Joseph Yesurun Pinto, a 31 year-old Anglo-Dutch émigré in the autumn of 1760, had led New York’s Shearith Israel synagogue for barely a year when the second notice appeared in the papers. To re-commemorate the British conquest of Canada, all “Christian societies” and “houses of worship” would celebrate a day of thanksgiving on Thursday, October 23d. Over the past decade, New Englanders and their neighbors had held at least 50 fast days, many to lament God’s judgments against America, or to reform their wayward behavior. The proclamation of a thanksgiving day likely brought some measure of relief and joy.

Joseph Yesurun Pinto, a 31 year-old Anglo-Dutch émigré in the autumn of 1760, had led New York’s Shearith Israel synagogue for barely a year when the second notice appeared in the papers. To re-commemorate the British conquest of Canada, all “Christian societies” and “houses of worship” would celebrate a day of thanksgiving on Thursday, October 23d. Over the past decade, New Englanders and their neighbors had held at least 50 fast days, many to lament God’s judgments against America, or to reform their wayward behavior. The proclamation of a thanksgiving day likely brought some measure of relief and joy.

Tag Archives: Early Republic

The JuntoCast, Episode 13: Education in Early America

We’re happy to bring you the thirteenth episode of “The JuntoCast.” Continue reading

We’re happy to bring you the thirteenth episode of “The JuntoCast.” Continue reading

Decoding Diplomacy

Ciphers, codes, and keys—plus reflections on how to encrypt sensitive developments in early American diplomacy—run through the papers of two generations in the Adams family’s saga of public service. So how did they use secrecy in statecraft? Continue reading

The Week in Early American History

Welcome to your weekly roundup of early American headline news. To the links! Continue reading

Welcome to your weekly roundup of early American headline news. To the links! Continue reading

Making the Adams Papers

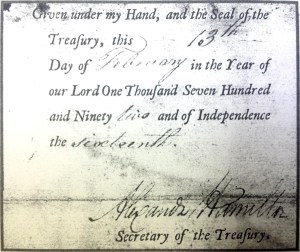

Nearly a quarter of a million manuscript pages, and almost fifty volumes to show for it: As we mark the 60th anniversary of production at the Adams Papers editorial project, here’s an inside look at our process, from manuscript to volume. Continue reading

Nearly a quarter of a million manuscript pages, and almost fifty volumes to show for it: As we mark the 60th anniversary of production at the Adams Papers editorial project, here’s an inside look at our process, from manuscript to volume. Continue reading

Culture Club

Here’s your seasonal roundup of early American art on exhibit. Add your finds below!

Here’s your seasonal roundup of early American art on exhibit. Add your finds below!

Continue reading

The OId World of the New Republic

As someone who works on the late colonial period (1730s-1770s) in a field dominated by the “early republic,” it is easy to feel as though I am working on the margins of the field of early American history rather than what is actually the middle or center of what we usually define as early America (i.e., 1607 to somewhere between 1848 and 1861).[1] Yet, in this brief, speculative post, I will suggest that—in terms of my own subfield of political history and political culture—one of the things missing from much of the scholarship on the early republic is the colonial period itself. Continue reading

Autumn Reads

Here’s our fall preview of new titles—share your finds in the comments! Continue reading

Here’s our fall preview of new titles—share your finds in the comments! Continue reading

Guest Post: Teaching and the Problem with Parties in the Early Republic

Mark Boonshoft is a PhD candidate at Ohio State University. His work focuses on colleges and academies, especially the networks forged in them, and their role in the formation of revolutionary political culture.

As an undergraduate, I found the political history of the early republic to be fascinating. As a graduate student, I find teaching the subject to be utterly frustrating. This surprised me, though it shouldn’t have. I was already interested in early American history when I got to college. Most of my students don’t share that proclivity, to say the least.[1] Generally, they assume that the policy debates of the founding era and beyond—especially about banks, internal improvements, and federalism—are downright dry. That said, our students live in an era of rampant partisanship and government paralysis, punctuated by politicians’ ill-conceived attempts to claim the legacy of ‘the founders.’ The emergence of American party politics is pretty relevant to our students’ lives. So with many of us gearing up to get back into the classroom, I thought this would be a good time to start a discussion about teaching the history of early national party formation. Continue reading

As an undergraduate, I found the political history of the early republic to be fascinating. As a graduate student, I find teaching the subject to be utterly frustrating. This surprised me, though it shouldn’t have. I was already interested in early American history when I got to college. Most of my students don’t share that proclivity, to say the least.[1] Generally, they assume that the policy debates of the founding era and beyond—especially about banks, internal improvements, and federalism—are downright dry. That said, our students live in an era of rampant partisanship and government paralysis, punctuated by politicians’ ill-conceived attempts to claim the legacy of ‘the founders.’ The emergence of American party politics is pretty relevant to our students’ lives. So with many of us gearing up to get back into the classroom, I thought this would be a good time to start a discussion about teaching the history of early national party formation. Continue reading

Guest Post: The Decline of Barbers? Or, the Risks and Rewards of Quantitative Analysis

Today’s guest post is authored by Sean Trainor, a historian of the early American republic with an interest in the intersection of labor, popular culture, and the body. He is a PhD candidate in History and Women’s Studies and Pennsylvania State University, where his dissertation examines the history of men’s grooming in the urban United States between the turn of the nineteenth century and the American Civil War.

A few weeks ago, I finished compiling a database, long in the works, containing the names and addresses of all of the barbers in the cities of Boston, Cincinnati, and New Orleans between 1800 and 1860. Thrilling, I know, but the project has broader implications for historians interested in the intersection of quantitative and cultural history which, if you’ll bear with a brief exposition, I’ll discuss below.

A few weeks ago, I finished compiling a database, long in the works, containing the names and addresses of all of the barbers in the cities of Boston, Cincinnati, and New Orleans between 1800 and 1860. Thrilling, I know, but the project has broader implications for historians interested in the intersection of quantitative and cultural history which, if you’ll bear with a brief exposition, I’ll discuss below.