In just over a week from now, the Massachusetts Historical Society is hosting, “‘So Sudden an Alteration’: The Causes, Course, and Consequences of the American Revolution,” an important conference on the American Revolution in recognition of the the 250th anniversary of the Stamp Act. This is the second of three conferences dedicated to rediscovering or re-energizing study of the American Revolution, the first of which, “The American Revolution Reborn,” was hosted by the McNeil Center for Early American Studies in the spring of 2013. And so with the conference fast approaching, I want to use this piece to think about the specific moment and circumstances in which American Revolution studies currently finds itself, which has been the catalyst for this series of conferences, and suggest possibilities going forward. The primary circumstance of that moment, with which many seem to agree, is that the study of the Revolution is in a rut, plodding along in the same “well-worn grooves of historical inquiry” for the “past fifty years,” according to the conference’s call for papers. Continue reading

In just over a week from now, the Massachusetts Historical Society is hosting, “‘So Sudden an Alteration’: The Causes, Course, and Consequences of the American Revolution,” an important conference on the American Revolution in recognition of the the 250th anniversary of the Stamp Act. This is the second of three conferences dedicated to rediscovering or re-energizing study of the American Revolution, the first of which, “The American Revolution Reborn,” was hosted by the McNeil Center for Early American Studies in the spring of 2013. And so with the conference fast approaching, I want to use this piece to think about the specific moment and circumstances in which American Revolution studies currently finds itself, which has been the catalyst for this series of conferences, and suggest possibilities going forward. The primary circumstance of that moment, with which many seem to agree, is that the study of the Revolution is in a rut, plodding along in the same “well-worn grooves of historical inquiry” for the “past fifty years,” according to the conference’s call for papers. Continue reading

Category Archives: Historiography

Guest Post: William Black, Gordon Wood’s Notecards and the Two Presentisms

Today we are pleased to have a guest post from William R. Black (@w_r_black), a PhD student of history at Rice University. His research examines how Cumberland Presbyterians dealt with slavery, sectionalism, theological controversy, and professionalization in the nineteenth century.

Gordon Wood riled up the #twitterstorians with a review of his advisor Bernard Bailyn’s latest book, Sometimes an Art: Nine Essays on History. Much of the review is not so much about Bailyn as it is about later generations of historians, who (according to Wood) have abandoned narrative history for “fragmentary,” obscure monographs on subaltern peoples. Wood attacks these historians for being “anachronistic—condemning the past for not being more like the present.” He continues: Continue reading

Gordon Wood riled up the #twitterstorians with a review of his advisor Bernard Bailyn’s latest book, Sometimes an Art: Nine Essays on History. Much of the review is not so much about Bailyn as it is about later generations of historians, who (according to Wood) have abandoned narrative history for “fragmentary,” obscure monographs on subaltern peoples. Wood attacks these historians for being “anachronistic—condemning the past for not being more like the present.” He continues: Continue reading

The Problem of Southern Indians’ Allegiance in the American Revolution

So you know what’s hilarious? Trying to revise your dissertation into a book during the semester. I will admit that I am in the middle of editing my worst dissertation chapter, and am yelling out of a metaphorical pit of despair that’s been dug by a combination of bad prose and end-of-the-semester angst. Part of these struggles have to do with the fact that even after writing the chapter, submitting it, and defending it, I’m still not really sure what this chapter’s argument needs to say. This problem is directly tied to the fact that I found (and continue to find) myself befuddled by late-eighteenth-century Southern Indian affairs. So many factions! So much switching of sides! So many different ways I manage to mis-type Scots-Creek go-between Alexander McGillivray’s last name![1] Continue reading

Economic Growth and the Historicity of Capitalism

One of the central characteristics of the new history of capitalism has been its tendency to defer the question of just what “capitalism” is. The project’s enquiry starts with the question, not with a predetermined answer. But in order to know where to look, historians have to start with some idea about what makes a place and a time capitalist. As Tim Shenk points out in a recent article in The New Republic, the clue around which they converge is economic growth. Continue reading

One of the central characteristics of the new history of capitalism has been its tendency to defer the question of just what “capitalism” is. The project’s enquiry starts with the question, not with a predetermined answer. But in order to know where to look, historians have to start with some idea about what makes a place and a time capitalist. As Tim Shenk points out in a recent article in The New Republic, the clue around which they converge is economic growth. Continue reading

Telling the Story of Women in Printing

Today is Ada Lovelace Day, an international celebration of women in STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) both past and present named after the early nineteenth-century British mathematician. Here in our corner of early American studies, I want to mark the occasion by working through a question that I’ve worked on in my own writing for years: how do we effectively integrate women into the history of printing in early America?

Today is Ada Lovelace Day, an international celebration of women in STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) both past and present named after the early nineteenth-century British mathematician. Here in our corner of early American studies, I want to mark the occasion by working through a question that I’ve worked on in my own writing for years: how do we effectively integrate women into the history of printing in early America?

Is the History of Capitalism the History of Everything?

Seth Rockman begins and ends his recent essay on the “new history of capitalism” by describing capitalism as an economic system; but one of the features of the movement he describes is that it rightly treats capitalism as much more than that. As Rockman admits, “it is difficult to say what exactly it excludes.”[1] What’s most provocative and powerful about the new history of capitalism is precisely the fact that it recognizes and tries to historicize the pervasiveness of capitalism as a system that touches every aspect of our lives—everyone’s lives. Capitalism isn’t just in the workplace and the marketplace; as Jeffrey Sklansky has suggested, it’s in our very ways of being, seeing, and believing. But if the history of capitalism is an empire with no borders, just what kind of claims can it be making?[2] Continue reading

Seth Rockman begins and ends his recent essay on the “new history of capitalism” by describing capitalism as an economic system; but one of the features of the movement he describes is that it rightly treats capitalism as much more than that. As Rockman admits, “it is difficult to say what exactly it excludes.”[1] What’s most provocative and powerful about the new history of capitalism is precisely the fact that it recognizes and tries to historicize the pervasiveness of capitalism as a system that touches every aspect of our lives—everyone’s lives. Capitalism isn’t just in the workplace and the marketplace; as Jeffrey Sklansky has suggested, it’s in our very ways of being, seeing, and believing. But if the history of capitalism is an empire with no borders, just what kind of claims can it be making?[2] Continue reading

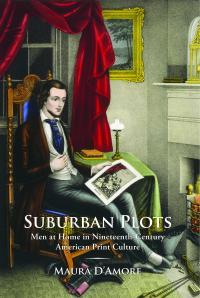

Review: Maura D’Amore, Suburban Plots: Men at Home in Nineteenth-Century American Print Culture

Maura D’Amore, Suburban Plots: Men at Home in Nineteenth-Century American Print Culture. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014.

The world was a strange and startling place for Rip Van Winkle when he awoke from a twenty-year nap in New York’s Catskill Mountains. He had ventured to the woods to find a moment’s peace from “the labour of the farm and the clamour of his wife.”[1] Now well rested, bountifully bearded, and slightly disoriented, Van Winkle returned to his village anxious to understand the changes that left him “alone in the world,” but pleased that he was now part of a “more fraternal, organic domestic order.”[2] In the time since his fateful game of ninepins mixed with moonshine, Van Winkle, along with his male village compatriots, was now free to exercise his own masculine alternatives to traditionally female forms of domesticity. Maura D’Amore opens her book Suburban Plots: Men at Home in Nineteenth-Century American Print Culture with this unconventional reading of Washington Irving’s well-known tale. Seeking to understand the emergence of what she terms “male domesticity” in the nineteenth century—defined (somewhat inconsistently) as an ideology of “self-nurture in suburban environments [that provided] an antidote to the malaise of urban life and the strictures of feminine self-sacrifice”—D’Amore presents Rip Van Winkle as a prototype of various middle- and upper-class men who attempted to implement domesticity “on [their] own terms” in the midst of a quickly industrializing and alien world.[3] Continue reading

The world was a strange and startling place for Rip Van Winkle when he awoke from a twenty-year nap in New York’s Catskill Mountains. He had ventured to the woods to find a moment’s peace from “the labour of the farm and the clamour of his wife.”[1] Now well rested, bountifully bearded, and slightly disoriented, Van Winkle returned to his village anxious to understand the changes that left him “alone in the world,” but pleased that he was now part of a “more fraternal, organic domestic order.”[2] In the time since his fateful game of ninepins mixed with moonshine, Van Winkle, along with his male village compatriots, was now free to exercise his own masculine alternatives to traditionally female forms of domesticity. Maura D’Amore opens her book Suburban Plots: Men at Home in Nineteenth-Century American Print Culture with this unconventional reading of Washington Irving’s well-known tale. Seeking to understand the emergence of what she terms “male domesticity” in the nineteenth century—defined (somewhat inconsistently) as an ideology of “self-nurture in suburban environments [that provided] an antidote to the malaise of urban life and the strictures of feminine self-sacrifice”—D’Amore presents Rip Van Winkle as a prototype of various middle- and upper-class men who attempted to implement domesticity “on [their] own terms” in the midst of a quickly industrializing and alien world.[3] Continue reading

The OId World of the New Republic

As someone who works on the late colonial period (1730s-1770s) in a field dominated by the “early republic,” it is easy to feel as though I am working on the margins of the field of early American history rather than what is actually the middle or center of what we usually define as early America (i.e., 1607 to somewhere between 1848 and 1861).[1] Yet, in this brief, speculative post, I will suggest that—in terms of my own subfield of political history and political culture—one of the things missing from much of the scholarship on the early republic is the colonial period itself. Continue reading

On Gender and Genre

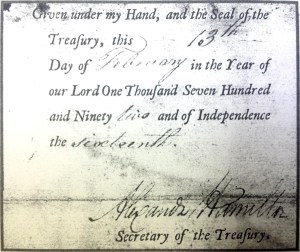

Do biographies of women have different conventions to biographies of men? Setting out on a new historical project—which, at least for the moment, takes the form of a biography of Angelica Schuyler Church (not pictured! That’s Dolley Madison)—I’ve been thinking a lot about the particular confluence of what often seem to be maligned and marginalised fields even in their own right: women’s history and biography. I have a lot still to learn about both. But let me offer some preliminary considerations here, and invite Junto readers to pitch in in the comments.

Do biographies of women have different conventions to biographies of men? Setting out on a new historical project—which, at least for the moment, takes the form of a biography of Angelica Schuyler Church (not pictured! That’s Dolley Madison)—I’ve been thinking a lot about the particular confluence of what often seem to be maligned and marginalised fields even in their own right: women’s history and biography. I have a lot still to learn about both. But let me offer some preliminary considerations here, and invite Junto readers to pitch in in the comments.

Putting “Republicanism” in Its Place

“By 1990,” wrote Daniel Rodgers, the concept of republicanism in American historiography “was everywhere and organizing everything, though perceptibly thinning out, like a nova entering its red giant phase.” A quarter of a century later, it can seem barely more than a dull glow—and in part, we have Rodgers’ essay to thank for dimming the lights. If republicanism’s 1970s high-water-mark was followed by a decade of furious debate over republicanism-versus-liberalism, scholarship after 1990 often framed itself as moving beyond precisely that anachronistic question. There was, apparently, no such conflict in the minds of revolutionary-era Americans. The problems that troubled them were different ones entirely.[1] Continue reading

“By 1990,” wrote Daniel Rodgers, the concept of republicanism in American historiography “was everywhere and organizing everything, though perceptibly thinning out, like a nova entering its red giant phase.” A quarter of a century later, it can seem barely more than a dull glow—and in part, we have Rodgers’ essay to thank for dimming the lights. If republicanism’s 1970s high-water-mark was followed by a decade of furious debate over republicanism-versus-liberalism, scholarship after 1990 often framed itself as moving beyond precisely that anachronistic question. There was, apparently, no such conflict in the minds of revolutionary-era Americans. The problems that troubled them were different ones entirely.[1] Continue reading