We talk a lot about accessibility in historical writing. Many of us worry whether the academic historical profession has much to say to a broad popular audience. It’s a pretty old form of anxiety. But what do the general public in the United States really want from their history books?

We talk a lot about accessibility in historical writing. Many of us worry whether the academic historical profession has much to say to a broad popular audience. It’s a pretty old form of anxiety. But what do the general public in the United States really want from their history books?

A few days ago, I decided to try an experiment. I collected all the one-star customer reviews at Amazon.com for the last twenty years of Pulitzer Prize winners in history. (No award was given in 1994, so I included books from 1995 to 2014.) I wanted to see whether I could identify common complaints. Obviously, this wouldn’t be a very scientific experiment, but at least it would be reasonably systematic—slightly better, perhaps, than relying on anecdotes from acquaintances.

As I expected, some of the reviews were amusing. There was, for example, a review that complained about the lack of “pictures or graphs” in the audio CD version of a book. Another reviewer observed that the author “lives in Mass., which probably pins him as an unrepentant Federalist or a modern day fascist.” (Who hasn’t entertained that thought at some point?) Another admitted that the book was “an enlightening one”—but “one sentence, [on] p. 375, makes you wonder.” My favorite was the review observing that Daniel Howe’s What Hath God Wrought has “a low amount of information per page.”

Actually, my favorite is a tie. I’m also very fond of this one: “Only the Bush administration could produce such a pack of lies. The Salk vaccine ‘safe?'”

Of course, Eric Foner’s Abraham Lincoln book drew out one very angry neo-Confederate, upset (among other things) that “no true southerner sits on the Pulitzer Selection Board” and “Joseph Pulitzer was a thief, liar, and an untrustworthy Union mercenary paid to kill Southern women and children.”

I collected all of these one-star reviews—115 in all—and started trying to categorize their specific complaints.

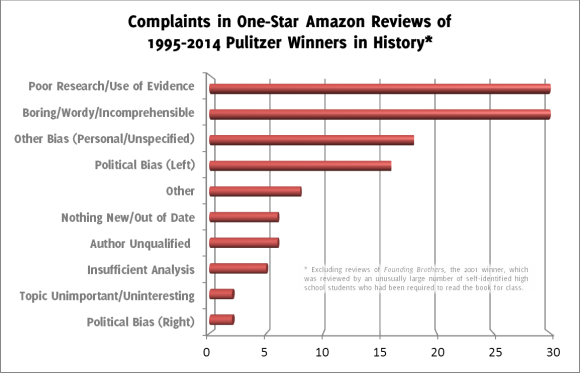

First, I decided to exclude the reviews of the 2001 winner, Joseph J. Ellis’s Founding Brothers. This was a hard call, but that book was an outlier in important respects.* That left me with 80 single-star reviews to consider. I drew up a list of possible categories and tallied up the number of reviews falling into each category. (I decided a review could make multiple complaints, but none of them could make more than three. In the end, few reviews fell into more than two categories anyway.)

Unsurprisingly, I found that 30 reviews complained about boredom, dryness, wordiness, or incomprehensibility—what we tend to call a lack of “accessibility.” Nearly all the Pulitzer winners, whether they were published by universities or by trade presses, prompted these complaints.

Unsurprisingly, I found that 30 reviews complained about boredom, dryness, wordiness, or incomprehensibility—what we tend to call a lack of “accessibility.” Nearly all the Pulitzer winners, whether they were published by universities or by trade presses, prompted these complaints.

Also unsurprising were the many complaints about liberal or left-wing bias. I counted 16 complaints about left political bias, 2 complaints about right political bias, and 18 complaints about bias that could not be placed in either category. (These typically implied the author showed some sort of personal hostility toward her subjects.) Among reviews with an identifiable partisan inclination, complaints about left-wing bias clearly dominated.

All of that was predictable. As I started tabulating complaints, however, I was struck by other things. Most importantly, the one-star reviewers surprised me with how substantive their complaints were. In a handful of cases, they provided detailed lists of alleged inaccuracies. In many more cases, they at least attempted to show that their ratings were responses to scholarly shortcomings. Out of 80 reviews, 30 complained about poor use of evidence or unsubstantiated claims on the part of the author; 6 complained that the book provided nothing new in the way of information or interpretation; and 5 complained that the author did not analyze the topic in enough depth. (Very few of the reviewers involved seemed to be professional academics, though at least one was.)

In other words, I counted roughly the same number of complaints about scholarly quality (41) as about bias (36)—though of course these complaints often appeared in the same review.

Crucially, however, complaints about scholarship often seemed to be motivated by underlying complaints about political bias. The Hemingses of Monticello, the 2009 winner by Annette Gordon-Reed, provided several good examples of this confluence. One typical reviewer called the book’s Pulitzer “a sad testimonial to our culture of political correctness, and a terrible indictment of our left-leaning academic institutions that celebrate such shoddy research and opinion-laden work.” Another managed to combine complaints about evidence, wordiness, and bias in a single demeaning image: “Her manuscript ought to have been passed through the sieve of serious historical scholarship instead of being plumped up with the Hamburger Helper of her agenda.”

A review of another book presented this in equally stark terms: “About halfway through the book I began to wonder if this was a history book or a political statement.”

Such reviews raise the question whether it’s possible for scholarly historians to address other barriers to wider public appreciation apart from the political discomfort their work can cause. When a reviewer implies that “an objective examination” is incompatible with “being a liberal,” or another reviewer contrasts being “objective” and having a coherent narrative with an author’s supposedly “constant put down of everything American,” we have reason to think that the problem of accessibility might be part of a deeper problem of public taste. The Hemingses of Monticello is a large book about an elusive subject, but part of the reason some readers find it wordy or unconvincing is that they resist fully entering the world it creates—a world that is a very uncomfortable place for them to imagine.

On the other hand, it is also true that the most consistent complaint from these scathing reviews was that the books were dry or impenetrable. This complaint appeared in reviews of almost every book, often apart from any discernible complaint about bias. The most plausible view of the evidence at hand is that accessibility is a real problem for historical scholars.

With that in mind, I think it’s important to observe that five books—Alan Taylor’s William Cooper’s Town, Edward Larson’s Summer for the Gods, Steven Hahn’s A Nation Under Our Feet, David Hackett Fischer’s Washington’s Crossing, and Gene Roberts’s and Hank Klibanoff’s The Race Beat—had no single-star Amazon reviews at all.

I will leave it for the reader to decide whether that is because these five books are so accessible, so unthreatening, or so unread.

____________________

* The 35 single-star reviews (out of nearly 600) for Founding Brothers would have skewed the results. No other book in the list came close to that number of reviews. More importantly, a very high number of the negative Founding Brothers reviews came from self-identified high school students reading the book on assignment. That was rarely true for reviews of the other books, and I decided that accessibility to high school students is a different thing from accessibility to adults. (Had I included these Founding Brothers reviews, I would have counted far more complaints about dryness, wordiness, and boredom.)

Fascinating exercise, especially in light of THE ECONOMIST’s ill-fated review of Ed Baptist’s book. Did you tabulate which of the Pulitzer-prize winners had the most reviews (excepting Ellis) and which had the most five-star reviews? That information would also provide clues about what the mythical “general audience” finds accessible–or perhaps just affirming of their pre-conceived biases.

Thank you, Rosemarie. I didn’t collect the totals for all reviews at the time, but I can provide them now, along with the total number of one-star reviews for each book:

No Ordinary Time by Doris Kearns Goodwin: 6 one-star reviews / 576 reviews in all

William Cooper’s Town by Alan Taylor: 0 / 16

Original Meanings by Jack Rakove: 2 / 36

Summer for the Gods by Edward Larson: 0 / 85

Gotham by Edwin Burrows and Mike Wallace: 2 / 87

Freedom from Fear by David Kennedy: 1 / 151

The Metaphysical Club by Louis Menand: 4 / 108

An Army at Dawn by Rick Atkinson: 11 / 748

A Nation Under Our Feet by Steven Hahn: 0 / 7

Washington’s Crossing by David Hackett Fischer: 0 / 230

Polio: An American Story by David Oshinsky: 2 / 96

The Race Beat by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff: 0 / 22

What Hath God Wrought by David Walker Howe: 4 / 143

The Hemingses of Monticello by Annette Gordon-Reed: 27 / 167

Lords of Finance by Liaquat Ahamed 3 / 231

The Fiery Trial by Eric Foner: 1 / 77

Malcolm X by Manning Marable: 15 / 168

Embers of War by Fredrik Longevall: 1 / 160

The Internal Enemy by Alan Taylor 1 / 33 [this may have been a mistake; the comments are positive]

Interestingly, that is a total of 80 1 star out of 3141 total reviews. In other words, 1 star reviews make up only 2.55% of the total. Equally interesting is that 5 of the books have no 1 star reviews: that’s fully 25% of the sample.

It seems that a good fraction of the 1 star reviews come those who are engaged with the book, even if negatively. This could account for the detailed comments which you reported. Could it be that the 35 1 star reviews for “Founding Brothers” are more typical of unengaged readers?

This may be the best Junto post ever!

Agreed. Doesn’t get more original than this. Bravo!

Great post. It is interesting to think that maybe these books became pulitzer prize winners because they DO have an agenda. Maybe what makes them disliked by the 1-stars is also why they are so loved by the 5-stars. My parents (non academics) cannot say enough good things about The Hemingses of Monticello. Despite having read it myself, my parents insist on telling me all the wonderful things about that book. And they never got round to reading William Cooper’s Town (my favorite).

Great stuff, JW. I think the fact that Pulitzer Prize awards often fit within a cultural “moment,” it would make sense to get some negative reviews from people who have cultural angst.

Great post! I think this illustrates a broader point about the long term value of these kinds of crowdsourced book reviews for understanding reader response in the future. Folks interested in that, might enjoy this bit I wrote about the potential long term value of goodreads reviews. http://www.trevorowens.org/2011/01/reading-goodreads-a-note-to-historians-of-the-future/

Reblogged this on DailyHistory.org and commented:

Jonathan Wilson at The Junto has sifted through all of the one star reviews of Pulitzer Prize winners in history to see if he could identify a common complaint. I have to admit that I enjoy reading one star reviews. A well written scathing review can be a lot of fun. Of course, a large subset of one star reviews of good books are written by crazy people which are often hilarious. Check out Wilson’s conclusions in this enjoyable and enlightening post.

I was a History major in college, but by no means consider myself an expert. Out of all the books my professor assigned, the two by David Hackett Fischer (Paul Revere’s Ride, and Washington’s Crossing) stood out to me the most. He was able to combine a gripping narrative with historical fact, in a way that I never viewed those books as assignments but truly enjoyable reads. I loved a lot of the books I was assigned, but those two were different.

Reblogged this on Gunlord500 and commented:

Not gonna lie, a lot of those 1 star ones made me lol. Amazon.com reviews may not be as bad as Youtube comments, but they have their moments.

Jonathan wrote: “We have reason to think that the problem of accessibility might be part of a deeper problem of public taste.”

I have long argued this was the case and Jonathan’s excellent piece only further confirms the notion for me. When readers allege “bias” or “lack of objectivity,” they are often doing so because the book does not conform to their preconceived notions or opinions. That reaction–also seen in studies showing that people generally consume news and media that conform with their opinions–is common. However, there is a deeper underlying problem with those kinds of statements and reviews. It’s not that they perceive disagreement as lack of objectivity, but that they perceive “objectivity” in historical writing to be a tangible, achievable goal. This is also reflected in the standard charge made against “revisionist historians.” When I introduce the concept of historiography to my students (early on in every course), I tell them, “ALL history is revisionist history.” And for many, historiography is not a concept that is immediately intuitive, though it doesn’t take long for them to understand it and incorporate it into their historical thinking. Unfortunately, college students (especially where I teach at the moment) are not representative of the general population in this respect.

Is that a problem of pre-higher education? Is it a problem within our culture more generally? Is it possible to address the problem on a large scale? Yes, yes, and I hope so, otherwise conversations about the problem and (even worse) initiatives to address it are all in vain. This is just one of a number of deep flaws in the role (or non-role) of historical thinking in contemporary American culture and one of the reasons why I continue to believe wholeheartedly that we academic historians are fooling ourselves when we say, “If only we learned to write better, more ‘general readers’ would buy and read our books.”

Agreed. And to your point regarding flaws in historical thinking within American culture I may add that popular docu-dramas on television networks (specifically the History Channel with “America the Story of Us,” “The Men Who Built America,” and among others) might possibly exacerbate those flaws in historical thinking by reinforcing preconceived beliefs of American history from what is perceived as an authoritative or objective source. This is mere speculation, but I can see how programs such as these might have that influence on the general population whose historical knowledge may be limited.

Negative reviews often are more substantive than positive reviews. A potential purchaser/reader who can disregard the perspective of the commentator and look strictly at the content of what they say should be able to determine whether or not they want to spend the time on the read. Often I have purchased books based on the content of negative reviews. Likewise, I have not purchased books based on the content of positive crowdsourced reviews. Whether someone else puts 5 shiny stars or just one beside their comment is of little difference to me.

Ideally, I want people to enjoy what they read and to connect with it on some level. If someone wants to explore law through Friedman’s bone-dry “A History of American Law” or a John Grisham novel, then why not do just that.

Oh, jesus, I sincerely hope those books without single star reviews aren’t being neglected but are beloved; Taylor and Hahn are magnificent, although I have doubts anyone actually wades through Fischer…

Very interesting discussion, but another thing to keep in mind is the selection effect of winning a significant prize. Amanda Sharkey at UoC recently published a study showing that reader reviews *decline* following the awarding of a major prize (she studied fiction, but mechanisms are similar). The study is summarized here (http://phys.org/news/2014-02-negatively-award.html), or available in full from _Administrative Science Quarterly_. The mechanism she proposes is very much in evidence in this discussion: Books that win awards attract broader readership by virtue of winning the award, and some (many) of these *new* readers don’t like the work. Certainly the bored high-school students would fall into this category. They likely would not have been assigned _Founding Brothers_ if it hadn’t won the Pulitzer.

David

I am a serial reader and made a lot of money in high school by summarizing & reviewing books for other students from the approved reading list and could produce at least 5 summaries & reviews for each book.

I think a lot of the one star reviews are awarded because the person was forced to do it by a subject requirement..

“one star because it kept me away from the TV / computer game high school booze up or dance”

Okkie

I review the history books I’ve read and put the reviews on Amazon. I find it very interesting how my reviews that get negative remarks or dislikes from others are almost always Civil War books. The Lost Cause crowd has a lot of trolls that like to go through the reviews and mark them for dislike without having actually read the book. It shows a real issue with the Amazon review process.

I reviewed Rakove’s Original Meanings and gave it a good review. Someone disliked the review and you can pretty well bet that was due to a political bias. That is happening quite often as well for books that touch upon things like the Constitution. However, the Lost Cause crowd definitely outnumbers the other group, but based upon comments left behind I think they’re often the same type of individuals.

I have found it increasingly difficult to take Amazon.com reviews seriously. Lately I’ve got negative reviews for my books attacking them for long, intricate, and prolix sentences. This is not true — my editor is a determined sentence-chopper, and so am I. But the reviewers insist on claiming to find my prose problematic. I’ve also got attacks based on politics, attacks based on charges of “political correctness,” and attacks based on claims of poor research — mixed with attacks based on excessive documentation (?!). Thus, studying Amazon.com reviews, however amusing the results may be, strikes me as not very useful, to be kind.

Margins of Error

How many reviewers were educated, well-read, patient readers who were capable by training and temperament to absorb heavy text and by contrast how many were simply bored mainstream readers looking to be entertained?

How many reviewers understood that history is an interpretation of events filtered through the sieve of human opinion and not an unequivocal GoPro movie immortalized on computer chip?

How many reviewers were pissed off by an ongoing political election and were laboring under a thick layer of bipartisan ire while they weighed these books for political bias?

How many reviewers were actually young students forced to purchase and read said volumes who were then striking back against their professors using an anonymous electronic club?

How many reviewers read these books with an attitude of learning and expansion rather than one of ethnocentric gratification and ego stroking, particularly of the religious and political kind?

How many of the reviewers were who they actually claimed to be–not a writing competitor, uninvolved family member, or Amazon troll (it’s a thing) looking to fill a few minutes while their Netflix selections download?

How many of the reviewers were mentally competent, calm, focused, and alert when they placed their reviews?

The customer ratings can’t tell us. So, take online reviews of this ilk with a giant bucket of salt and don’t worry too much about how the stars stack up. Because humans.

Reblogged this on owen9009.

The real problem is that you’re using Amazon. Anyone with any sense at all can see that Amazon only survives by catering to the lowest rung of the intelligent. Nobody who cares about intelligent writing cares what the reviews on Amazon say. The proof is THAT Amazon is the largest online sales portal in the world; it could only get that way by being useful and appealing to the lowest common denominator, just like any politician.

I’m not sure it is true that Amazon appeals to the lowest common denominator. You could say the same about any bookshop. We all have different tastes. I enjoy reading books that seem dry as dust to others and am never put off by those kind of reviews. There is an art to reading reviews, just as there is an art to any good conversation where you listen as well as speak.

Reblogged this on anilkumarchehrabhai.

This is such an important study on accessibility, writing, and research. Thank you for compiling this data. Even though it is not “very scientific,” as you say, it is worth trying to understand.

Reblogged this on Illumination.

Reblogged this on pigeon weather productions.

Well done. Great idea and interesting results 🙂

HMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM, makes one wonder who really writes Amazon material…………all very questionable.

It’s a sad world.

Reblogged this on ramesh5.

I love stuff like this! I feel like I missed my calling in some sort of meta-analysis.

Reblogged this on herstorian329 and commented:

Great info for aspiring historians.

Reblogged this on herstorian329 and commented:

Great info for aspiring historians.

I disagree that this is unscientific. A qualitative approach in social sciences would do pretty much what you just did. They might have a few people developing the categories and develop a process for resolving disagreements among raters. But, it sounds like the decisions you made are unlikely to be met with serious critique. Honestly, that looked like science to me. Fascinating approach.

Reblogged this on Slightly Left of Centre.

Reblogged this on darrelltomlin66.

Reblogged this on kabuya25's Blog.

Reblogged this on rhinoassam.

Great post, thanks for doing the work!

It certainly makes sense for you to have excluded the data from Founding Brothers, but it sounds like some high school teachers could benefit from the information anyway!

Reblogged this on carmeng8 and commented:

So Amazon book reviews are not the most reliable…surprise surprise

Reblogged this on A Vase of Wildflowers.

I’ve come a few bad reviews of myself on Amazon but this makes me feel a bit better….a lot better…superior. I’m so glad I came across this.

Pingback: One-Star Amazon Reviews of Pulitzer Winners | Suril Pathak

Interesting stuff!!!

This is interesting and probably not surprising given that bad writing is the most likely bane of the academic writer. Gotta believe the “What Hath God Wrought” comment was meant to be sarcasm.

Pingback: One-Star Amazon Reviews of Pulitzer Winners | J.A. Stinger

Understandable….Pulitzer isn’t what it used to be….it seems to be more involved with play “trendy” catchword bingos, than with any level of journalistic or narrative integrity! So why not show a diversity of responses…? yes.

i never read Amazon reviews as i rarely purchase books from Amazon.

you might use LibraryThing as well. its a little more out of the way so you might get smarter peope there. amazon doesnt really cater to academics now does it