I incorporated this approach into was a course on representations of Native Americans in pop culture, meaning that TV, film, literature, advertising and more were all eligible topics for the students’ (and my) work. I chose a film (The Revenant) about which I had some things to say, and began drafting ideas in the early weeks of the course.

I encourage students to think of this course’s final project as a long-form magazine essay or commentary on a cultural artifact: they are expected to do research and to cite scholarly sources, but are also free to write their analysis in ways that sidestep the conventions of standard paper-writing. If, for example, they want to write a critique of Disney’s Pocahontas that interweaves a first-person account of their childhood memories of watching the film with their contemporary observations and scholarly analysis, they’re encouraged to do so. While some students are initially puzzled by the assignment’s departure in style from the formal papers they’re used to doing, many come to embrace it—and I find their writing more interesting to read when their own wry, or earnest, or enthusiastic voices come through. Much like Christopher Jones’s experiences with assigning “unessays,” I’ve found that providing students with some creative leeway can result in much stronger work.

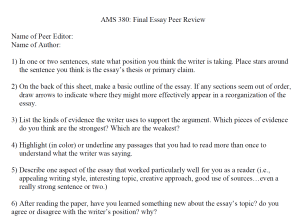

Major writing assignments in this course are scaffolded, meaning that students first submit a topic proposal, then complete a bibliography, partial drafts, a peer review, and ultimately a final draft. As I had promised the class at the beginning of the semester, I completed each major step just before they did. Since the assignment’s parameters and style were different from a standard research paper, this allowed me to demonstrate my expectations for the piece. I shared my topic proposal with the class as a sample before they wrote their own, and asked the entire class to workshop my draft the same week they did peer reviews for one another.

What I’ve found: students appreciate having an example. They want to know how to develop an idea, find research materials, or revise an argument when they find new evidence—all of these questions are easier to address when I have the example of my own project to refer to. It also helps me avoid the temptation of doing their work for them: instead of using one student’s project as a class example and describing their possible sources (and then receiving a bibliography from that student consisting of those books, and only those books, that I mentioned in class), we use mine and brainstorm keywords I might use in library searches.

Students also appreciate the commitment I make to them. It matters to them to see me dealing with writing challenges: they are relieved to learn that I too have a hard time coming up with an essay title, or that I occasionally (okay, frequently) leave comments to myself in early drafts like **NEEDS BETTER EXAMPLE**. Some friends and colleagues, when I’ve told them about having students read my work-in-progress, have suggested this must require deep reserves of bravery on my part. This has not been my experience: if anything, my students are generous to a fault. They are often anxious about offering even the smallest critiques of my work—a student once announced at the beginning of class that it “felt too weird”—but I find that to be another good reason for doing it.

To get them over that hurdle with the peer review, I invite the class to comment on what they thought the key idea or main point of my draft was, what they wanted to learn more about, what seemed like it didn’t fit with the rest of the piece. These questions usually prompt more conversation, and demonstrate to students that workshops or peer reviews are not about calling out someone for their shortcomings, but rather about helping them extend their analysis or reminding them of angles they might have overlooked. Realizing that they can provide substantive feedback without being an expert (and without being mean or harsh, as they often worry) gives them a model for how to review one another’s work.

The idea hasn’t always proceeded as smoothly as I envisioned when I first promised my students to write alongside them: sometimes with all my other teaching and research responsibilities, I’ve fallen behind schedule, causing me to pull together last-minute drafts. That’s been a good reminder about the similar circumstances that students might find themselves in. While I haven’t given up on the idea of due dates, I find myself thinking more carefully about when and what they are for when designing assignments.

Overall it’s been a valuable exercise, and one that I’ve implemented not just in that initial course but in other ways in my teaching. A senior taking an independent study with me last fall was writing an article-length paper, so I pledged to her that I’d revise one of my own article drafts for submission during the same semester, and that we’d discuss our revisions together. (My student ended up submitting her article to a journal at the end of the semester, while it took me another four months.) Even if I do it at a sometimes glacial pace, this process still gets me writing and drafting ideas during busy semesters. Ultimately, writing alongside my students makes my course a space of mutual accountability—and hopefully, showing my students that I take the writing project seriously enough to participate encourages them to do the same.

@MairinOdle

Super helpful. Makes me want to teach again.