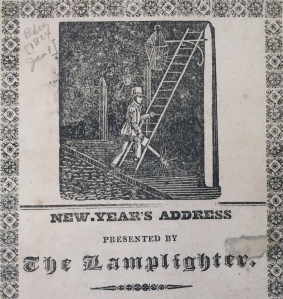

Every day they took apart the city, and put it back together again. New Year’s Day was no different. They worked while dawn, then dusk, threaded the sky, to patch up narrow streets. Lamplighters, an urban mainstay heroicized by Maria Susanna Cummins’ fictional “Trueman Flint,” heaved up their wooden ladders to trim wicks and refill oil pans. Along with the dry-dirtman, city scavengers spread out to collect loose trash. The scene might have been Boston, Philadelphia, Charleston, New York, Baltimore, Cleveland, St. Louis—and set anytime from the Revolution to the Civil War. Newspaper carriers, mostly young boys, filtered along the avenues. Tucked in sheets of newsprint, the city’s youngest workers also carried on a curious tradition: the New Year’s address. A rhyming blend of local-color writing and cultural commentary, the New Year’s address recapped the past and looked ahead. Laden with ornamental tombstone borders and often draped over double columns, each address ended with a plea for an annual gratuity.

Every day they took apart the city, and put it back together again. New Year’s Day was no different. They worked while dawn, then dusk, threaded the sky, to patch up narrow streets. Lamplighters, an urban mainstay heroicized by Maria Susanna Cummins’ fictional “Trueman Flint,” heaved up their wooden ladders to trim wicks and refill oil pans. Along with the dry-dirtman, city scavengers spread out to collect loose trash. The scene might have been Boston, Philadelphia, Charleston, New York, Baltimore, Cleveland, St. Louis—and set anytime from the Revolution to the Civil War. Newspaper carriers, mostly young boys, filtered along the avenues. Tucked in sheets of newsprint, the city’s youngest workers also carried on a curious tradition: the New Year’s address. A rhyming blend of local-color writing and cultural commentary, the New Year’s address recapped the past and looked ahead. Laden with ornamental tombstone borders and often draped over double columns, each address ended with a plea for an annual gratuity.

Many addresses, like the one issued by African-American street sweeper Charles Hardy, chose to underline their jobs’ rigor. “Yes, I’m alive, in spite of fate / Tho’ hard has been my lot of late; / Yet cold as is my winter bed, / ’Tis warmer than where sleep the dead.” So ran Hardy’s address to Bostonians for 1825, which wrapped up with a request to “give then the poor old man a mite.” Elsewhere, when the watchman addressed his “protected friends,” the message was simple: Reward local workers. As one dry-dirtman told housekeepers in 1834: “True, dirty are the pains we take, / There’s nothing in them funny; / And therefore, patrons let them make / This once, at least, CLEAN MONEY.”

Drafted by newspaper editors, city librarians, and eminent writers, the addresses speak volumes about how Americans interpreted the experience of hard labor in the industrial city. At some point, notable authors like Benjamin Franklin, Daniel Webster, the “Connecticut Wits” poets, and Alice Williams Brotherton, all took turns at the pen. Largely a cultural carryover from early modern England, the practice of tipping tradesmen on New Year’s Day spread throughout the colonies and lasted well into the twentieth century.

Drafted by newspaper editors, city librarians, and eminent writers, the addresses speak volumes about how Americans interpreted the experience of hard labor in the industrial city. At some point, notable authors like Benjamin Franklin, Daniel Webster, the “Connecticut Wits” poets, and Alice Williams Brotherton, all took turns at the pen. Largely a cultural carryover from early modern England, the practice of tipping tradesmen on New Year’s Day spread throughout the colonies and lasted well into the twentieth century.

In his excellent overview of carriers’ addresses in the January 2008 issue of Common-place, scholar Leon Jackson observed that publication of such literature began in America in the 1720s, cresting between the 1760s and the early 1900s. “The addresses are, in fact, perhaps the most extensive literary genre of the colonial and early national period about which practically nothing has been written,” Jackson wrote. “This is a shame because they are fascinating documents from which we can learn a great deal about artisanal culture, the commercialization of Christmas, changes within the newspaper trade, the development of the middle class, and changing perceptions of youth, labor, and leisure.” Bridging patriotism and satire, wit and criticism, New Year’s addresses gave the “common man” (or woman) a voice—even if it called for some cultural ventriloquism—for over two centuries.

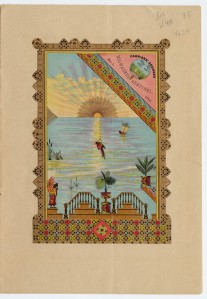

As the nation grew up, New Year’s addresses grew heavily stylized in word and image. Set in white paper or colored silk, they mirrored a nation imprinted by war and industrial change. On the page, the workers’ “look” and tone gradually shifted in key. The colonial dry dirt-man, once a popular broadside profile, was overwritten by the “fact-grinders” of 1851. Antebellum jabs at politicians and slavery were muted by the Civil War, replaced mainly by Victorians’ gauzy sentimentalism. In the 1870s and 1880s, early American traditions still cast a long shadow, and the New Year’s addresses persisted. But Western sunsets “à la Japonaise,” and bright-eyed newsboys inspired by Horatio Alger’s rags-to-riches tales, dominated the pages. Likely spurred by the Centennial International Exposition of 1876, some Victorian addresses even attempted to summarize all of American history in a few punchy stanzas. In 1847, the New York Sun’s big picture of the past overflowed with pageantry and pride for the “Pilgrim band” that shaped it: “These towns increase, and Cities soon become.— / The hall of legislature rears its dome. / Where did the wild beast in his hunger rave / Exists a nation generous and brave.”

As the nation grew up, New Year’s addresses grew heavily stylized in word and image. Set in white paper or colored silk, they mirrored a nation imprinted by war and industrial change. On the page, the workers’ “look” and tone gradually shifted in key. The colonial dry dirt-man, once a popular broadside profile, was overwritten by the “fact-grinders” of 1851. Antebellum jabs at politicians and slavery were muted by the Civil War, replaced mainly by Victorians’ gauzy sentimentalism. In the 1870s and 1880s, early American traditions still cast a long shadow, and the New Year’s addresses persisted. But Western sunsets “à la Japonaise,” and bright-eyed newsboys inspired by Horatio Alger’s rags-to-riches tales, dominated the pages. Likely spurred by the Centennial International Exposition of 1876, some Victorian addresses even attempted to summarize all of American history in a few punchy stanzas. In 1847, the New York Sun’s big picture of the past overflowed with pageantry and pride for the “Pilgrim band” that shaped it: “These towns increase, and Cities soon become.— / The hall of legislature rears its dome. / Where did the wild beast in his hunger rave / Exists a nation generous and brave.”

Within a few decades, the history culture of New Year’s addresses morphed into a more forward-thinking canon. As the Saratoga Sun told readers in 1873: “The world is not so wondrous as yore, / Nor yet so great a mystery. Through open door / Of Science, Lightning, Steam, and high emprise, We see the progress and the fall and rise / Of farthest nations, and we hear the din / Of daily commerce, as we gaze within…” Other late nineteenth-century addresses dove into the dilemmas of the moment, like farmers vs. railroads, or explored how new technology like the transatlantic telegraph cable “marks the march of science, too.” As general strikes erupted and unions grew, the New Year’s address took on a sterner tone of social reform. Carrier John F. Maguire, addressing patrons in The Iron Era of 1890, subdivided his appeal’s opening into “Apologetically”; “The Weather”; “Politics—Variegated.” He made an urgent call for greater social philanthropy and spoke of “Some Needs” to improve area schools. Just like his colonial forebears, Maguire topped off his New Year’s address with a ritual plea: “While for your good I gladly sing, / And to your door this tribute bring, / I trust that some responsive ring / Of change my call will greet.”

Within a few decades, the history culture of New Year’s addresses morphed into a more forward-thinking canon. As the Saratoga Sun told readers in 1873: “The world is not so wondrous as yore, / Nor yet so great a mystery. Through open door / Of Science, Lightning, Steam, and high emprise, We see the progress and the fall and rise / Of farthest nations, and we hear the din / Of daily commerce, as we gaze within…” Other late nineteenth-century addresses dove into the dilemmas of the moment, like farmers vs. railroads, or explored how new technology like the transatlantic telegraph cable “marks the march of science, too.” As general strikes erupted and unions grew, the New Year’s address took on a sterner tone of social reform. Carrier John F. Maguire, addressing patrons in The Iron Era of 1890, subdivided his appeal’s opening into “Apologetically”; “The Weather”; “Politics—Variegated.” He made an urgent call for greater social philanthropy and spoke of “Some Needs” to improve area schools. Just like his colonial forebears, Maguire topped off his New Year’s address with a ritual plea: “While for your good I gladly sing, / And to your door this tribute bring, / I trust that some responsive ring / Of change my call will greet.”

New Year’s addresses make for a fascinating flipbook of early American workers’ lives. For scholars weighing print culture’s impact, or studying the question of social class in American history, New Year’s addresses offer fruitful roads for further research. Brown University Library has helpfully digitized more than 900 newspaper carriers’ addresses. The Boston Athenaeum features several as online broadsides, and check out the many listings held at the American Antiquarian Society, especially the printer’s devil addresses. Via subscription access, you can explore Readex’s related riches, too.

New Year’s addresses make for a fascinating flipbook of early American workers’ lives. For scholars weighing print culture’s impact, or studying the question of social class in American history, New Year’s addresses offer fruitful roads for further research. Brown University Library has helpfully digitized more than 900 newspaper carriers’ addresses. The Boston Athenaeum features several as online broadsides, and check out the many listings held at the American Antiquarian Society, especially the printer’s devil addresses. Via subscription access, you can explore Readex’s related riches, too.

To all of our readers, we wish you a Happy New Year of writing and research!

Sara,

It is wonderful see the renewed interest in New Year’s addresses here and on Boston 1775 this year. A lovely new year’s present to all readers.

I’d also like to call readers’ attention to this checklist published by AAS and distributed by Oak Knoll. I was pleased to find an image of a carrier at a customer’s door that could be used for the book’s cover.

Caroline

A CHECKLIST OF AMERICAN NEWSPAPER CARRIERS’ ADDRESSES, 1720-1820. Gerald McDonald, Stuart C. Sherman and Mary F. Russo

Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 2000. 8vo. cloth, dust jacket. xvi, 170 pages. First edition. The newspaper carrier’s address, a printed holiday greeting, was a unique early American poetic form. Each New Year’s Day, newspaper carriers around America and Canada distributed printed verses to their customers in hope of a hefty tip. Often highly amusing and occasionally quite socially aware, these broadsides eulogized the dutiful carrier of the year gone by. For the first time, these… READ MORE

Price: $35.00 other currencies Order nr. 59170

– See more at: https://www.oakknoll.com/advSearchResults.php?dist_id=1#sthash.xuLulGMv.dpuf (and scroll down to this volume)

Thanks, Caroline, for sharing info here about the checklist. The more resources, the merrier!