Guest Poster Shaun Wallace (@Shaun_Wallace_) is an Economic and Social Research Council-funded Ph.D. candidate at the University of Stirling. His dissertation examines how reading and writing influenced and aided slave decision-making in the early republic. Shaun holds a B.A. (Hons.) and a MRes. from the University of Stirling and is president of Historical Perspectives, a Glasgow-based historical society run by and for graduate students in the United Kingdom.

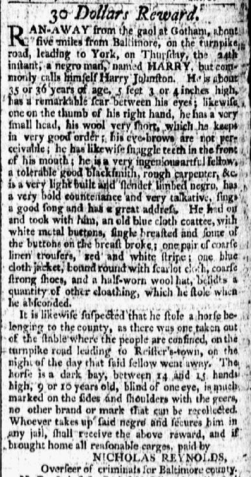

A “very ingenious artful fellow” appears a peculiar description of a runaway advertised for recapture. The advertisement, for Harry or Harry Johnstone, featured in Baltimore’s Federal Gazette newspaper, on May 2, 1800, at the request of Nicholas Reynolds, overseer of criminals for Baltimore County. Harry had absconded from Gotham gaol, near Baltimore. Reynolds described Harry as a “tolerable good blacksmith” and a “rough carpenter.” A “very talkative” slave, he was a man of “great address.” On first impression a relatively congenial description; in actuality, Reynolds’s use of the term “artful” condemned the runaway.[1]

A “very ingenious artful fellow” appears a peculiar description of a runaway advertised for recapture. The advertisement, for Harry or Harry Johnstone, featured in Baltimore’s Federal Gazette newspaper, on May 2, 1800, at the request of Nicholas Reynolds, overseer of criminals for Baltimore County. Harry had absconded from Gotham gaol, near Baltimore. Reynolds described Harry as a “tolerable good blacksmith” and a “rough carpenter.” A “very talkative” slave, he was a man of “great address.” On first impression a relatively congenial description; in actuality, Reynolds’s use of the term “artful” condemned the runaway.[1]

Continue reading

As anyone who has taught the history of slavery knows, it can be challenging. It is an important, but also emotionally loaded subject that can provoke spirited responses from students. Some students are resistant to discussing what they view as an ugly event in the past. Others may become defensive. And, for others, the history of slavery may be personal. The challenge becomes presenting the history in a thoughtful way that will engage students, but does not whitewashing history. Other traumatic events—genocide, war, etc.—can present similar pedagogical challenges.

As anyone who has taught the history of slavery knows, it can be challenging. It is an important, but also emotionally loaded subject that can provoke spirited responses from students. Some students are resistant to discussing what they view as an ugly event in the past. Others may become defensive. And, for others, the history of slavery may be personal. The challenge becomes presenting the history in a thoughtful way that will engage students, but does not whitewashing history. Other traumatic events—genocide, war, etc.—can present similar pedagogical challenges. Antebellum editors were bulk retailers. Whatever else their business involved, it happened at scale, and I’m often astonished by how much prose a nineteenth-century newspaper or magazine editor could churn out in a day. Of course, most of that prose was recycled, and much of it was banal. As a forthcoming article by Ryan Cordell, based on research by the Viral Texts Project at Northeastern University, observes, the most-reprinted antebellum newspaper articles were pieces of “information literature”—not news, but scrapbookable things like an 1853 starch recipe or a clipping about the dietary value of tomatoes.[1] Apparently, antebellum readers welcomed such textual flotsam—but it was especially useful to editors, who needed a steady flood of context-free, easily resized gobbets of writing for their pages.

Antebellum editors were bulk retailers. Whatever else their business involved, it happened at scale, and I’m often astonished by how much prose a nineteenth-century newspaper or magazine editor could churn out in a day. Of course, most of that prose was recycled, and much of it was banal. As a forthcoming article by Ryan Cordell, based on research by the Viral Texts Project at Northeastern University, observes, the most-reprinted antebellum newspaper articles were pieces of “information literature”—not news, but scrapbookable things like an 1853 starch recipe or a clipping about the dietary value of tomatoes.[1] Apparently, antebellum readers welcomed such textual flotsam—but it was especially useful to editors, who needed a steady flood of context-free, easily resized gobbets of writing for their pages. Welcome to another edition of This Week in American History. It has been a busy, yet troubling two weeks.

Welcome to another edition of This Week in American History. It has been a busy, yet troubling two weeks.