In a series of classic science fiction stories, Isaac Asimov imagined a scientific discipline called “psychohistory”: a way to predict the future of an interstellar empire. Psychohistory could not foresee individual choices, but it could supposedly predict collective behavior over the course of millennia. At one point in the Foundation series, however, a charismatic figure named the Mule threatened to upend psychohistory’s predictions: he was a mutant, acting in ways the original model could not anticipate. In the universe Asimov imagined, the Mule alone seemed to possess true individual agency. Resisting a powerful model of human behavior, he offered instead a story about a person.

In a series of classic science fiction stories, Isaac Asimov imagined a scientific discipline called “psychohistory”: a way to predict the future of an interstellar empire. Psychohistory could not foresee individual choices, but it could supposedly predict collective behavior over the course of millennia. At one point in the Foundation series, however, a charismatic figure named the Mule threatened to upend psychohistory’s predictions: he was a mutant, acting in ways the original model could not anticipate. In the universe Asimov imagined, the Mule alone seemed to possess true individual agency. Resisting a powerful model of human behavior, he offered instead a story about a person.

I thought about the Foundation books when I read a recent essay by a French revolutionary historian. David A. Bell argues that the new American president’s unpredictable personal character “may force [future] social scientists and historians to look beyond their usual analytical tools.” In other words, scholars trained to seek impersonal “structural” causes of human behavior may not be fully equipped to explain the course of American politics after 2016. An old-fashioned “great man” or “heroic” model of historical behavior may prove useful.

I thought about the Foundation books when I read a recent essay by a French revolutionary historian. David A. Bell argues that the new American president’s unpredictable personal character “may force [future] social scientists and historians to look beyond their usual analytical tools.” In other words, scholars trained to seek impersonal “structural” causes of human behavior may not be fully equipped to explain the course of American politics after 2016. An old-fashioned “great man” or “heroic” model of historical behavior may prove useful.

I am not sure I agree with David Bell’s prediction. As far as historical theory goes, in fact, I can imagine historians reacting to the incoming administration in just the opposite way—by stressing the limits of individual power. However, I do think many historians will react to own their heightened sense of contingency by trying to shape events themselves—especially by producing accessible books, op-eds, and other pieces of public scholarship. If they do so, they will only intensify a shift that is already well underway in the historical profession.

Plenty of academically trained historians today want to tell stories non-academics will read. I say “tell stories” because fundamentally that is what historians do, even when it doesn’t look like it. (Even stories about big impersonal forces are still stories.) The problem—besides having so many other demands on our time—is that we are not always prepared to tell stories that make sense to non-initiates.

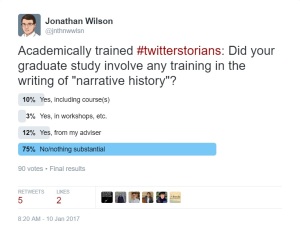

Ten days ago, I posted a Twitter poll asking historians whether they had received any training in how to write narrative history as part of their graduate studies. Ninety historians took the poll; 75 percent said they had not received any substantial training. Some clarified that this meant they had not been trained to write narrative at all, for any kind of audience.

Ten days ago, I posted a Twitter poll asking historians whether they had received any training in how to write narrative history as part of their graduate studies. Ninety historians took the poll; 75 percent said they had not received any substantial training. Some clarified that this meant they had not been trained to write narrative at all, for any kind of audience.

A few days later, I followed up by asking historians on Twitter what their own favorite guides for writing narrative were. Many people were ready with detailed responses, which apparently, in many cases, they had discovered on their own. Here are some of the most common or enthusiastic recommendations I received:

- Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life

- Verlyn Klinkenborg, Several Short Sentences About Writing

- Jack Hart, Storycraft: The Complete Guide to Writing Narrative Nonfiction

- Susan Rabiner and Alfred Fortunato, Thinking Like Your Editor: How to Write Great Serious Nonfiction—And Get It Published

- Mark Kramer and Wendy Call, eds., Telling True Stories: A Nonfiction Writers’ Guide from the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University

- James B. Stewart, Follow the Story: How to Write Successful Nonfiction

- John McPhee, “Structure: Beyond the Picnic-Table Crisis,” in The New Yorker

- Donna Seaman, interview with Erik Larson for Creative Nonfiction

- David Hackett Fischer, “The Braided Narrative: Substance and Form in Social History,” in Angus Fletcher, ed., The Literature of Fact

- Stephen Pyne, Voice and Vision: A Guide to Writing History and Other Serious Nonfiction

I am grateful to historians and editors including Amy Kohout, L. D. Burnett, Peter Ginna, Heather C. Richardson, Ronit Stahl, David Head, Charlie McCrary, and Justin Taylor for these and other suggestions. I can endorse several of those titles myself, particularly Storycraft and Telling True Stories.

It strikes me that most of these guides are written by journalists. Because of that, they offer invaluable advice for dealing with problems that historians routinely encounter without much training. By virtue of the same fact, however, academically trained historians probably have all sorts of specific practical questions these guides do not address. Some of those questions surely vary by subdiscipline.

As a new federal administration takes power in the United States, therefore, I am thinking about what else early American historians can do to help each other overcome our specific writing challenges. If there are often large gaps in our graduate training, as well as significant gaps in the advice offered by most narrative journalists, then how can we work together to fill these gaps?

Fascinating, but it explains a lot regarding the disconnect between academic historians and the general public.

This is a timely topic in that Doris Kearns Goodwin will be the featured speaker at an upcoming Boston University conference, “The Power of Narrative: Telling True Stories in Turbulent Times”. Sponsored by the College of Communication, the conference is largely pitched to mid-career journalists seeking to pursue or improve upon longer form narrative non-fiction, but the presence of Goodwin highlights the role of narrative in successful public history writing as well as the value journalism educators bring to promoting narrative across disciplines.

As a former journalist, I value what my own professional experiences have brought to my work as a fledgling historian, not only in terms of writing but also research. Journalists are generally not trained experts in any particular field that they may be writing about. Their expertise is in knowing how to become fluent enough in any field that they are able to accurately and effectively explain its issues to readers who are equally unfamiliar with the material.

That mission is at the heart of why journalists find value in narrative and why public historians focus on it as well. Stories can serve as effective models for grasping bigger trends. However, no individual story is capable of representing every possible outcome or aspect of a situation. Journalists will tell you the technical experts they consult frequently complain that even the most detailed resulting articles have failed to convey nuances that those in the field consider important.

When Jonathan writes that historians’ problem “is that we are not always prepared to tell stories that make sense to non-initiates”, I think he is tapping into an element of that same frustration. As historians, much of our work is about nuance and minutiae. We are constantly contributing nuggets to slowly and subtly reshape the pile of historiographical understanding. It can seem difficult to meaningfully convey the significance of those details to people unfamiliar with the bigger picture, but we are often loathe to abandon any detail as insignificant.

Scientists have the same problem, and are currently grappling with that issue with greater attention that they have in decades. The horrific decline of public faith in science has taught them they need to do a better job at “science communication” — a term intended to reflect the distinction between reporting research to colleagues and explaining its significance to the general public. One element of that communication is the role of narrative in making difficult concepts easier to understand through individual stories and examples.

Public history has long done just that, but few historians receive any training — much less at a graduate level — in those methods. If anything, many are taught to to become dismissive of public history altogether. Professional public history programs like that at my own school (University of Massachusetts Amherst) are changing that, but if more schools were to mandate that all graduate history students receive some exposure to the fundamentals of those methods, it would go far in improving historians’ ability to connect to the lay public.

I strongly believe that the methods of journalism and public history as well as the current efforts of the science community can help guide similar improvements in “history communication.” Their examples prove that we can learn to tell stories that matter.

Thank you for writing this important piece, Jonathan. Like many of the respondents to your twitter question, I did not receive any formal training in narrative history during graduate school, but narrative will be a key feature in my eventual book. The distrust of academic historians seems to be getting a lot of attention of late and while the disconnect between popular and academic history has many valid causes, a couple of points should be part of this discussion: authors, whenever possible, should avoid overly complex terms when simpler ones will do. Two, while it makes sense for stylistic purposes to vary one’s sentence structure, stacking one’s writing with overly long and complex sentences can be quite disorienting to the reader. I cannot tell you how many times I’ve opened up an academic history journal and after reading the opening paragraphs–paragraphs in my mind where an argument should start to become discernible–I think to myself…Huh? What in the world is this person trying to say? If I can’t understand your writing, then how limited is your audience? Since the 2008 recession, from which academic history has not recovered, I have seen article after article saying we need to make history “useful.” If the statistics on history undergraduate majors compiled by Robert Townsend and Allen Mikaelian are any indication, we are continually failing (admittedly many of the factors driving this troubling change are beyond individual historians’ ability to control). Perhaps a back-to-the-basics approach is needed…

John, thanks for your thoughtful post (and to Marla Miller for retweeting it). In addition to books about writing narrative nonfiction (I took a narrative nonfiction class at Boston U many years back with one of those authors, Mark Kramer, and it was great), I think we can learn a lot by READING masterful narrative nonfiction. I’m sure others have many to recommend, but I’d vote for Rebecca Skloot’s “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” Christopher McDougal’s “Born to Run” (it gets better every time I read it), David Grann’s “The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon,” Jon Krakauer’s books (“Into Thin Air,” “Into the Wild”), and Craig Child’s “Finders Keepers: A Tale of Archaeological Plunder and Obsession,” to name a few. And while we’re at figuring out how to interpret and retell history in a manner that might actually interest the general public, what can we learn from the huge popularity and attraction of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “Hamilton” on Broadway? Has history every been so hip or so hot? Let’s get HIM to keynote a conference on making history matter.

I had a professor who – in a capstone class – would in lecture encourage us to write interesting, “readable” history but then criticize the lack of academic verbiage in our papers.

Pingback: This Week in Online Intellectual History Reads–1.22.17 | s-usih.org

Pingback: Why History is More Than Just the "Facts" - Shot Glass of History