This Colonial Couture post is by guest contributor Charmaine A. Nelson, professor of art history at McGill University. Her latest book is Slavery, Geography and Empire in Nineteenth-Century Marine Landscapes of Montreal and Jamaica.

It is a remarkable fact that everywhere that Africans were enslaved in the transatlantic world, they resisted in a myriad of ways. While scholars have frequently examined the more spectacular and violent forms of resistance (like slave revolts and rebellions), a far quieter type of resistance was ubiquitous across the Americas, running away. Where printing presses took hold, broadsheets and newspapers soon followed, crammed with all manner of colonial news. Colonial print culture and slavery were arguably fundamentally linked. More specifically, as Marcus Wood has argued, “The significance of advertising for the print culture of America in the first half of the nineteenth century is difficult to overestimate.”[1] Continue reading

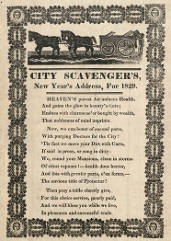

Every day they took apart the city, and put it back together again. New Year’s Day was no different. They worked while dawn, then dusk, threaded the sky, to patch up narrow streets. Lamplighters, an urban mainstay heroicized by

Every day they took apart the city, and put it back together again. New Year’s Day was no different. They worked while dawn, then dusk, threaded the sky, to patch up narrow streets. Lamplighters, an urban mainstay heroicized by  In a certain village of vast early America, whose name I do not recall, a book fell open. Then another. And another. By 1860, many generations’ worth of American readers had imbibed the two-volume work of Spain’s early modern master, Miguel de

In a certain village of vast early America, whose name I do not recall, a book fell open. Then another. And another. By 1860, many generations’ worth of American readers had imbibed the two-volume work of Spain’s early modern master, Miguel de

The baker’s nod, the knight’s blade, the king’s touch: These are three of the main and mostly medieval reasons why I read and write American history. Over the past few days, we’ve

The baker’s nod, the knight’s blade, the king’s touch: These are three of the main and mostly medieval reasons why I read and write American history. Over the past few days, we’ve