Earlier this week, the University of Maryland and their athletic uniform supplier, Under Armour, announced that the university’s football team “will wear football uniforms inspired by the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Baltimore and the writing of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ when it hosts West Virginia at Byrd Stadium” tomorrow, September 13.[1] The game will be played exactly 200 years to the day after Francis Scott Key penned “Defence of Fort McHenry,” a poem later set to music and adopted as the national anthem of the United States, which helped ensure that the all too oft-forgotten War of 1812 would retain some place in America’s collective memory. Continue reading

Earlier this week, the University of Maryland and their athletic uniform supplier, Under Armour, announced that the university’s football team “will wear football uniforms inspired by the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Baltimore and the writing of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ when it hosts West Virginia at Byrd Stadium” tomorrow, September 13.[1] The game will be played exactly 200 years to the day after Francis Scott Key penned “Defence of Fort McHenry,” a poem later set to music and adopted as the national anthem of the United States, which helped ensure that the all too oft-forgotten War of 1812 would retain some place in America’s collective memory. Continue reading

Category Archives: Commentary

Guest Post: American and Scottish Independence: Hearts and Minds

Simon Newman is Sir Denis Brogan Professor of American History at the University of Glasgow. His most recent book, A New World of Labor: The Development of Plantation Slavery in the British Atlantic, was published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2013. In this guest post, Newman draws parallels between the American campaign for independence in the 1770s, and the current campaign for Scottish independence.

On September 18th millions of voters in Scotland will head to the polls to answer a simple question: “Should Scotland be an independent country?” As an historian of the American Revolution living and working in Scotland I am struck by the parallels not just between the two movements for independence, but more significantly between the ways in which the British government in the eighteenth century and the UK government in the twenty-first century have challenged those who sought and seek independence. Continue reading

On September 18th millions of voters in Scotland will head to the polls to answer a simple question: “Should Scotland be an independent country?” As an historian of the American Revolution living and working in Scotland I am struck by the parallels not just between the two movements for independence, but more significantly between the ways in which the British government in the eighteenth century and the UK government in the twenty-first century have challenged those who sought and seek independence. Continue reading

The OId World of the New Republic

As someone who works on the late colonial period (1730s-1770s) in a field dominated by the “early republic,” it is easy to feel as though I am working on the margins of the field of early American history rather than what is actually the middle or center of what we usually define as early America (i.e., 1607 to somewhere between 1848 and 1861).[1] Yet, in this brief, speculative post, I will suggest that—in terms of my own subfield of political history and political culture—one of the things missing from much of the scholarship on the early republic is the colonial period itself. Continue reading

Guest Post: Teaching and the Problem with Parties in the Early Republic

Mark Boonshoft is a PhD candidate at Ohio State University. His work focuses on colleges and academies, especially the networks forged in them, and their role in the formation of revolutionary political culture.

As an undergraduate, I found the political history of the early republic to be fascinating. As a graduate student, I find teaching the subject to be utterly frustrating. This surprised me, though it shouldn’t have. I was already interested in early American history when I got to college. Most of my students don’t share that proclivity, to say the least.[1] Generally, they assume that the policy debates of the founding era and beyond—especially about banks, internal improvements, and federalism—are downright dry. That said, our students live in an era of rampant partisanship and government paralysis, punctuated by politicians’ ill-conceived attempts to claim the legacy of ‘the founders.’ The emergence of American party politics is pretty relevant to our students’ lives. So with many of us gearing up to get back into the classroom, I thought this would be a good time to start a discussion about teaching the history of early national party formation. Continue reading

As an undergraduate, I found the political history of the early republic to be fascinating. As a graduate student, I find teaching the subject to be utterly frustrating. This surprised me, though it shouldn’t have. I was already interested in early American history when I got to college. Most of my students don’t share that proclivity, to say the least.[1] Generally, they assume that the policy debates of the founding era and beyond—especially about banks, internal improvements, and federalism—are downright dry. That said, our students live in an era of rampant partisanship and government paralysis, punctuated by politicians’ ill-conceived attempts to claim the legacy of ‘the founders.’ The emergence of American party politics is pretty relevant to our students’ lives. So with many of us gearing up to get back into the classroom, I thought this would be a good time to start a discussion about teaching the history of early national party formation. Continue reading

Can The Comment

Like many academics, I’ve spent many hours this summer in conference rooms with fluorescent lighting and insufficient air conditioning. For the most part, this has been a real pleasure—after a year of teaching, it is always invigorating to hear others present their research and engage in fruitful conversations. But one part of the experience always fills me with dread: the comment. Continue reading

Like many academics, I’ve spent many hours this summer in conference rooms with fluorescent lighting and insufficient air conditioning. For the most part, this has been a real pleasure—after a year of teaching, it is always invigorating to hear others present their research and engage in fruitful conversations. But one part of the experience always fills me with dread: the comment. Continue reading

The Nation, the Global Game and the Weight of it All

For the past month, our eyes have been on the ball. Perfectly round, it flies and falls, across stadium skies through fields of grass, past fast, neon shoes and into goals, from Brazil to where we are. Our eyes follow. From Manaus and Fortaleza in the northern regions, traveling southward through Recife, Brasilia, Belo Horizonte, and Rio de Janeiro, near the Tropic of Capricorn, downwards to Porto Alegre. The World Cup has been a feast of the sensory and the dramatic, from the Amazon basin, where bugs abound with sweat, where sometimes torrential rain soaks shoes; and where, last night, near the busied streets of Rio and the ecstatic fun of the Copacabana, the sun set before the Christ the Redeemer Statue, and over the final game. For a month, we have seen the omnipresent national flags worn on people’s clothes and faces, and the victory runs, leaps, and hugs; as well as the tears that give you a sort of palpable agony, in the post-goal and final moments of every match. Continue reading

How Do You Pronounce This Blog’s Name, Anyway?

Back in 2012, when the initial ideas for this blog were first being thrown around, I suggested the name The Junto. I did so, not least because working at the Franklin Papers tends to keep Franklin on the brain. But I also suggested the name because the blog seemed to me to be analogous to the original group in that it was started by a bunch of upstarts with the intent of creating intellectual discourse amongst a supportive and engaged community. And those were the two most important initial goals of the blog. At the time, I never anticipated that there would ever be any confusion as to how to pronounce the name. That may have been a good thing since I probably would not have suggested it otherwise (“pronouncability” being pretty important when it comes to naming things, apparently). So, you might ask: “What is the correct pronunciation?” Well, that’s the thing. There doesn’t seem to be one, at least not nowadays. So, in a hopeful effort to settle the question, I decided to try to find out how people in the eighteenth century pronounced “Junto.” Continue reading

Back in 2012, when the initial ideas for this blog were first being thrown around, I suggested the name The Junto. I did so, not least because working at the Franklin Papers tends to keep Franklin on the brain. But I also suggested the name because the blog seemed to me to be analogous to the original group in that it was started by a bunch of upstarts with the intent of creating intellectual discourse amongst a supportive and engaged community. And those were the two most important initial goals of the blog. At the time, I never anticipated that there would ever be any confusion as to how to pronounce the name. That may have been a good thing since I probably would not have suggested it otherwise (“pronouncability” being pretty important when it comes to naming things, apparently). So, you might ask: “What is the correct pronunciation?” Well, that’s the thing. There doesn’t seem to be one, at least not nowadays. So, in a hopeful effort to settle the question, I decided to try to find out how people in the eighteenth century pronounced “Junto.” Continue reading

Benjamin Franklin and “our Seamen who were Prisoners in England”

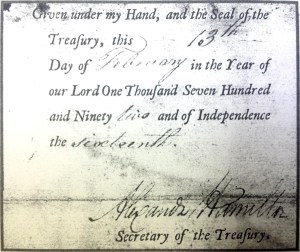

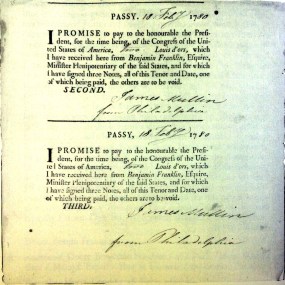

Earlier this week, I found myself sitting at my desk at the Franklin Papers faced with photostat copies of an “Alphabetical List of Escaped Prisoners” and a huge pile of promissory notes printed in triplicate by Franklin himself on the press he kept at his home in Passy, a suburb outside Paris. While I was going through them, I could not help but think back to the recent events surrounding the return of U.S. Army Sergeant, Bowe Bergdahl, the last remaining prisoner of the nation’s longest continuous period of war since the American Revolution. Politics aside, the Bergdahl affair speaks to the importance placed on coming to the aid of Americans detained in wartime. And what I had before me at my desk spoke to the same during the War for Independence. These men—largely privateersmen who had been captured on the high seas by the British and transported to English prisons—were among the very first Americans imprisoned on foreign soil during wartime and these documents reveal an often untold story about how the United States government and Benjamin Franklin dealt with this new problem.

Earlier this week, I found myself sitting at my desk at the Franklin Papers faced with photostat copies of an “Alphabetical List of Escaped Prisoners” and a huge pile of promissory notes printed in triplicate by Franklin himself on the press he kept at his home in Passy, a suburb outside Paris. While I was going through them, I could not help but think back to the recent events surrounding the return of U.S. Army Sergeant, Bowe Bergdahl, the last remaining prisoner of the nation’s longest continuous period of war since the American Revolution. Politics aside, the Bergdahl affair speaks to the importance placed on coming to the aid of Americans detained in wartime. And what I had before me at my desk spoke to the same during the War for Independence. These men—largely privateersmen who had been captured on the high seas by the British and transported to English prisons—were among the very first Americans imprisoned on foreign soil during wartime and these documents reveal an often untold story about how the United States government and Benjamin Franklin dealt with this new problem.

The Details Matter: On Ta-Nehisi Coates and Reparations

The attention Ta-Nehisi Coates’ essay on reparations has received is remarkable and welcome. But like most of the folks he’s directly appealing to—educated, mainstream liberals who read The Atlantic—I approached his essay skeptically, assuming reparations was an impractical, even irresponsible way to redress the crimes of slavery and the way its legacy, racism, continues to disadvantage all African Americans today. But by the end of it, I was convinced. A major reason why is because by reparations Coates, or at least the leading advocates for reparations he quotes in approval, aren’t arguing for simple payouts to African Americans. Coates knows too well that, lacking a more rigorous understanding of our nation’s history with slavery, and the continuing problems of institutionalized racism, cash payouts risk becoming little more than “hush-money.” Continue reading

The attention Ta-Nehisi Coates’ essay on reparations has received is remarkable and welcome. But like most of the folks he’s directly appealing to—educated, mainstream liberals who read The Atlantic—I approached his essay skeptically, assuming reparations was an impractical, even irresponsible way to redress the crimes of slavery and the way its legacy, racism, continues to disadvantage all African Americans today. But by the end of it, I was convinced. A major reason why is because by reparations Coates, or at least the leading advocates for reparations he quotes in approval, aren’t arguing for simple payouts to African Americans. Coates knows too well that, lacking a more rigorous understanding of our nation’s history with slavery, and the continuing problems of institutionalized racism, cash payouts risk becoming little more than “hush-money.” Continue reading

Putting “Republicanism” in Its Place

“By 1990,” wrote Daniel Rodgers, the concept of republicanism in American historiography “was everywhere and organizing everything, though perceptibly thinning out, like a nova entering its red giant phase.” A quarter of a century later, it can seem barely more than a dull glow—and in part, we have Rodgers’ essay to thank for dimming the lights. If republicanism’s 1970s high-water-mark was followed by a decade of furious debate over republicanism-versus-liberalism, scholarship after 1990 often framed itself as moving beyond precisely that anachronistic question. There was, apparently, no such conflict in the minds of revolutionary-era Americans. The problems that troubled them were different ones entirely.[1] Continue reading

“By 1990,” wrote Daniel Rodgers, the concept of republicanism in American historiography “was everywhere and organizing everything, though perceptibly thinning out, like a nova entering its red giant phase.” A quarter of a century later, it can seem barely more than a dull glow—and in part, we have Rodgers’ essay to thank for dimming the lights. If republicanism’s 1970s high-water-mark was followed by a decade of furious debate over republicanism-versus-liberalism, scholarship after 1990 often framed itself as moving beyond precisely that anachronistic question. There was, apparently, no such conflict in the minds of revolutionary-era Americans. The problems that troubled them were different ones entirely.[1] Continue reading