John Adams thought that James Otis set the whole American Revolution in motion in 1761. Otis’ argument against writs of assistance, in a legal case that year, Adams wrote, “was the first scene of the first Act of opposition to the Arbitrary claims of Great Britain. Then and there the Child Independence was born.”[1] Of course, Adams also though that July 2nd would be the most famous date in history. So forgive me for at least questioning Adams’ view that the “Writs of Assistance Case” basically jumpstarted the Revolution. That said, I do think the evidence base for the “Writs of Assistance Case” suggests that it was a major turning point in the development of the colonial legal profession. Picking up on themes in yesterday’s guest post by Craig Hanlon, the case may help make sense of the connections between legal professionalization and the American Revolution. Continue reading

John Adams thought that James Otis set the whole American Revolution in motion in 1761. Otis’ argument against writs of assistance, in a legal case that year, Adams wrote, “was the first scene of the first Act of opposition to the Arbitrary claims of Great Britain. Then and there the Child Independence was born.”[1] Of course, Adams also though that July 2nd would be the most famous date in history. So forgive me for at least questioning Adams’ view that the “Writs of Assistance Case” basically jumpstarted the Revolution. That said, I do think the evidence base for the “Writs of Assistance Case” suggests that it was a major turning point in the development of the colonial legal profession. Picking up on themes in yesterday’s guest post by Craig Hanlon, the case may help make sense of the connections between legal professionalization and the American Revolution. Continue reading

Category Archives: Research

Guest Post: A Series of Fortunate Events: Navigating the Eighteenth-Century World with George Galphin

Today’s guest post comes from Bryan Rindfleisch, Assistant Professor of History at Marquette University. Bryan received his Ph.D. from the University of Oklahoma, in 2014, where he specialized in early American, Native American, and Atlantic world history. His book manuscript focuses on the intersections of colonial, Native, imperial, and Atlantic histories, peoples, and places in eighteenth-century North America.

It’s inevitable. At some point, a friendly conversation about my research—with family and friends, colleagues, students, or even a random stranger at the local coffee shop—will take an unfortunate turn. All it takes is that one question: “Who is George Galphin?” Continue reading

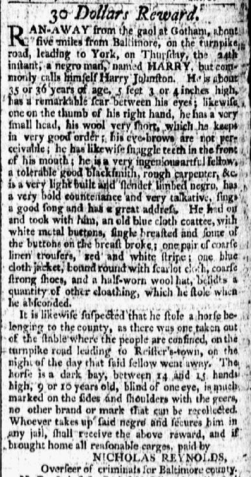

Guest Post: The Art of Absconding: Slave Fugitivity in the Early Republic

Guest Poster Shaun Wallace (@Shaun_Wallace_) is an Economic and Social Research Council-funded Ph.D. candidate at the University of Stirling. His dissertation examines how reading and writing influenced and aided slave decision-making in the early republic. Shaun holds a B.A. (Hons.) and a MRes. from the University of Stirling and is president of Historical Perspectives, a Glasgow-based historical society run by and for graduate students in the United Kingdom.

A “very ingenious artful fellow” appears a peculiar description of a runaway advertised for recapture. The advertisement, for Harry or Harry Johnstone, featured in Baltimore’s Federal Gazette newspaper, on May 2, 1800, at the request of Nicholas Reynolds, overseer of criminals for Baltimore County. Harry had absconded from Gotham gaol, near Baltimore. Reynolds described Harry as a “tolerable good blacksmith” and a “rough carpenter.” A “very talkative” slave, he was a man of “great address.” On first impression a relatively congenial description; in actuality, Reynolds’s use of the term “artful” condemned the runaway.[1]

A “very ingenious artful fellow” appears a peculiar description of a runaway advertised for recapture. The advertisement, for Harry or Harry Johnstone, featured in Baltimore’s Federal Gazette newspaper, on May 2, 1800, at the request of Nicholas Reynolds, overseer of criminals for Baltimore County. Harry had absconded from Gotham gaol, near Baltimore. Reynolds described Harry as a “tolerable good blacksmith” and a “rough carpenter.” A “very talkative” slave, he was a man of “great address.” On first impression a relatively congenial description; in actuality, Reynolds’s use of the term “artful” condemned the runaway.[1]

Continue reading

Before the Trail

Pratt must be paid. There was a route to examine one last time, and three shirts to stuff into a knapsack bulging with flannels and history books, powder and shot. The Berkshire Hills trip was a rush job; he needed to return for graduation in late August, 1844. Into the knapsack went a 4” x 2½” dusky-green journal, with shorthand notes in pencil. After a boyhood spent hunting and riding bareback on the Medford frontier, the blue-eyed Harvard senior, 20, knew how to pack for a research errand into the wilderness. Already, he boasted colorful adventures from past summer forays, fine-tuning the field skills that history professor Jared Sparks did not cover in class. Take July 1841: Scaling his first New Hampshire ravine, the rookie historian slipped and swung free, clawing air. As he “shuddered” and clung to the crag, a hard sheaf of pebbles fell, “clattering hundreds of feet” to the sunny gulf below.

Personal Networks and a First Draft of the Literary Canon

Antebellum editors were bulk retailers. Whatever else their business involved, it happened at scale, and I’m often astonished by how much prose a nineteenth-century newspaper or magazine editor could churn out in a day. Of course, most of that prose was recycled, and much of it was banal. As a forthcoming article by Ryan Cordell, based on research by the Viral Texts Project at Northeastern University, observes, the most-reprinted antebellum newspaper articles were pieces of “information literature”—not news, but scrapbookable things like an 1853 starch recipe or a clipping about the dietary value of tomatoes.[1] Apparently, antebellum readers welcomed such textual flotsam—but it was especially useful to editors, who needed a steady flood of context-free, easily resized gobbets of writing for their pages.

Antebellum editors were bulk retailers. Whatever else their business involved, it happened at scale, and I’m often astonished by how much prose a nineteenth-century newspaper or magazine editor could churn out in a day. Of course, most of that prose was recycled, and much of it was banal. As a forthcoming article by Ryan Cordell, based on research by the Viral Texts Project at Northeastern University, observes, the most-reprinted antebellum newspaper articles were pieces of “information literature”—not news, but scrapbookable things like an 1853 starch recipe or a clipping about the dietary value of tomatoes.[1] Apparently, antebellum readers welcomed such textual flotsam—but it was especially useful to editors, who needed a steady flood of context-free, easily resized gobbets of writing for their pages.

The bulk-retail principle applied to literary editors, too, and the difference between “literary” and other kinds of antebellum periodical work is hard to define. For the last couple of weeks, I’ve been thinking about what that meant for the formation of an American literary canon in the antebellum period.

Making the Most of Your Time in the Archives: Research Technology

As funding budgets shrink, many historians face increased pressure to make the most of their time in distant archives. For a number of years now, a lot of researchers have favored a good digital camera, which (theoretically) allows for a faster gathering of primary source materials than traditional note-taking methods. Of course, as historian Larry Cebula humorously observed, failure to exercise good digital stewardship with your own personal archives can have disastrous consequences.

As funding budgets shrink, many historians face increased pressure to make the most of their time in distant archives. For a number of years now, a lot of researchers have favored a good digital camera, which (theoretically) allows for a faster gathering of primary source materials than traditional note-taking methods. Of course, as historian Larry Cebula humorously observed, failure to exercise good digital stewardship with your own personal archives can have disastrous consequences.

The Importance of Partisanship in New York City, ca. 1769–1775

On April 25, 1775, hundreds of New Yorkers acknowledged receiving “a Good firelock, Bayonet, Cartouch Box, and Belt.” Six days after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and three days after Israel (Isaac) Bissell told New Yorkers the news, Alexander McDougall mobilized support against the British. The War of American Independence had reached New York and, with hundreds of supporters, McDougall was ready to fight.[1] By April 1775, McDougall was a revered figure across colonial America, widely known as “the Wilkes of New York.” He was an individual who, like John Wilkes, was perceived as willing to fight for the liberties of the press, the people’s welfare, and against arbitrary rule.[2] McDougall’s popularity, by 1775, had been five years in the making. But, in 2015, historians are yet to fully appreciate the role he played in the coming of the Revolution. In this post, I want to reemphasize his influence in affecting New Yorkers’ allegiances. Continue reading

On April 25, 1775, hundreds of New Yorkers acknowledged receiving “a Good firelock, Bayonet, Cartouch Box, and Belt.” Six days after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and three days after Israel (Isaac) Bissell told New Yorkers the news, Alexander McDougall mobilized support against the British. The War of American Independence had reached New York and, with hundreds of supporters, McDougall was ready to fight.[1] By April 1775, McDougall was a revered figure across colonial America, widely known as “the Wilkes of New York.” He was an individual who, like John Wilkes, was perceived as willing to fight for the liberties of the press, the people’s welfare, and against arbitrary rule.[2] McDougall’s popularity, by 1775, had been five years in the making. But, in 2015, historians are yet to fully appreciate the role he played in the coming of the Revolution. In this post, I want to reemphasize his influence in affecting New Yorkers’ allegiances. Continue reading

Historical Charts and David Ramsay’s Narrative of Progress

A while back Slate’s “The Vault” blog ran a piece on John Sparks’s “Histomap” from 1931. I was recently reminded of that post as I came across a number of eighteenth-century historical charts during my dissertation research on eighteenth-century American history culture.[1] In the eighteenth century, there were conflicting understandings of historical time. Some understood time to be cyclical, as evidenced by the rise and (inevitable) fall of empires throughout history. Increasingly, however, historical time was coming to be understood as linear (in a mechanical, Newtonian sense). With the linear conception came the idea of historical time as being fundamentally progressive. This conception was further distinguished by those who understood it in terms of a narrative of social and political progress and those who understood it in millennialist terms, i.e., time progressing toward the end-of-days. These ideas shaped the ways in which one thought about history, and, in a time when historical distance was far more truncated than today, they had a profound effect on how one viewed their contemporary world. Historical understanding and, hence, historical writing were undergoing significant shifts in the eighteenth century. One of the by-products of these developments was the historical chart.

The King’s Arms?

Paper soldiers on the march, and tin men tilting at swordpoint: these were the first battle ranks that Grenville Howland Norcross, aged 11 in Civil War Boston, led to glory. Between phantom invasions and replays of Antietam with “relics” received as gifts, Norcross gobbled up the military heroics popularized by the era’s dime novels. In a childhood diary that illustrates how “lowbrow” literature grabbed the imagination of a warsick homefront, Norcross chronicled his progress through the antics of Kate Sharp, Old Hal Williams, and Crazy Dan. By 1875, Norcross had outgrown his toy battalions, graduated Harvard, and stepped into a law career. An avid autograph collector, from his Commonwealth Avenue perch Norcross nurtured the city’s flourishing history culture, taking a leading role at the New England Historic and Genealogical Society, the American Antiquarian Society, and the Bostonian Society. He rose to serve as Cabinet-Keeper for the Massachusetts Historical Society, supervising the intake and cataloguing of major collections including, by April 1920, the library of historian Henry Adams. At the Society’s next meeting, held in the midafternoon of 10 June, Grenville Norcross reported on the Cabinet’s newest curiosity, which has proven a royal mystery ever since:

Paper soldiers on the march, and tin men tilting at swordpoint: these were the first battle ranks that Grenville Howland Norcross, aged 11 in Civil War Boston, led to glory. Between phantom invasions and replays of Antietam with “relics” received as gifts, Norcross gobbled up the military heroics popularized by the era’s dime novels. In a childhood diary that illustrates how “lowbrow” literature grabbed the imagination of a warsick homefront, Norcross chronicled his progress through the antics of Kate Sharp, Old Hal Williams, and Crazy Dan. By 1875, Norcross had outgrown his toy battalions, graduated Harvard, and stepped into a law career. An avid autograph collector, from his Commonwealth Avenue perch Norcross nurtured the city’s flourishing history culture, taking a leading role at the New England Historic and Genealogical Society, the American Antiquarian Society, and the Bostonian Society. He rose to serve as Cabinet-Keeper for the Massachusetts Historical Society, supervising the intake and cataloguing of major collections including, by April 1920, the library of historian Henry Adams. At the Society’s next meeting, held in the midafternoon of 10 June, Grenville Norcross reported on the Cabinet’s newest curiosity, which has proven a royal mystery ever since:

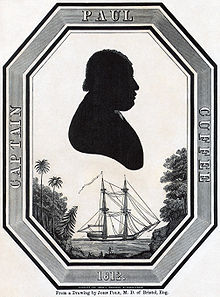

Guest Post: Will the Real Paul Cuffe Please Stand Up?

Today’s guest poster, Jeffrey A. Fortin, is an Assistant Professor of History at Emmanuel College, Boston. He is currently finishing up a book on Paul Cuffe, an African-American Quaker and merchant in the early republic.

Credit cards, electronic banking, online shopping, and a host of other modern forms of commerce did not exist at the turn of the nineteenth century. Merchants throughout the Atlantic relied on reputation and good character when determining a customer’s credit worthiness. Not exactly a foolproof way to do business but seemingly less risky than our fully electronic world of money and banking in twenty-first century America. Yet, identity theft and fraud were still a part of doing business.

Credit cards, electronic banking, online shopping, and a host of other modern forms of commerce did not exist at the turn of the nineteenth century. Merchants throughout the Atlantic relied on reputation and good character when determining a customer’s credit worthiness. Not exactly a foolproof way to do business but seemingly less risky than our fully electronic world of money and banking in twenty-first century America. Yet, identity theft and fraud were still a part of doing business.