Thanks to John Fea’s live-tweeting and subsequent reflections on OAH panels this past weekend, I would like to address some of the points and comments made during the panel entitled, “State of the Field: The Trans-Atlantic Enlightenment in America.” Since Twitter is problematic in getting across complex ideas due to its 140-character limitation, I have chosen a few of the tweets in which the comments seemed to me to be common arguments or perceptions that I have previously encountered.

Thanks to John Fea’s live-tweeting and subsequent reflections on OAH panels this past weekend, I would like to address some of the points and comments made during the panel entitled, “State of the Field: The Trans-Atlantic Enlightenment in America.” Since Twitter is problematic in getting across complex ideas due to its 140-character limitation, I have chosen a few of the tweets in which the comments seemed to me to be common arguments or perceptions that I have previously encountered.

Author Archives: Michael D. Hattem

The JuntoCast, Episode 9: The Early American Presidency

In honor of President’s Day, this month’s episode features Ken Owen, Michael Hattem, and Roy Rogers discussing issues related to the development of the Presidency in the early republic, including the initial defining of the office by Federalists and John Adams’ and Thomas Jefferson’s challenges in navigating that office, as well as the role of the Presidency in public memory. Continue reading

In honor of President’s Day, this month’s episode features Ken Owen, Michael Hattem, and Roy Rogers discussing issues related to the development of the Presidency in the early republic, including the initial defining of the office by Federalists and John Adams’ and Thomas Jefferson’s challenges in navigating that office, as well as the role of the Presidency in public memory. Continue reading

On Undergraduate Writing

I am currently in the midst of grading midterms and the process, as well as a recent piece by Marc Bousquet at CHE, has gotten me thinking about undergraduate writing and the debate of its value kicked off by Rebecca Schuman’s piece, “The End of the College Essay,” in Slate back in December. I want to use my post today to lay out some thoughts I have been having about undergraduate writing in lieu of the debate these articles have occasioned. Continue reading

I am currently in the midst of grading midterms and the process, as well as a recent piece by Marc Bousquet at CHE, has gotten me thinking about undergraduate writing and the debate of its value kicked off by Rebecca Schuman’s piece, “The End of the College Essay,” in Slate back in December. I want to use my post today to lay out some thoughts I have been having about undergraduate writing in lieu of the debate these articles have occasioned. Continue reading

The Week in Early American History

On to this week’s links…

On to this week’s links…

A Long Time Ago in an Archive Far, Far Away

Michael D. Hattem continues our roundtable on James Merrell’s article, “‘Exactly as they appear’: Another Look at the Notes of a 1766 Treason Trial in Poughkeepsie, New York, with Some Musings on the Documentary Foundations of Early American History” from the most recent issue of Early American Studies.

Some of our (very) regular readers will know that I have a penchant for occasionally adopting a bit of the role of contrarian. For me, it serves as a way to shake myself into thinking differently about something, and I would hope it does the same for the reader. For this roundtable, it could have been quite easy to sing the praises of Dr. Merrell’s excellent article, and go on a 500-word rant about why historians should always seek out the manuscript sources over older published collections. However, I think my slot in this roundtable is an excellent opportunity to try to approach the article differently, one that attempts to historicize its meta-argument from a documentary editing perspective. Continue reading

Guest Post: Sir James Wright and Jenny, his free “black servant”

Today’s guest poster is Greg Brooking (PhD, Georgia State University). His dissertation on Sir James Wright, royal governor of Georgia, is entitled, “‘My zeal for the real happiness of both Great Britain and the colonies’: The Conflicting Imperial Career of Sir James Wright.” He is the recipient of two fellowships from the David Library of the American Revolution and authored a chapter in General Nathanael Greene and the American Revolution in the South (University of South Carolina Press, 2012). He currently teaches at Kennesaw State University and Southern New Hampshire University. This is his first guest post for The Junto.

I’ve just begun the arduous task of transforming my recently completed dissertation about colonial and revolutionary Georgia into a work worthy of an academic press. Part of this process, for me at least, has been to re-examine my notecards (actually an enormous Excel spreadsheet), seeking new gems, ideas, and angles. In so doing, I’ve rediscovered a tidbit that I want to further develop during the manuscript process and I humbly submit this post as a solicitation to the blog’s readers, seeking their varied and expert insights. Specifically, this tidbit relates to a caveat in the final will and testament of Sir James Wright (1716-1785), which calls for an annuity for his free “black servant,” Jenny. Continue reading

I’ve just begun the arduous task of transforming my recently completed dissertation about colonial and revolutionary Georgia into a work worthy of an academic press. Part of this process, for me at least, has been to re-examine my notecards (actually an enormous Excel spreadsheet), seeking new gems, ideas, and angles. In so doing, I’ve rediscovered a tidbit that I want to further develop during the manuscript process and I humbly submit this post as a solicitation to the blog’s readers, seeking their varied and expert insights. Specifically, this tidbit relates to a caveat in the final will and testament of Sir James Wright (1716-1785), which calls for an annuity for his free “black servant,” Jenny. Continue reading

The JuntoCast, Episode 8: Thomas Paine and “Common Sense”

In this month’s episode, Ken Owen, Michael Hattem, Roy Rogers, and Ben Park discuss Thomas Paine, including reconsidering the importance of his most famous work, “Common Sense,” his life as an eighteenth-century transatlantic radical, and his legacy today compared to that of the other “founders.”

In this month’s episode, Ken Owen, Michael Hattem, Roy Rogers, and Ben Park discuss Thomas Paine, including reconsidering the importance of his most famous work, “Common Sense,” his life as an eighteenth-century transatlantic radical, and his legacy today compared to that of the other “founders.”

You can click here to listen to the mp3 in a new window or right-click to download and save for later. You can also subscribe to the podcast in iTunes. We would greatly appreciate it if our listeners could take a moment to rate or, better yet, review the podcast in iTunes. As always, any and all feedback from our listeners is greatly welcomed and appreciated.

The Week in Early American History

Looking Less Backward: Ten (Relatively) Recent Books That Anyone Interested In Early American History Should Read

The day after Christmas, The New Republic published a piece by Senior Editor, John J. Judis, entitled “Looking Backward: Ten Books Any Student of American History Must Read.” The piece began promisingly (flatteringly, even): “I woke up on Christmas morning thinking about American historians.” [Editor’s Note: Wouldn’t the world be a better place if more people did that?] Judis closed the opening paragraph with the following caveat: “They’re my favorites; they’re not the best books.” Each book was followed by a paragraph with some combination of a brief synopsis and Judis’s own reactions. I have linked to the article but, just for reference, I’ll list his ten picks here: Continue reading

The “War on Christmas” in Early America

With Christmas right around the corner, we are re-posting this piece from three years ago. All of us at The Junto would like to wish happy holidays to all our readers.

As an historian of early America, I suspect I am not alone in sighing a little bit to myself when hearing the often heated rhetoric about the “War on Christmas” emanating from right-wing and evangelical media outlets at this time of the year. That, of course, is because the real war on Christmas was not waged by 21st-century godless, liberal secular humanists and the ACLU but by 17th-century New England Puritans, particularly the clergy.

Saturnalia was a pagan Roman festival held annually from December 17-25. Its customary celebrations were both chaotic and violent and, hence, were popular amongst lower-class Romans. In the fourth century, as the Catholic Church sought to bring the pagan masses into the Christian fold, the Church adopted the final day of the festival as Jesus’s birthday, which the New Testament does not indicate and on which, until this time, there had been no widespread consensus. The Church effectively killed two birds with one stone. Throughout the centuries, the most violent aspects of the celebration (which, allegedly, may have included human sacrifices) fell away, but the customs of near-lawless revelry persisted, and indeed defined the celebrations in the early modern period.

At the start of the early modern period, the holiday was not yet the priority it has become, as Easter dominated the Catholic calendar. But the Reformation had a significant impact on the perception of Christmas, both positively and negatively. The holiday celebration customs were continued by the Church of England. The often uninhibited revelry of the holiday (which Puritans derisively referred to as “Foolstide”) appealed to the English lower classes while the gentry celebrated with “eating and drinking, [and] banqueting and feasting.”

In addition there was a distinct class aspect to one of the customs, in which the poorest man in the town was named “The Lord of Misrule” and treated like a gentleman.[1] Another custom, known as “wassailling” involved lower-class persons going to the homes of wealthy individuals and “asking” for food and drink, which they would then use to toast that individual. Due to the penchant for disorder, immodesty, gluttony, and the (temporary) breakdown of the social order, it should come as no surprise that in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, English dissenters began to take a very dim view of the holiday. Indeed, the hotter the Protestant, the stronger the aversion to Christmas. But their opposition to Christmas was not just due to the overtly social nature of its celebration. Puritan faith derived wholly from scripture, and, in 1645 and again in 1647, the Long Parliament declared the abolition of all holy days except the Sabbath, which was the only day described as such in the Bible.[2]

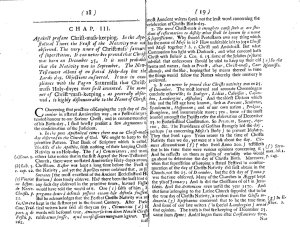

And so the first English dissenters who settled New England in the early seventeenth century were, like their brethren back home, decidedly anti-Christmas. Puritans were keenly aware of the holiday’s pagan origins, as Increase Mather wrote in A Testimony against Several Prophane and Superstitious Customs, Now Practiced by Some in New England: [3]

In the pure Apostolical times there was no Christ-mass day observed in the Church of God. We ought to keep the primitive Pattern. That Book of Scripture which is called The Acts of Apostles saith nothing of their keeping Christ’s Nativity as an Holy-day.

[. . .]

Why should Protestants own any thing which has the name of Mass in it? How unsuitable is it to join Christ and Mass together? [. . .] It can never be proved that Christ’s nativity was on 25 of December.

[. . .]

[They] who first of all observed the Feast of Christ’s Nativity in the latter end of December, did it not as thinking that Christ was born in that Month, but because the Heathens’ Saturnalia was at that time kept in Rome, and they were willing to have those Pagan Holidays metamorphosed into Christian ones.

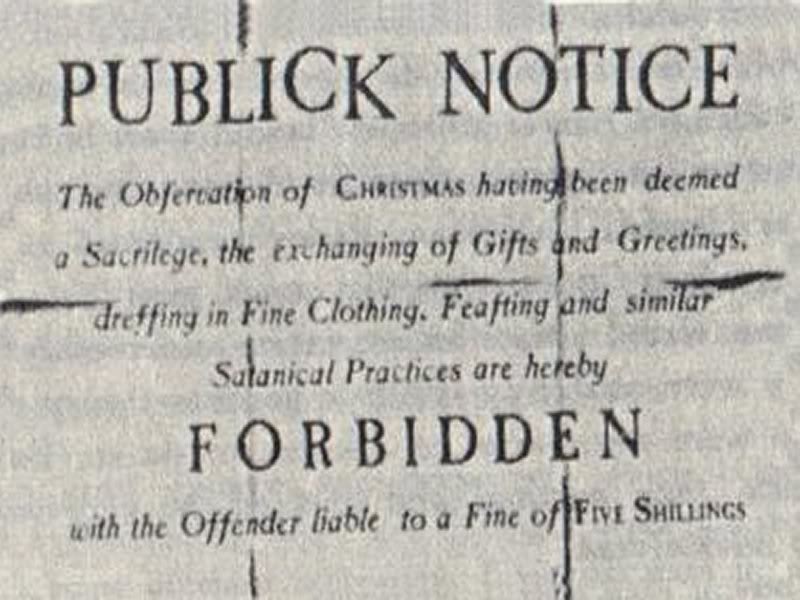

By mid-century, the Puritan “City on a Hill” was already losing its spiritual homogeneity and the combination of new settlers and a new generation less committed to Puritan strictures forced the Massachusetts General Court to take action. On May 11, 1659, the following was entered into the General Court’s records:[4]

For preventing disorders, arising in several places within this jurisdiction by reason of some still observing such festivals as were superstitiously kept in other communities, to the great dishonor of God and offense of others: it is therefore ordered by this court and the authority thereof that whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way, upon any such account as aforesaid, every such person so offending shall pay for every such offence five shilling as a fine to the county.

Despite being told to repeal the “penalty for keeping Christmas” as early as May of 1665 for its “being directly against the lawe of England,” the law was not stricken until 1681, followed by renewed pressure from Charles II.[5] But even though the legal war was over, the cultural war on Christmas continued. In 1686, the unpopular royal governor of the new Dominion of New England, Sir Edmund Andros, required an armed escort at a Christmas service he sponsored (somewhat brazenly) in Boston. Indeed, Christmas was not celebrated widely in New England through the eighteenth century, and, when it was, it was done privately. All this is not to imply that Christmas was celebrated broadly outside of New England. Even after the Revolution, the Congress was known to meet on Christmas Day, if they were in session. Throughout the nineteenth century, as well, there are numerous reports from all over the United States attesting to the lack Christmas observance, particularly by various Protestant and German Pietist sects.

A few days ago, Bill O’Reilly claimed that—thanks to him and Fox News—the “War on Christmas” had been won and Christmas had been saved for all the true Americans out there wishing to celebrate the “traditional American Christmas.” However, the history shows that waging a “war on Christmas” is one of the very oldest of all American traditions and is a far more American tradition than the current twentieth-century, commercial capitalist version of Christmas that Bill O’Reilly claims to have saved.

____________________

[1] This tradition had its roots in a Saturnalian custom of Masters exchanging roles with their servants.

[2] If there could be said to have been a war “over” Christmas, it would have been in the 1640s and 1650s as Oliver Cromwell and Parliament tried to enforce their ban on Christmas by attempting to stop public celebrations by Anglicans (and the few remaining Catholics) and force shop keepers to remain open. In many localities, the result was fighting in the street between the authorities and those intent on celebrating the holiday in its traditional manner. For more on the English context, see Chris Durston, “The Lords of Misrule: The Puritan War on Christmas, 1642-60” History Today 35, no. 12 (1985).

[3] Increase Mather, A Testimony against Several Prophane and Superstitious Customs, Now Practiced by Some in New England (London, 1687), 18-9; 35. Early English Books Online.

[4] Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England, 5 vols., ed. Nathaniel B. Shurtleff (Boston: From the Press of W. White, printer to the Commonwealth, 1854), 4:366.

[5] Ibid., 5:212; For repeal, see William H. Whitmore, A Bibliographical Sketch of the Laws of the Massachusetts Colony from 1630 to 1686 (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, City Printers, 1890), 126.