The Open Syllabus Project (@opensyllabus) has collected “over 1 million syllabi” in the hopes of determining “how often texts are taught” and “what’s taught with what.” They hope their project will provide “a promising means of exploring the history of fields, curricular change, and differences in teaching across institutions, states, and countries.” The OSP has released a beta version of their “Syllabus Explorer,” which “makes curricula visible and navigable in ways that we think can become valuable to authors, teachers, researchers, administrators, publishers, and students.” Intrigued that the project claims to have catalogued the assigned readings from 460,760 History syllabi, I went through the list to find the most assigned works of early American history. Continue reading

The Open Syllabus Project (@opensyllabus) has collected “over 1 million syllabi” in the hopes of determining “how often texts are taught” and “what’s taught with what.” They hope their project will provide “a promising means of exploring the history of fields, curricular change, and differences in teaching across institutions, states, and countries.” The OSP has released a beta version of their “Syllabus Explorer,” which “makes curricula visible and navigable in ways that we think can become valuable to authors, teachers, researchers, administrators, publishers, and students.” Intrigued that the project claims to have catalogued the assigned readings from 460,760 History syllabi, I went through the list to find the most assigned works of early American history. Continue reading

Tag Archives: teaching

Can Class Participation Be Taught?

Class participation has bothered me since I graded a set of midterm exams from my first solo-taught course. As I sat down to read through those signature blue books, I felt anxious about how my students would perform. Had they learned anything? Did the lectures thus far sink in at all? To gauge the potential quality of the exams, I scanned through some of the responses of my “better” students and felt fairly confident grading the rest.

At the end of the stack, however, I came across an exam that has stuck with me. The student in question had me worried all semester. Not only did this student refuse to participate in class discussions but she frequently looked irritated whenever I asked the class a question that wasn’t rhetorical. Continue reading

Teaching History Without Chronology

Most history courses follow a relatively simple formula: take a geographic space X, select a time span from A to B, add topics, and you’ve got yourself a course. It varies, of course, but works for both introductory courses, where you might survey the political, social, and cultural development of the people living in a geographic area, to upper-level courses with topical focuses. As a field whose primary concern is change over time, that formula makes sense. That consistency also means that students expect it from their high school and college history courses. And how else would you organize a history course?

Most history courses follow a relatively simple formula: take a geographic space X, select a time span from A to B, add topics, and you’ve got yourself a course. It varies, of course, but works for both introductory courses, where you might survey the political, social, and cultural development of the people living in a geographic area, to upper-level courses with topical focuses. As a field whose primary concern is change over time, that formula makes sense. That consistency also means that students expect it from their high school and college history courses. And how else would you organize a history course?

I found out last semester.

The Revolution Will Be Live-Tweeted

As many of our readers already know, this fall has marked the 250th anniversary since the protests against the Stamp Act, one of the earliest major actions of the imperial crisis that resulted in the American Revolution. Over the course of a year—from the first arrival of the Act in May 1765 until news of its repeal arrived in May 1766—colonists in the “thirteen original” colonies (as well as the “other thirteen”) passed resolutions, argued in essays, marched in the streets, forced resignations, and otherwise made clear their displeasure with paying a tax on their printed goods.

As many of our readers already know, this fall has marked the 250th anniversary since the protests against the Stamp Act, one of the earliest major actions of the imperial crisis that resulted in the American Revolution. Over the course of a year—from the first arrival of the Act in May 1765 until news of its repeal arrived in May 1766—colonists in the “thirteen original” colonies (as well as the “other thirteen”) passed resolutions, argued in essays, marched in the streets, forced resignations, and otherwise made clear their displeasure with paying a tax on their printed goods.

Early America Comic Con: Drawing the American Revolution

“Welders make more money than philosophers,” Marco Rubio said in a recent G.O.P. debate. “We need more welders and less philosophers,” he continued, proudly. It was a decent line from the presidential hopeful. But not long after these words echoed around the Milwaukee Theatre, it was shown to be a somewhat clumsy statement, not least when seen alongside figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (comparative wages: philosophers & welders). Thus over the days following Rubio’s line, it was caricatured, with one cartoonist picking up on Rubio’s wording. This G.O.P. presidential candidate is not alone: All of the 2016 presidential candidates, Democrat and Republican, have been caricatured. So, too, are their worldwide equivalents on a regular basis. Continue reading

Guest Post: Revisiting Women of the Republic with Linda Kerber at the American Antiquarian Society

Carl Robert Keyes is an Associate Professor of History at Assumption College in Worcester, Massachusetts. He recently launched the #Adverts250 Project, featuring advertisements published 250 years ago in colonial American newspapers accompanied by brief commentary, via his Twitter profile (@TradeCardCarl).

My Revolutionary America class recently visited the American Antiquarian Society for a behind-the-scenes tour followed by a document workshop in the Council Room. As we passed through the closed stacks I remarked to one of the curators, “This still blows me away, yet nothing can compare to the first time I came back here. Taking this all in for the first time is an experience that cannot be re-created.”

My Revolutionary America class recently visited the American Antiquarian Society for a behind-the-scenes tour followed by a document workshop in the Council Room. As we passed through the closed stacks I remarked to one of the curators, “This still blows me away, yet nothing can compare to the first time I came back here. Taking this all in for the first time is an experience that cannot be re-created.”

The Wandering Essay: A Lesson Plan for Teaching Writing

Image by Zazzle.com

Before I even started teaching I knew that one of the most difficult parts of the job would be teaching writing. It’s not that I consider myself a great writer; I know I’m prone to tangents, and I’ve never met a dash, comma, or semi-colon I didn’t want to use. It’s just that I find writing pretty intuitive. For informal pieces like this one, I tend to write the way that I talk, and for more structured academic writing my first drafts are pretty crappy—but they get written and then ironed out in my editing process. The takeaway here is that I’ve had to think hard about how to teach writing because the process of writing isn’t really one that I had to articulate before I had students. Knowing that many of you are almost ready to collect first essay assignments, I thought I’d talk a bit today about how we teach writing to students. My Wandering Essay lesson plan is one of the meanest, most productive approaches I’ve used because it makes clear the fact that writing is a process. Here’s how you do it: Continue reading

Putting the “Pop” into Popular History: Pop Culture Videos in the Classroom

President Kanye West may never become a reality, but I’d like to think he’d choose a Secretary of Education who’d endorsed creative pedagogy.

Kanye West’s presidential ambitions remind us that American history is full of fun surprises—even if most of them are short-lived and forgettable. Although it’s probably too much of a stretch to make the entertainment of #Kanye2020 relevant to American history—though Donald Trump’s candidacy perhaps proves that nothing is outside the realm of possibility—I do love to find pop culture references and videos and bring relevance to what students might see as staid topics.

I’m declaring this post a judgment-free zone so that I can be frank: I have a tough time keeping the attention of the freshmen students in my undergraduate survey class. But I have found that one thing that works well is video clips, and so I find myself drawing from youtube nearly as much as I do from powerpoint. Luckily, I’m a TV-show junkie, and so I have have a lot of background at my disposal. (Finally a way to justify my Netflix binges!) Indeed, my use of videos in class is one of the constant positives in my students’ evaluations, so I know it’s not just me who enjoys this approach. Continue reading

Digital Pedagogy Roundtable, Part 1: Students’ Access to Sources

This week, The Junto will feature a roundtable on digital pedagogy, in which we discuss our different approaches to using digital sources in the classroom. Today, Rachel Herrmann talks about the challenge of access. Jessica Parr, Joseph Adelman, and Ken Owen will also contribute.

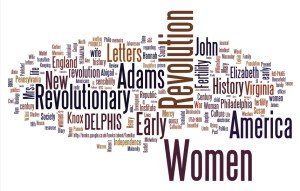

A Wordle made from sources my undergraduates located for our in-class source-finding competition

Let me preface this post by saying that I’d hesitate to call myself a digital humanist; I don’t code or map or mine texts. As Lincoln Mullen pointed out a while back, however, digital practices exist on a spectrum. There are some things I do for my own research and in the classroom—tweeting, running my department’s social media accounts, using Amazon’s “Look Inside” feature to chase up a footnote so as not to use up one of my precious Interlibrary Loan requests, and of course, blogging for The Junto—that digital humanists also do. These approaches have been helpful in my teaching for three problems related to access to sources. Continue reading

Graphic Novels in the Classroom

This week we’ve discussed the graphic novels as historical fiction, the strengths of using graphic novels to discuss fraught material, and complex process of adapting historical research to sequential art. We would like to end our roundtable discussing more broadly the possibilities of using graphic novels in the classroom.

This week we’ve discussed the graphic novels as historical fiction, the strengths of using graphic novels to discuss fraught material, and complex process of adapting historical research to sequential art. We would like to end our roundtable discussing more broadly the possibilities of using graphic novels in the classroom.

The first strength of graphic novels is their novelty. Assigning works like Kyle Baker’s Nat Turner or Fetter-Vorm and Kelman’s Battle Lines is a surprise to most students. By not being another monograph or set of primary sources, graphic novels shake up a syllabus. This is good for students, who may be interested in exploring a subject in a more unconventional way, and for teachers, for it forces us to reconsider how to teach subjects we may have taught many, many times. This novelty also adds some additional accessibility for students who might be skeptical of reading more traditional assignments. Continue reading