A Call to the Most Bland and Boring Pieces of Paper You’ve Ever Skipped Over in the Archives

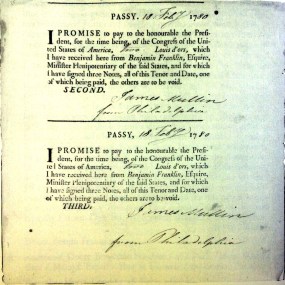

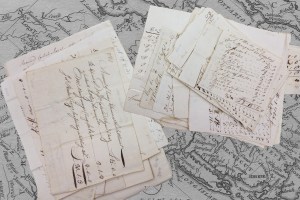

Vouchers! Receipts! Bills of exchange!

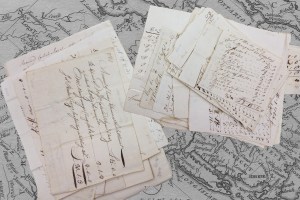

The paperwork of empire, particularly that of credit and finance, is probably not what gets most of us up in the morning. In the archives, we skip over the dull sections of the finding aids—warrants, no thanks!—and instead dive into correspondence and maps and bound volumes and clippings. The more adventurous of us might even call up account books—but those individual receipts? They’re lucky if we ever take them out of the box.

And why would we? Unless we live in a world of down-and-dirty finance or economics or material culture, they seem not only besides the point, but, even more, incredibly hollow. What do we get from reading a quick statement that someone was eventually paid for delivering a barrel of pickled cabbage in 1760? Especially when we can read in frantic detail the correspondence about how that barrel fell into the Mohawk River, burst open, got hauled back onto a bateau, arrived at Fort Stanwix, was re-opened, reeked, was declared unfit for consumption, continued to reek, was declared fit for consumption, reeked some more, ordered northward to Oswego, reeked still, and finally was delivered to a garrison comprised mostly of Germans who (our correspondents assumed) would think they’d been gifted sauerkraut.[1]

It’s the correspondence, we might argue, that gives us actors and action. In it, even a barrel—brown, wooden, boring—becomes something dynamic.

But who delivered that barrel? How long did it take him? Where did he begin his trip? Was he a merchant contractor, a militia man, a professional sled driver? And what did he get out of a journey, in the dead of winter, through the type of paralyzing cold you can only feel in upstate New York, with barrels of spoiled pickled cabbage?

Exceedingly important questions like these suddenly make the boring, bland, bureaucratic paperwork appear just a little (a very little?) more interesting. Continue reading →

We begin this Week in Early American History with James Oakes’ powerful and timely reflection on white abolitionism. “

We begin this Week in Early American History with James Oakes’ powerful and timely reflection on white abolitionism. “