Sowande’ Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016).

Writing a book review a day after Karin Wulf’s entertaining analysis of what makes for a good review might be hubris at its worst, or simply bad timing. And, while I will never have the expertise, style, and prose that made Annette Gordon-Reed’s review of Robert Parkinson’s The Common Cause: Creating Race and Nation in the American Revolution so good, I do hope this review will explore the central ideas of Slavery at Sea in anticipation of a Q&A between the author and The Junto’s own Rachel Hermann tomorrow. Stay tuned for that!

Writing a book review a day after Karin Wulf’s entertaining analysis of what makes for a good review might be hubris at its worst, or simply bad timing. And, while I will never have the expertise, style, and prose that made Annette Gordon-Reed’s review of Robert Parkinson’s The Common Cause: Creating Race and Nation in the American Revolution so good, I do hope this review will explore the central ideas of Slavery at Sea in anticipation of a Q&A between the author and The Junto’s own Rachel Hermann tomorrow. Stay tuned for that!

In the introduction of her new book, Assistant Professor of History and African and African American Studies, Sowande’ Mustakeem, writes that, “not all slaves endured the transatlantic passage in the same way.” That statement serves as the driving force behind an unflinching exploration of the “multiplicity of sufferings” endured by aged, infirm, and infant Africans carried across the Atlantic and into slavery. Despite the simplicity of that premise, Mustakeem’s concise monograph exposes how the focus on young and able-bodied African men as the predominant population of captives held in slave ships overshadows the experiences of the “forgotten” of the transatlantic slave trade. As a result Mustakeem’s narrative lingers on the painful details of what she describes as “a massively global human manufacturing process” that commodified the bodies of young and old, healthy and infirm, female and male (9). Continue reading

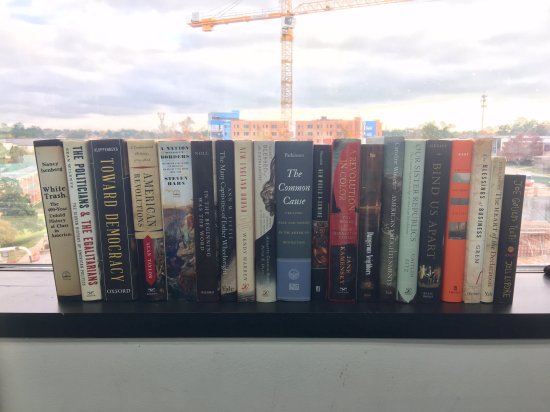

In the past 10 years, we have seen an embarrassment of riches in scholarship that considers race in Early America (broadly understood). The list below is not exhaustive, but highlights some of the recent scholarship. Feel free to add your own favorite recent scholarship in the comments, and keep your eyes out next month, for our CFP for a roundtable on race in Early America.

In the past 10 years, we have seen an embarrassment of riches in scholarship that considers race in Early America (broadly understood). The list below is not exhaustive, but highlights some of the recent scholarship. Feel free to add your own favorite recent scholarship in the comments, and keep your eyes out next month, for our CFP for a roundtable on race in Early America.

Today, we are pleased to offer an interview with

Today, we are pleased to offer an interview with

Following on from

Following on from