Guest poster Keisha N. Blain (@KeishaBlain) is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Iowa. She is a regular blogger for the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS). She is currently completing her first book entitled, Contesting the Global Color Line: Black Women, Nationalist Politics, and Internationalism. This post shares some additional insights into the racial violence Benjamin Park discussed following the Charleston shooting.

Members of the UNIA in Harlem, 1920s. Image: Black Business Network

Someone recently asked me why the black women activists I study were so determined to leave the United States. It was a question I had been asked many times before. As I often do, I explained the complex history of black emigration, highlighting how these women’s ideas were reflective of a long tradition of black nationalist and internationalist thought. I acknowledged the romantic utopian nature of these women’s ideas. However, I also addressed the socioeconomic challenges that many of these women endured and explained how the prospect of life in West Africa appeared to be far more appealing—especially during the tumultuous years of the Great Depression and World War II. I spoke about black women’s ties to Africa and the feelings of displacement many of them felt as they longed for a place to truly call home. It was the same feeling of displacement to which the poet Countee Cullen alluded when he asked a simple yet profound question: “What is Africa to me?”

In October of 1780, the governor of Quebec, Frederick Haldimand, warned against changing the laws and regulations of the British colony. It required “but Little Penetration,” he claimed, to reach the sobering conclusion that “had the System of Government Sollicited by the Old Subjects been adopted in Canada, this Colony would in 1775 have become one of the United States of America.” He continued, “Whoever Considers the Number of Old Subjects who in that Year corresponded with and Joined the Rebels, of those who abandoned the defense of Quebec… & of the many others who are now the avowed well wishers of the Revolted Colonies, must feel this Truth.”[1]

In October of 1780, the governor of Quebec, Frederick Haldimand, warned against changing the laws and regulations of the British colony. It required “but Little Penetration,” he claimed, to reach the sobering conclusion that “had the System of Government Sollicited by the Old Subjects been adopted in Canada, this Colony would in 1775 have become one of the United States of America.” He continued, “Whoever Considers the Number of Old Subjects who in that Year corresponded with and Joined the Rebels, of those who abandoned the defense of Quebec… & of the many others who are now the avowed well wishers of the Revolted Colonies, must feel this Truth.”[1]

I’m grateful to The Junto blog for inviting me to discuss how to publish a journal article. Although the views that follow are my own and the details of the process vary somewhat from journal to journal, I know from conversations with other editors that there is consensus on the essentials.

I’m grateful to The Junto blog for inviting me to discuss how to publish a journal article. Although the views that follow are my own and the details of the process vary somewhat from journal to journal, I know from conversations with other editors that there is consensus on the essentials. Historical knowledge plays an important role in the international business field. Ironically, as programs in the humanities are forced to justify their relevance to administrators, elected officials, and the general public, we, as a society, are in need of those fields’ contributions to creating the desired “global citizen.”

Historical knowledge plays an important role in the international business field. Ironically, as programs in the humanities are forced to justify their relevance to administrators, elected officials, and the general public, we, as a society, are in need of those fields’ contributions to creating the desired “global citizen.” Almost all university presses prefer to first receive a proposal from a potential author, rather than a full manuscript. Alas, no editor anywhere has the time to read the huge number of manuscripts that come our way, and the situation would be even worse if we attempted to read manuscripts from every potential author seeking a publisher. This makes the proposal an ideal introduction to a topic and a crucial step in the process towards publication. Although an author may have chatted with an editor prior to submitting a proposal (if not then I urge you to get to an academic conference and chat up editors in the exhibit hall), the proposal is the first formal representation of a book project from the author to the publisher.

Almost all university presses prefer to first receive a proposal from a potential author, rather than a full manuscript. Alas, no editor anywhere has the time to read the huge number of manuscripts that come our way, and the situation would be even worse if we attempted to read manuscripts from every potential author seeking a publisher. This makes the proposal an ideal introduction to a topic and a crucial step in the process towards publication. Although an author may have chatted with an editor prior to submitting a proposal (if not then I urge you to get to an academic conference and chat up editors in the exhibit hall), the proposal is the first formal representation of a book project from the author to the publisher.

How does one select a sampling of dozens of pairs of eighteenth-century shoes and translate the assemblage into a coherent museum exhibit housed in one charming, but tiny gallery? How does one translate a five-year study of eighteenth-century consumption patterns, cultural diffusion, and gentility in the Atlantic shoe trade into a show that will excite the imaginations of early Atlantic scholars yet appeal to the general public? How does present a material culture and fashion history exhibition in a refined Athenaeum situated in a corner of New Hampshire?

How does one select a sampling of dozens of pairs of eighteenth-century shoes and translate the assemblage into a coherent museum exhibit housed in one charming, but tiny gallery? How does one translate a five-year study of eighteenth-century consumption patterns, cultural diffusion, and gentility in the Atlantic shoe trade into a show that will excite the imaginations of early Atlantic scholars yet appeal to the general public? How does present a material culture and fashion history exhibition in a refined Athenaeum situated in a corner of New Hampshire?

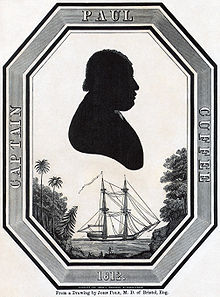

Credit cards, electronic banking, online shopping, and a host of other modern forms of commerce did not exist at the turn of the nineteenth century. Merchants throughout the Atlantic relied on reputation and good character when determining a customer’s credit worthiness. Not exactly a foolproof way to do business but seemingly less risky than our fully electronic world of money and banking in twenty-first century America. Yet, identity theft and fraud were still a part of doing business.

Credit cards, electronic banking, online shopping, and a host of other modern forms of commerce did not exist at the turn of the nineteenth century. Merchants throughout the Atlantic relied on reputation and good character when determining a customer’s credit worthiness. Not exactly a foolproof way to do business but seemingly less risky than our fully electronic world of money and banking in twenty-first century America. Yet, identity theft and fraud were still a part of doing business.