When I consider the non-early-American history books that have had the greatest impact on the way I think, two stand out in particular. One is Ross McKibbin’s The Evolution of the Labour Party, 1910-1924; the other, CLR James’s Beyond A Boundary. The former is the most obviously “academic” of the two; the opportunity to write a Junto post primarily concerned with cricket, however, means that today I’ll focus on the latter.[1]

When I consider the non-early-American history books that have had the greatest impact on the way I think, two stand out in particular. One is Ross McKibbin’s The Evolution of the Labour Party, 1910-1924; the other, CLR James’s Beyond A Boundary. The former is the most obviously “academic” of the two; the opportunity to write a Junto post primarily concerned with cricket, however, means that today I’ll focus on the latter.[1]

Both books influenced me for their creativity in approaching politics and society. McKibbin’s insight that “political action is the result of social and cultural attitudes which are not primarily political” has remained with me ever since; a useful reminder that in writing political history, we have to try and find ways of recovering political mindsets not only by looking at what political actors say, but also the many and varied ways they actually do things. James, too, calls for an approach to studying the past that looks beyond a narrow scope of inquiry, in his famous question ‘What do they know of cricket, who only cricket know?’ Continue reading

This week’s roundtable

This week’s roundtable

Shortly after the publication of

Shortly after the publication of

We talk a lot about accessibility in historical writing. Many of us worry whether the academic historical profession has much to say to a broad popular audience.

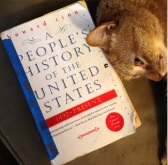

We talk a lot about accessibility in historical writing. Many of us worry whether the academic historical profession has much to say to a broad popular audience.  Earlier this month I finished teaching my first public history course. I’ve long been concerned about how professional historians, especially academic historians, (often don’t) communicate with the public and, in turn, the general public’s misunderstanding of the historian’s craft. Teaching a public history course made these apprehensions central to my work in the classroom. My students and I grappled with a different kind of historiography, a less formal historiography consisting of public opinion, incomplete recollections of elementary and secondary history education, and a “master narrative” that usually dominates stories of the American past told by many public figures, a narrative steeped in patriotism, heritage, and commemoration. More than ever, I found myself challenging my students (in all my classes, not just the public history course) to take a three-part approach in their studies: learn about the past, learn about how professional historians have interpreted the past, and learn about how the general public understands the past. This became yet another way to demonstrate that course content has relevance outside the classroom and beyond the semester.

Earlier this month I finished teaching my first public history course. I’ve long been concerned about how professional historians, especially academic historians, (often don’t) communicate with the public and, in turn, the general public’s misunderstanding of the historian’s craft. Teaching a public history course made these apprehensions central to my work in the classroom. My students and I grappled with a different kind of historiography, a less formal historiography consisting of public opinion, incomplete recollections of elementary and secondary history education, and a “master narrative” that usually dominates stories of the American past told by many public figures, a narrative steeped in patriotism, heritage, and commemoration. More than ever, I found myself challenging my students (in all my classes, not just the public history course) to take a three-part approach in their studies: learn about the past, learn about how professional historians have interpreted the past, and learn about how the general public understands the past. This became yet another way to demonstrate that course content has relevance outside the classroom and beyond the semester.