Last semester, I taught my first section of Digital History, following my participation in the 2016 NEH Doing Digital History Institute. The program, which is headed by Sharon Leon and Sheila Brennan of George Mason University’s Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, is designed for mid-career historians who come from institutions with little infrastructure or support for DH professional development. Owing to my library science background, I came to the Institute with a strong technological background, but the two weeks I spent in Arlington, Virginia last July definitely made me rethink my approach to digital history pedagogy. Continue reading

Last semester, I taught my first section of Digital History, following my participation in the 2016 NEH Doing Digital History Institute. The program, which is headed by Sharon Leon and Sheila Brennan of George Mason University’s Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, is designed for mid-career historians who come from institutions with little infrastructure or support for DH professional development. Owing to my library science background, I came to the Institute with a strong technological background, but the two weeks I spent in Arlington, Virginia last July definitely made me rethink my approach to digital history pedagogy. Continue reading

Category Archives: Pedagogy

Women’s History, Primary Sources, and the United States History Survey

Abigail Adams (Source)

“What did you find surprising about this source?” It was Week Nine of the fall semester, when the students in my United States History to 1877 survey course were worn down by too many midterms and too little sleep. I was attempting to spark conversation about the day’s assigned primary source, the late-eighteenth-century journal of Mary Dewees, a Philadelphia woman who moved west to Kentucky. Surely, I thought, some of my students would have been surprised to read a woman’s firsthand account of crossing rivers and mountains as she took part in white trans-Appalachian migration and the resulting displacement of Native Americans from their lands. Continue reading

Monographs in the Survey: Strategies for Writing Across the Curriculum

I am fortunate that in graduate school, I had quite a bit of guidance in writing across the curriculum pedagogy. I have since taught approximately a dozen designated writing-intensive courses. Most history courses are writing-intensive by default, and many history faculty do find themselves teaching writing and research techniques. Here, I am focusing primarily on the strategies I use in survey courses, with a short list of monographs that I have found work well for this purpose.

I am fortunate that in graduate school, I had quite a bit of guidance in writing across the curriculum pedagogy. I have since taught approximately a dozen designated writing-intensive courses. Most history courses are writing-intensive by default, and many history faculty do find themselves teaching writing and research techniques. Here, I am focusing primarily on the strategies I use in survey courses, with a short list of monographs that I have found work well for this purpose.

Guest Post: Dr. Strangehonor, Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Snapchat

Today’s guest post is by Honor Sachs, an assistant professor of history at Western Carolina University and author of Home Rule: Households, Manhood, and National Expansion on the Eighteenth-Century Kentucky Frontier.

Several years ago, I attended a seminar on digital pedagogy. I thought it might be worthwhile to explore new opportunities out there for social media in the classroom. It was indeed an eye-opening experience, though not in the way I had hoped. Seminar leaders regaled us with software package after software package filled with whistles, bells, alerts, gimmicks, everything, they claimed, one would need to connect with this generation of “digital natives” (their term, not mine.) Students these days spend so much time on social media, they claimed, that faculty need to learn to connect with them online in order to really engage. “Here’s a program that allows you to text your students!” “Here’s another that allows you to collect data on how much time your students spend on homework!” “Here’s a program where you can instant message your student and remind them to study!” Continue reading

Several years ago, I attended a seminar on digital pedagogy. I thought it might be worthwhile to explore new opportunities out there for social media in the classroom. It was indeed an eye-opening experience, though not in the way I had hoped. Seminar leaders regaled us with software package after software package filled with whistles, bells, alerts, gimmicks, everything, they claimed, one would need to connect with this generation of “digital natives” (their term, not mine.) Students these days spend so much time on social media, they claimed, that faculty need to learn to connect with them online in order to really engage. “Here’s a program that allows you to text your students!” “Here’s another that allows you to collect data on how much time your students spend on homework!” “Here’s a program where you can instant message your student and remind them to study!” Continue reading

America, the Series?

It took me a few days to realise my mistake. Around the third week of the semester, in this my first year teaching the “Foundations of American History” survey course here at Birmingham, I slipped up in a way I’d never have imagined. I was lecturing about Bacon’s Rebellion, and about Stephen Saunders Webb’s provocative, half-mad 1676: The End of American Independence. I found it odd that my students didn’t seem to see what was so funny, or at least glib, about Webb’s title. Those blank looks spooked me. So I said, “well, you know guys, because, 1776, right? That’s… when the Americans declared independence? Remember?” Continue reading

It took me a few days to realise my mistake. Around the third week of the semester, in this my first year teaching the “Foundations of American History” survey course here at Birmingham, I slipped up in a way I’d never have imagined. I was lecturing about Bacon’s Rebellion, and about Stephen Saunders Webb’s provocative, half-mad 1676: The End of American Independence. I found it odd that my students didn’t seem to see what was so funny, or at least glib, about Webb’s title. Those blank looks spooked me. So I said, “well, you know guys, because, 1776, right? That’s… when the Americans declared independence? Remember?” Continue reading

Guest Post: “Have You Read this?:” Teaching About Early Republic Print Culture with Hamilton

We are pleased to share this guest post from Michelle Orihel, an Assistant Professor of History at Southern Utah University. Dr. Orihel received her doctorate from Syracuse University and is currently working on a book manuscript about Democratic-Republican Societies in the post-revolutionary period.

Last spring, I blogged about how I used the song “Farmer Refuted” from Hamilton: An American Musical to teach about the pamphlet wars of the American Revolution.[1] But, that’s not the only song about pamphlets in the musical. There’s also “The Reynolds Pamphlet,” named after the sensational tract published in 1797 in which Alexander Hamilton confessed to adultery.[2]

Last spring, I blogged about how I used the song “Farmer Refuted” from Hamilton: An American Musical to teach about the pamphlet wars of the American Revolution.[1] But, that’s not the only song about pamphlets in the musical. There’s also “The Reynolds Pamphlet,” named after the sensational tract published in 1797 in which Alexander Hamilton confessed to adultery.[2]

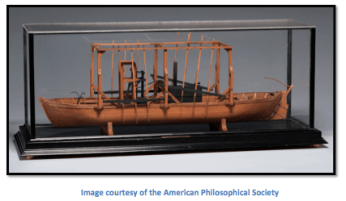

Steamboats and Teaching Tech

Steamboats are ready for a comeback. A pedagogical one, that is. While in all likelihood the steamboat’s time as a common form of transportation in the United States is finished, over the past several weeks I’ve noticed subtle mentions in a seminar paper, a museum display, comments during last month’s PEAES conference, and only once, I should add, did I bring them up! This may be in part due to my increasing interest in them as a pivotal subject in the history of Anglo-American intellectual property. Yet I don’t think this is entirely an instance of frequency illusion but rather indicates that while steamboats are no longer an effective mode of movement, they are very effective as an illustrative one, particularly when trying to flesh out broader themes in the political economy of the Early Republic. Continue reading

Steamboats are ready for a comeback. A pedagogical one, that is. While in all likelihood the steamboat’s time as a common form of transportation in the United States is finished, over the past several weeks I’ve noticed subtle mentions in a seminar paper, a museum display, comments during last month’s PEAES conference, and only once, I should add, did I bring them up! This may be in part due to my increasing interest in them as a pivotal subject in the history of Anglo-American intellectual property. Yet I don’t think this is entirely an instance of frequency illusion but rather indicates that while steamboats are no longer an effective mode of movement, they are very effective as an illustrative one, particularly when trying to flesh out broader themes in the political economy of the Early Republic. Continue reading

Guest Post: Nate Parker’s Birth of a Nation (2016) in the Classroom

Today’s guest poster, Stephanie J. Richmond, is an Assistant Professor and coordinator of history programs at Norfolk State University in Norfolk, VA. She is a historian of gender and race in the Atlantic World. The following review contains spoilers and discussion of sexual assault.

Many historians of race and slavery in early America were very excited when the wide release of Nate Parker’s new film on the Nat Turner rebellion was announced following its rave reviews at last year’s Sundance Film Festival. With the recent surge in Hollywood depictions of slavery (12 Years a Slave, WGN’s series Underground, and even Django Unchained), films have become an important part of teaching African American history. The best of these films and tv series give students an understanding of the psychological impact of slavery on both enslaved and free African Americans, illustrating many of the tactics of control and exploitation discussed in textbooks and classrooms. I had the opportunity to see the pre-release version of the film in April 2016 when Parker’s production company held screenings for HBCU faculty in several cities around the country. Several colleagues and I attended the screening and got our first glimpse at Parker’s version of a history that is both local and national. After the screening, production assistants recorded our reactions to the film, and took detailed notes on our critiques of the film both as a work of popular entertainment and its historical inaccuracies and misrepresentations, of which there were many. My own feelings on the film and its usefulness in the classroom are complicated and have changed significantly since my first viewing of the film in April. (In full disclosure, I have seen the film twice, both times at events put on by Parker’s production company).

Many historians of race and slavery in early America were very excited when the wide release of Nate Parker’s new film on the Nat Turner rebellion was announced following its rave reviews at last year’s Sundance Film Festival. With the recent surge in Hollywood depictions of slavery (12 Years a Slave, WGN’s series Underground, and even Django Unchained), films have become an important part of teaching African American history. The best of these films and tv series give students an understanding of the psychological impact of slavery on both enslaved and free African Americans, illustrating many of the tactics of control and exploitation discussed in textbooks and classrooms. I had the opportunity to see the pre-release version of the film in April 2016 when Parker’s production company held screenings for HBCU faculty in several cities around the country. Several colleagues and I attended the screening and got our first glimpse at Parker’s version of a history that is both local and national. After the screening, production assistants recorded our reactions to the film, and took detailed notes on our critiques of the film both as a work of popular entertainment and its historical inaccuracies and misrepresentations, of which there were many. My own feelings on the film and its usefulness in the classroom are complicated and have changed significantly since my first viewing of the film in April. (In full disclosure, I have seen the film twice, both times at events put on by Parker’s production company).

Making Students Lead Discussion: Three Methods

Image credit: legogradstudent.tumblr.com

I wrote lots of recommendation letters for students this summer, probably because last year was the first year that I taught students in their final undergraduate year, and many of them are looking for or have recently found jobs. I always die a little inside when I read or hear the word “employability,” because I think it’s a jargony term that seems to reiterate the point that a university sells a degree to its customers, the students. I do not think that education should be viewed as such a service, but neither do I think that it’s responsible to entirely eschew discussions of marketable skills that students can mention in their pre- and post-graduate job searches. Not all of them will become professional historians, and given the state of the academic job market, that’s okay! I spend time at the start of each term, in class and in my syllabi, explaining why I think it’s important for students to participate in class discussion. One of my key points is that a student’s class contributions are something that I can and do mention in my recommendation letters. Having spent the summer writing letters for recent graduates I know that I’ve mentioned their contributions in every single letter I’ve written. Lately, my feelings have gone beyond believing that students should participate: I think students should lead discussion. Continue reading

Making Utopia a Theme in Early American History

This year I’m overhauling my early American survey course. Not only do I need to make it fit the schedule at my new institution, but because I’m planning to be teaching here for quite a while, I also want to build a course that carries my own signature, and where I can work out some of my own questions and ideas. Survey courses that I’ve taught before—like the one designed by Sarah Pearsall for Oxford Brookes University—have been themed around the violence of empire and slavery. Obviously, those continue to be both central concerns in teaching and the foci of cutting-edge scholarship. But in my search for something different, and for something that might capture the imaginations of my first-year students, I’ve chosen a different path: utopia. Continue reading

This year I’m overhauling my early American survey course. Not only do I need to make it fit the schedule at my new institution, but because I’m planning to be teaching here for quite a while, I also want to build a course that carries my own signature, and where I can work out some of my own questions and ideas. Survey courses that I’ve taught before—like the one designed by Sarah Pearsall for Oxford Brookes University—have been themed around the violence of empire and slavery. Obviously, those continue to be both central concerns in teaching and the foci of cutting-edge scholarship. But in my search for something different, and for something that might capture the imaginations of my first-year students, I’ve chosen a different path: utopia. Continue reading