Over the past couple years, friends have asked me a lot about maps and mapping software—questions I probably have no business fielding. I’m not truly formally trained in GIS, I’ve picked up a lot of things online, from books, in workshops, but mostly through trial-and-error, and half the time I still prefer to draw my maps by hand. (Yes, I like to draw.) It’s sort of like the four-eyed leading the blind.

Over the past couple years, friends have asked me a lot about maps and mapping software—questions I probably have no business fielding. I’m not truly formally trained in GIS, I’ve picked up a lot of things online, from books, in workshops, but mostly through trial-and-error, and half the time I still prefer to draw my maps by hand. (Yes, I like to draw.) It’s sort of like the four-eyed leading the blind.

There’s a reason, though, that my friends have few other places to turn. Workshops at universities, as well as many guides online, are still largely geared towards those working on more contemporary history, and to those looking to manipulate census and other large data sets. For those of us working on colonial America—especially those working on frontiers, borderlands, and native grounds—our materials rarely support this kind of work.

As I thought about my post the last couple days, I realized I wanted to write something less to those also working on spatial-intensive projects, and something more for those—like my friends—looking to find quick and simple ways to add maps to presentations and papers. In other words, those who aren’t about to download ArcGIS, run windows on their mac, enroll in a series of workshops, lose days (weeks and months) to inputting vector and raster data, and become geospatial pros. Those who are more interested in manipulating a historic map than creating a new one from historic data. Casual mappers and prospective weekend warriors of geohistorical analysis, this is for you.

So what do you want to do?

1. You found a historic map online and now want to see it over geographic space:

1. You found a historic map online and now want to see it over geographic space:

I grabbed this map of Fort Pitt in 1761 from Historical Maps of Pennsylvania and copied the jpg url.

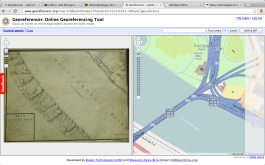

Next, I go to Georeferencer.org, which is in beta from the folks at Old Maps Online. (You’ll have to quickly register, and then you’re good to go.) I head to the homepage, submit the url of the Fort Pitt map, and hit georeference.

Next, I input the control points manually. (You can also search for specific sites and locations.) Easy enough to do. I click a point I want to reference on the Fort Pitt map—and then click the same point today on the OpenStreetMap. I do that for a few more points. (You’ll want to do this for as many points as you can verify.) Save & Exit.

Next, I input the control points manually. (You can also search for specific sites and locations.) Easy enough to do. I click a point I want to reference on the Fort Pitt map—and then click the same point today on the OpenStreetMap. I do that for a few more points. (You’ll want to do this for as many points as you can verify.) Save & Exit.

Now I’m ready to see the Fort Pitt map overlaid on real space.

It’s almost too easy. I can zoom in/out, pan around, and see how the map moves. I can open the geo-referenced Fort Pitt in Google Earth. Most importantly, I can now impress my friends and colleagues with how quickly I’ve become a hip digital humanist.

It’s almost too easy. I can zoom in/out, pan around, and see how the map moves. I can open the geo-referenced Fort Pitt in Google Earth. Most importantly, I can now impress my friends and colleagues with how quickly I’ve become a hip digital humanist.

I’m sadly not a paid spokesman (is there money in touting map software?) but I’d sing the praises of georeferencer.org all day long. It’s one of the simplest, most straight-forward and intuitive sites out there. If you encounter a map online that hasn’t already been geo-referenced (and those numbers are falling dramatically, thanks to endeavors like Old Maps Online, the British Library’s map project, Harvard’s digital maps collection, David Rumsey, and still many, many more), this should be your first stop.

2. You photographed a map in the archive and now want to see it over geographic space:

Let’s assume this is a manuscript rather than printed map. Do I have permission to reproduce this map? Would I be risking my neck by uploading it online? Am I unsure?

Let’s say I’ve contacted the archive and made sure that I do have permission. I can upload a jpg of my map to flickr or another image-sharing site. Then grab the url once it’s uploaded, and submit the url the same way on georeferencer.org as I did above. Another easy-to-use online platform I would try is MapScholar, which also lends itself very well to multimedia presentations. (I won’t reproduce the entire MapScholar guide since that’s already available on their site, but I highly recommend others seek it out.)

3. You photographed a map in the archive and now want to see it over geographic space—with an important caveat:

What if I don’t have permission? What if I only have the image for research purposes?

In that case, I’ll go offline with one of my favorite open-source platforms, QGIS. (You’ll have to download QGIS, which runs on Mac, Windows, and Linux. The ability to run natively on a Mac is another big plus. The gold-standard of GIS, esri’s ArcGIS, requires either a PC or that you run parallels/bootcamp, which is a big ask for the casual user.)

After downloading QGIS, I’ve officially crossed over from beginner recreational mapping and into the intramurals. QGIS requires more hustle on my end, but it also has many, many more payoffs.

After downloading QGIS, I’ve officially crossed over from beginner recreational mapping and into the intramurals. QGIS requires more hustle on my end, but it also has many, many more payoffs.

The next step is to activate the OpenLayers plug-in. (If you need help doing this, check out Lesson 4 under Mapping and GIS from the Programming Historian. I’d highly suggest all 4 lessons if you’re going to use QGIS.) I then open Google Satellite from OpenLayers to use as my baselayer.

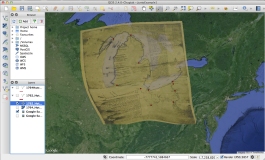

From one of my archives, I have a 1762 manuscript map of a military tour from Fort Cumberland, Maryland. I’ll open the “georeferencer” (under raster on the menu bar) and then open up the jpeg photo of the map. Remembering how I created control points with georeferencer.org, I will now do much the same. I create a new control point, click on Fort Pitt on my 1762 map, and then hit “from map canvas” on the pop-up window. This brings forward the primary QGIS window and the Google satellite map. I (zoom in and) click the same spot where Fort Pitt would be today. That control point is now set. I do the same for other forts and specific locations on my map. Save the points. (I do NOT mess with the file name or extension when I save my control points. These points will now load automatically anytime I open the 1762 map in the georeferencer.) I then hit “run” (I use thin plate spline for the transformation type, and linear for the resampling.)

My map is now georeferenced. (The red dots show where my control points were set.) Now that my map is over real space, I notice that it’s been stretched a bit. While the map still doesn’t line up perfectly—that would require many more control points—it is a pretty good approximation.

My map is now georeferenced. (The red dots show where my control points were set.) Now that my map is over real space, I notice that it’s been stretched a bit. While the map still doesn’t line up perfectly—that would require many more control points—it is a pretty good approximation.

Yes, that was a lot more work than my online options. But I promise it was worth it. Because there’s a lot more I can do with this map now.

For one, I noticed that the map included a lot of Indian roads, some connecting forts, other villages. I’d like to see those roads over the 1762 map. I trace them and get this:

The red lines show approximately where these roads ran in the Eighteenth Century. For someone like me, who writes about transportation, this is a pretty useful visual for a conference or paper. I can also lay these roads directly over the Google Satellite base layer:

I also happen to have another similar manuscript map, also from 1762, which depicts roads in the same region. How well do those match up with the roads on this map? I can georeference that map and compare.

Turns out they’re pretty darn similar. Using QGIS, I was able to quickly and easily illustrate overlapping depictions and imaginations of eighteenth-century roads. QGIS also offered a quick way to check the relative (very, very relative) accuracy of the maps. These maps might have been off in terms of the precise routes of eighteenth-century roads and paths, but I can now feel a little more confident—after cross-referencing against my manuscript sources—that some major roads at least approximated these.

There are many more ways to use geospatial software, and many more platforms to do it. I’d love to hear from others working on spatial projects about what programs you prefer and what your various experiences have been. For those who’ve dabbled, your experiences with maps and map software would also be a huge help. Finally, any suggestions to add to this working list of free open-source applications and sites are especially welcome:

Reblogged this on DailyHistory.org and commented:

Alyssa Zuercher Reichardt discusses how early American historians can use Basic GIS to help scholars either manipulate “a historic map” or create a new one from “historic data.” I have never used maps in my research, but I am floored by some of the possibilities available to historians. If you work with maps you definitely should read her post because she shows you how to lay a historic map over a contemporary geographic space.

There’s also Harvard’s WorldMap http://worldmap.harvard.edu/, which lets you georeference maps as well as upload or use other kinds of data and host exhibits. (These aren’t mine, but here’s a couple of early America examples: http://worldmap.harvard.edu/maps/2025; http://worldmap.harvard.edu/maps/early_historical_growth_baltimore). WorldMap also allows you to grab the WMS of a georeferenced map for use in Neatline as well.

The new Palladio http://palladio.designhumanities.org/#/ has mapping functionality also if you have data but no historic map.

Reblogged this on Christopher P. Sawula.

Pingback: The Junto Enters the Terrible Twos! « The Junto

There is also another free tile mapping site you can use to scan and upload your maps to called Mapc2Mapc for free or very little money depending on your map size.

Good article,

Jason Hodges

http://www.AgTerra.com/mapitfast

Thanks so much, Alyssa! This is really helpful.

Pingback: The Many & the One « The Junto

Pingback: Ashley Sanders: DH Reading Group | claremontdh.com

Pingback: Intro to DH Short Course | Ashley R. Sanders