Robert Whitaker is a doctoral candidate in History at the University of Texas at Austin. His dissertation, “Policing Globalization: The Imperial Origins of International Police Cooperation, 1918-1960” studies the relationship between the British Empire and international police organizations, such as Interpol. He serves as an Assistant General Editor for the journal Britain and the World, and is the creator of the YouTube series History Respawned. Bryan S. Glass teaches the history of Britain’s interactions with the World at Texas State University. He is the founding member and General Editor of The British Scholar Society and serves as an Editor of the Britain and the World book series (Palgrave Macmillan). His publications include an article in the Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, The Scottish Nation at Empire’s End (Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming), and a co-edited volume with John MacKenzie entitled Scotland, Empire and Decolonisation in the Twentieth Century (Manchester University Press, forthcoming).

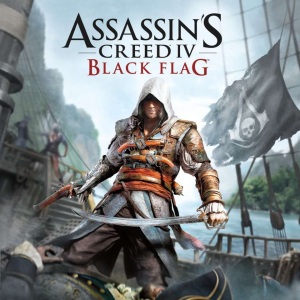

French game company Ubisoft has turned early American history into an age of booty. Over the past two years, the company has used early American history as the backdrop for three successive and successful titles in their Assassin’s Creed franchise: Assassin’s Creed III, Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation, and Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag. The most recent of these titles, Black Flag, is set in the Golden Age of Piracy during the early eighteenth century, and is easily the most profitable and well received of the three. Critics and players have praised Black Flag for its gameplay, graphics, and music—or rather, sea shanties.[1] But the biggest reason why this game has garnered accolades and high sales is because of its use, or misuse, of history. More than any other Assassin’s Creed game, Black Flag plays fast and loose with the historical record. It skews away from accuracy in favor of fun at almost every turn. Yet even as Black Flag thumbs its nose at the concerns of academic history, it nevertheless succeeds, perhaps better than any previous title in the series, in giving players a sensibility of the age. Continue reading

I’ve just begun the arduous task of transforming my recently completed dissertation about colonial and revolutionary Georgia into a work worthy of an academic press. Part of this process, for me at least, has been to re-examine my notecards (actually an enormous Excel spreadsheet), seeking new gems, ideas, and angles. In so doing, I’ve rediscovered a tidbit that I want to further develop during the manuscript process and I humbly submit this post as a solicitation to the blog’s readers, seeking their varied and expert insights.

I’ve just begun the arduous task of transforming my recently completed dissertation about colonial and revolutionary Georgia into a work worthy of an academic press. Part of this process, for me at least, has been to re-examine my notecards (actually an enormous Excel spreadsheet), seeking new gems, ideas, and angles. In so doing, I’ve rediscovered a tidbit that I want to further develop during the manuscript process and I humbly submit this post as a solicitation to the blog’s readers, seeking their varied and expert insights.

Like many of you, I find myself teaching the first half of the U.S. history survey this fall. The first few times through the course, I used a textbook and appreciated the clear organizational structure and built-in pacing. Teaching with a textbook felt like teaching with training wheels, and I certainly needed them for my first few laps. But as my confidence grew, so did my desire to assign primary sources, articles, monographs, museum catalogs, and other readings. While I am impressed with the quality of many texts – Eric Foner’s Give Me Liberty, and Kevin Schultz’s HIST are among my favorites – I cannot justify assigning an (often outrageously) expensive textbook if it is not going to be the cornerstone of my course. But my course evaluations often include requests for textbooks, particularly among athletes or other students with serial absences. I have tried placing a textbook on reserve, but in the three semesters of doing so, no one has ever checked out the book. It seems like our discipline could use an affordable, synthetic safety net for students who would like one.

Like many of you, I find myself teaching the first half of the U.S. history survey this fall. The first few times through the course, I used a textbook and appreciated the clear organizational structure and built-in pacing. Teaching with a textbook felt like teaching with training wheels, and I certainly needed them for my first few laps. But as my confidence grew, so did my desire to assign primary sources, articles, monographs, museum catalogs, and other readings. While I am impressed with the quality of many texts – Eric Foner’s Give Me Liberty, and Kevin Schultz’s HIST are among my favorites – I cannot justify assigning an (often outrageously) expensive textbook if it is not going to be the cornerstone of my course. But my course evaluations often include requests for textbooks, particularly among athletes or other students with serial absences. I have tried placing a textbook on reserve, but in the three semesters of doing so, no one has ever checked out the book. It seems like our discipline could use an affordable, synthetic safety net for students who would like one.

Sept. 19-21, 2013 marked the

Sept. 19-21, 2013 marked the