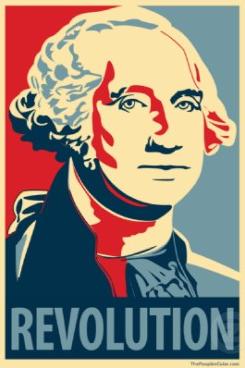

A relatively quiet week here; with the semester now underway everywhere, it’s probably not such a bad thing that we have fewer links to share. In any case, a little Revolution, an unidentified diary, and a forgotten war … on to the links!

A relatively quiet week here; with the semester now underway everywhere, it’s probably not such a bad thing that we have fewer links to share. In any case, a little Revolution, an unidentified diary, and a forgotten war … on to the links!

Tag Archives: Popular History

Sanitizing History

For the last few years, there has been a recurring news item in early January that sets my historical rage going. The repeated refusal of the Baseball Writers Association of America to elect Mark McGwire and others suspected of steroid use in the 1990s and early 2000s was bad enough. This year tipped me over the edge; the idea that neither Barry Bonds nor Roger Clemens deserve a place in the Hall of Fame is nothing short of preposterous. For better or worse, McGwire, Sosa, Clemens, and Bonds defined an era in which baseball regained its popularity after a self-destructive strike in 1994. For the hallowed halls of Cooperstown to pretend they never really existed is willfully sticking heads in the sand.

Of course, the sanitizing of history is not limited to the game of baseball. Every year, the NCAA comes down with ‘sanctions’ on college sports programs for a series of violations, whether academic, financial, or moral. Most typically, those programs are asked to ‘vacate’ their wins – doing nothing to actually award wins to the losers. And the sorry mess of the Lance Armstrong saga reflects a similar tale – those consulting the record books will simply be told that no-one won the Tour de France between 1999 and 2005, as if the race had never been run. At least the ‘vacation’ of title or a blank space in the annals encourages the casual observer to do some further reading on the circumstances. At root, though, it is a cop-out – if the record books don’t give us the nice morality tale that we’d like to see, we just press the delete button and hope that no-one comes to notice. Continue reading

Where Have You Gone, Gordon Wood?

Gordon S. Wood is perhaps the most prominent of the many Bernard Bailyn-trained historians to emerge from Harvard in the 1960s and 1970s, including Richard Bushman, Michael Kammen, Michael Zuckerman, Lois Carr, James Henretta, Pauline Maier, Mary Beth Norton, and many others. In the late 1960s, Wood’s dissertation-turned-first-book, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787, had arguably as large an impact on the field as his mentor’s Ideological Origins of the American Revolution did a few years before, both helping to usher in the heady days of the “republican synthesis.” This is all to say that Wood had earned himself a prominent spot in the field of early American history from pretty much the very start of his career. However, subsequent generations of early Americanists have grown increasingly hostile to not only Wood’s work but to the man himself. This leads to the question: Why is it acceptable (or even praiseworthy) behavior among early Americanists to treat one of the most important historians in the field in the last century disrespectfully? In this piece, I’d like to talk about Gordon Wood’s career trajectory, suggest that other historians’ reactions to him reflect not only Wood but on historians themselves, and ask whether that might give us even a fleeting insight into generational differences between early Americanists. Continue reading

is perhaps the most prominent of the many Bernard Bailyn-trained historians to emerge from Harvard in the 1960s and 1970s, including Richard Bushman, Michael Kammen, Michael Zuckerman, Lois Carr, James Henretta, Pauline Maier, Mary Beth Norton, and many others. In the late 1960s, Wood’s dissertation-turned-first-book, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787, had arguably as large an impact on the field as his mentor’s Ideological Origins of the American Revolution did a few years before, both helping to usher in the heady days of the “republican synthesis.” This is all to say that Wood had earned himself a prominent spot in the field of early American history from pretty much the very start of his career. However, subsequent generations of early Americanists have grown increasingly hostile to not only Wood’s work but to the man himself. This leads to the question: Why is it acceptable (or even praiseworthy) behavior among early Americanists to treat one of the most important historians in the field in the last century disrespectfully? In this piece, I’d like to talk about Gordon Wood’s career trajectory, suggest that other historians’ reactions to him reflect not only Wood but on historians themselves, and ask whether that might give us even a fleeting insight into generational differences between early Americanists. Continue reading

The Week in Early American History

Happy New Year! We took last week off while so many of us were in New Orleans for AHA, so the set of links covers just a bit more than the past seven days. From here on we should be back to our regular schedule every Sunday morning.

Happy New Year! We took last week off while so many of us were in New Orleans for AHA, so the set of links covers just a bit more than the past seven days. From here on we should be back to our regular schedule every Sunday morning.

The Founders, the Tea Party, and the Historical Wing of the “Conservative Entertainment Complex”

Following the recent election, much has been made of the alternative reality created by the “conservative entertainment complex.” However, conservative media has not only created its own contemporary reality; it has also created its own historical reality, through what one might call the historical wing of the conservative entertainment complex.

In recent years, men like David Barton, Bill O’Reilly, and Glenn Beck, among numerous others, have written a number of books on eighteenth-century figures and events. But though they claim to be getting their principles directly from “the founders,” what they are really doing is giving their principles to the founders and the eighteenth century, more generally. This revisionism, promoted by conservative think tanks, was lapped up by hardcore conservatives and perhaps no group of people has been a more receptive audience than those who identify themselves as supporters of the Tea Party. Continue reading