We’re pleased to feature this interview with Dr. Ian McKay, the director of the Wilson Institute for Canadian History at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, and Dr. Maxime Dagenais, research coordinator at the Wilson Institute. Dr. McKay is a highly influential historian of Canada, whose books include The Quest of the Folk: Antimodernism and Cultural Selection in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia (1994), Rebels, Reds, Radicals: Rethinking Canada’s Left History (2005), Reasoning Otherwise: Leftists and the People’s Enlightenment in Canada, 1890-1920 (2008), and [with Jamie Swift], Warrior Nation: Rebranding Canada in an Age of Anxiety (2012). He was named the Wilson Institute’s new director in 2015. Dr. Dagenais is a historian of Canada and the United States and holds a PhD in 19th Century British and French North American history from the University of Ottawa (October 2011). He was formerly a L.R. Wilson postdoctoral fellow at the Wilson Institute for Canadian History at McMaster University and a SSHRC postdoctoral fellow at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania (2014-2016), where he was affectionately known as “Canadian Max.” He is the co-author (with Beatrice Craig) of The Land in Between. The Upper St. John Valley, Prehistory to World War One (2009), and is currently working on a research project on the 1837-38 Canadian Rebellions and the American people. Continue reading

We’re pleased to feature this interview with Dr. Ian McKay, the director of the Wilson Institute for Canadian History at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, and Dr. Maxime Dagenais, research coordinator at the Wilson Institute. Dr. McKay is a highly influential historian of Canada, whose books include The Quest of the Folk: Antimodernism and Cultural Selection in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia (1994), Rebels, Reds, Radicals: Rethinking Canada’s Left History (2005), Reasoning Otherwise: Leftists and the People’s Enlightenment in Canada, 1890-1920 (2008), and [with Jamie Swift], Warrior Nation: Rebranding Canada in an Age of Anxiety (2012). He was named the Wilson Institute’s new director in 2015. Dr. Dagenais is a historian of Canada and the United States and holds a PhD in 19th Century British and French North American history from the University of Ottawa (October 2011). He was formerly a L.R. Wilson postdoctoral fellow at the Wilson Institute for Canadian History at McMaster University and a SSHRC postdoctoral fellow at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania (2014-2016), where he was affectionately known as “Canadian Max.” He is the co-author (with Beatrice Craig) of The Land in Between. The Upper St. John Valley, Prehistory to World War One (2009), and is currently working on a research project on the 1837-38 Canadian Rebellions and the American people. Continue reading

Monthly Archives: September 2016

Men of La Mancha

In a certain village of vast early America, whose name I do not recall, a book fell open. Then another. And another. By 1860, many generations’ worth of American readers had imbibed the two-volume work of Spain’s early modern master, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: Don Quixote, or, El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de La Mancha (1605). Cervantes’ metafiction of a mad knight-errant, often hailed as the first Western novel, bustled and blistered with originality. Continue reading

In a certain village of vast early America, whose name I do not recall, a book fell open. Then another. And another. By 1860, many generations’ worth of American readers had imbibed the two-volume work of Spain’s early modern master, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra: Don Quixote, or, El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de La Mancha (1605). Cervantes’ metafiction of a mad knight-errant, often hailed as the first Western novel, bustled and blistered with originality. Continue reading

Making Students Lead Discussion: Three Methods

Image credit: legogradstudent.tumblr.com

I wrote lots of recommendation letters for students this summer, probably because last year was the first year that I taught students in their final undergraduate year, and many of them are looking for or have recently found jobs. I always die a little inside when I read or hear the word “employability,” because I think it’s a jargony term that seems to reiterate the point that a university sells a degree to its customers, the students. I do not think that education should be viewed as such a service, but neither do I think that it’s responsible to entirely eschew discussions of marketable skills that students can mention in their pre- and post-graduate job searches. Not all of them will become professional historians, and given the state of the academic job market, that’s okay! I spend time at the start of each term, in class and in my syllabi, explaining why I think it’s important for students to participate in class discussion. One of my key points is that a student’s class contributions are something that I can and do mention in my recommendation letters. Having spent the summer writing letters for recent graduates I know that I’ve mentioned their contributions in every single letter I’ve written. Lately, my feelings have gone beyond believing that students should participate: I think students should lead discussion. Continue reading

Interview with Carolle R. Morini, Boston Athenæum

T oday’s post is an interview with Carolle R. Morini, Caroline D. Bain Archivist, Reference Librarian, at the Boston Athenæum. Carolle holds a BFA in Photography from the Montserrat College of Art and an MA in History and an MLS in Archives Management from Simmons College.

oday’s post is an interview with Carolle R. Morini, Caroline D. Bain Archivist, Reference Librarian, at the Boston Athenæum. Carolle holds a BFA in Photography from the Montserrat College of Art and an MA in History and an MLS in Archives Management from Simmons College.

Making Utopia a Theme in Early American History

This year I’m overhauling my early American survey course. Not only do I need to make it fit the schedule at my new institution, but because I’m planning to be teaching here for quite a while, I also want to build a course that carries my own signature, and where I can work out some of my own questions and ideas. Survey courses that I’ve taught before—like the one designed by Sarah Pearsall for Oxford Brookes University—have been themed around the violence of empire and slavery. Obviously, those continue to be both central concerns in teaching and the foci of cutting-edge scholarship. But in my search for something different, and for something that might capture the imaginations of my first-year students, I’ve chosen a different path: utopia. Continue reading

This year I’m overhauling my early American survey course. Not only do I need to make it fit the schedule at my new institution, but because I’m planning to be teaching here for quite a while, I also want to build a course that carries my own signature, and where I can work out some of my own questions and ideas. Survey courses that I’ve taught before—like the one designed by Sarah Pearsall for Oxford Brookes University—have been themed around the violence of empire and slavery. Obviously, those continue to be both central concerns in teaching and the foci of cutting-edge scholarship. But in my search for something different, and for something that might capture the imaginations of my first-year students, I’ve chosen a different path: utopia. Continue reading

Making a Webpage for a Conference Paper

I recently had to cancel a trip to a conference. My panel is continuing without me; the chair has graciously offered to read my paper in my place. Partly because of this, I am doing something I haven’t done before: putting together a companion webpage for the presentation.

I recently had to cancel a trip to a conference. My panel is continuing without me; the chair has graciously offered to read my paper in my place. Partly because of this, I am doing something I haven’t done before: putting together a companion webpage for the presentation.

Making companion webpages does not seem to be a widespread practice yet at history conferences, but I do know historians who have done it. For other people who are interested in the idea, I thought I would talk through what I am doing, keeping in mind that many presenters may not have extensive experience making webpages.

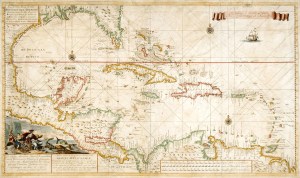

The Continental Toehold Dilemma

“The heart of the English Empire in the seventeenth-century Americas was Barbados,” according to Justin Roberts in his recent William and Mary Quarterly article.[1] That claim is perhaps not surprising—Richard Dunn established the social and economic importance of the island over thirty years ago in his seminal work, Sugar and Slaves. However, Roberts takes that point further by exploring the political ramifications of all of that Barbadian wealth in the West Indies. His article also speaks to a larger sea change in the historiography of the seventeenth-century Caribbean. Continue reading

Review: Matthew Karp, This Vast Southern Empire

This review is cross-posted from Ben Park’s own blog, “Professor Park’s Blog: Musings of a Professor of American Politics, Culture, and Religion.”

Matthew Karp, This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016).

This isn’t your grandparents’ antebellum South. A generation ago it was common for historians to talk about the “regressing” southern states in the decades preceding Civil War. The advent of democracy, the spread of enlightenment, and the triumph of free labor left slaveholders reeling and the slave institution crumbling. Secession, this narrative emphasized, was the last-ditch effort of a flailing boxer on the ropes. But scholarship from the past couple decades have put that myth to rest. Michael O’Brien demonstrated that southerners were intellectuals who contemplated the most sophisticated issues of modernity. Edward Baptist showed how the slave institution increased in strength as the financial staple in America’s capitalistic order. Walter Johnson and Sven Beckert displayed how slaveholders were at the forefront of an increasingly global economy. These and many other works all point to the same crucial revision: slaveholding southerners were “modern,” and their ideas and actions cannot be merely dismissed as remnants of an antiquated age. Continue reading

This isn’t your grandparents’ antebellum South. A generation ago it was common for historians to talk about the “regressing” southern states in the decades preceding Civil War. The advent of democracy, the spread of enlightenment, and the triumph of free labor left slaveholders reeling and the slave institution crumbling. Secession, this narrative emphasized, was the last-ditch effort of a flailing boxer on the ropes. But scholarship from the past couple decades have put that myth to rest. Michael O’Brien demonstrated that southerners were intellectuals who contemplated the most sophisticated issues of modernity. Edward Baptist showed how the slave institution increased in strength as the financial staple in America’s capitalistic order. Walter Johnson and Sven Beckert displayed how slaveholders were at the forefront of an increasingly global economy. These and many other works all point to the same crucial revision: slaveholding southerners were “modern,” and their ideas and actions cannot be merely dismissed as remnants of an antiquated age. Continue reading

The Strange Death(?) of Political History

The glory days of American political history?

Historians are back in the news, this time not as a scolds (“this bit of history in popular culture isn’t historical enough”) but as Cassandras. Recently Fredrik Logevall and Kenneth Osgood, writing under the New York Times print edition headline “The End of Political History?,” bemoan the collapse political history as an area fit for study by professional historians.[1] Jobs in political history have dried up, fewer courses in the subject are offered in universities, few people are entering graduate school to specialize in the subject and hence “the study of America’s political past is being marginalized.” To Logevall and Osgood this marginalization has two tragic effects. Firstly, it denies American citizens’ access to the intellectual tools necessary to historicize our contemporary politics and “serve as an antidote to the misuse of history by our leaders and save us from being bamboozled by analogies, by the easy ‘lessons of the past.’” It also denies historians access to political power, the ability to influence policy and policymakers in the mode of C. Vann Woodward and Arthur Schlesinger Jr. Continue reading

Seeking Sabbatical Advice

It’s a fun time for me to be a Juntoist. I joined the blog while I was ABD, on the brink of defending my dissertation. I had thoughts about research and writing, many untested theories about teaching, and opinions about where historians needed to eat when visiting archives in different cities. This was a blog for junior early Americanists, and I didn’t think too much about how the blog would grow and evolve over the next several (!) years. Definitions of junior scholars (“early career researchers” here in the United Kingdom) vary across the UK. The Arts and Humanities Research Council’s definition is someone within eight years of the PhD or within six years of their first academic appointment. Within my faculty, ECRs include “level 4” staff within four years of being hired or recently hired. Thus when I passed my probation, was promoted to level 5, and became a permanent member of staff, I became a non-ECR by my faculty’s definition but still eligible to apply for AHRC ECR funding and funding from other schemes.[1] All this is a long way of saying that I’m a Not So Early Early Career Researcher™ about to embark on her first sabbatical, and would like your advice about how to approach this period of leave. Continue reading

It’s a fun time for me to be a Juntoist. I joined the blog while I was ABD, on the brink of defending my dissertation. I had thoughts about research and writing, many untested theories about teaching, and opinions about where historians needed to eat when visiting archives in different cities. This was a blog for junior early Americanists, and I didn’t think too much about how the blog would grow and evolve over the next several (!) years. Definitions of junior scholars (“early career researchers” here in the United Kingdom) vary across the UK. The Arts and Humanities Research Council’s definition is someone within eight years of the PhD or within six years of their first academic appointment. Within my faculty, ECRs include “level 4” staff within four years of being hired or recently hired. Thus when I passed my probation, was promoted to level 5, and became a permanent member of staff, I became a non-ECR by my faculty’s definition but still eligible to apply for AHRC ECR funding and funding from other schemes.[1] All this is a long way of saying that I’m a Not So Early Early Career Researcher™ about to embark on her first sabbatical, and would like your advice about how to approach this period of leave. Continue reading