When Paul Gilroy wrote his now-classic critique of cultural nationalism in 1995, he conceived a Black Atlantic that was a geo-political amalgamation of Africa, America, the Caribbean, and Europe. Gilroy was particularly interested in the construction of a modern, post-colonial cultural space in which slavery remained a part of modern black consciousness. His book is particularly noted for the introduction of race as a critical consideration in exploring the Black Atlantic.

It is fitting then, that we kick off our week-long discussion of the Black Atlantic with a post by Marley-Vincent Lindsey, which explores considerations of race in the Iberian Atlantic. Subsequent posts will consider Black responses to freedom (and unfreedom), historical narrative, race, and of course, power. Marley-Vincent Lindsey is a PhD student at Brown University. He is interested in writing the history of a Medieval Atlantic, tracing connections of land and labor grants between fourteenth-century Iberia and sixteenth-century New Spain. He also writes about history and the web with Cyborgology, and can sometimes be found tweeting @MarleyVincentL.

An early image of an African conquistador during Cortes’s invasion of Tenochtitlan. While the associated text makes no specific mention of Juan Garrido, historians have often associated this image with Garrido, one of the few known early black conquistadors. Fray Diego Duran, Historia de las Indias de Nueva Espana e Islas de la Tierra Firme (1581), 413. Image credit: People of Color in European Art History.

Juan Garrido was a typical conquistador: arriving in Hispaniola by 1508, Garrido accompanied Juan Ponce de León in his invasion of Puerto Rico, and was later found with Hernan Cortés in Mexico City. Yet his proofs of service, a portion of which was printed by Francisco Icaza in a collection of autobiographies by the conquistadors and settlers of New Spain, made a unique note: de color negro, or “of Black color.”[1] Continue reading

Today, we are pleased to offer an interview with

Today, we are pleased to offer an interview with

Students of the early American republic: I urge you to apply to SHEAR 2016’s

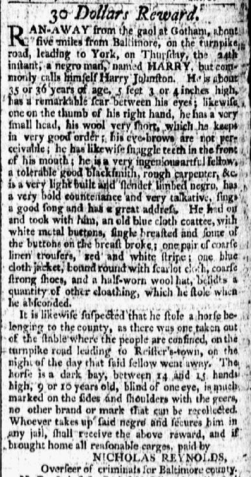

Students of the early American republic: I urge you to apply to SHEAR 2016’s  Terri Snyder is Professor of American Studies at California State University at Fullerton who specializes in slavery and gender. She received her PhD in 1992 from the University of Iowa. In 2003, Cornell University Press published her first book,

Terri Snyder is Professor of American Studies at California State University at Fullerton who specializes in slavery and gender. She received her PhD in 1992 from the University of Iowa. In 2003, Cornell University Press published her first book,

This morning on the other side of the Atlantic, I woke up early in preparation for a seminar on William Otter, whose History of My Own Times closes the list of our readings in my Revolutionary America class. Essentially, Otter was a brawling, violent, white man in the 1800s, living variously in New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. He jumped from job to job while engaging in various aggressive “sprees” against African Americans, Irishmen, and anyone else who seemed a likely candidate before becoming a burgess of Emmitsburg, Maryland.

This morning on the other side of the Atlantic, I woke up early in preparation for a seminar on William Otter, whose History of My Own Times closes the list of our readings in my Revolutionary America class. Essentially, Otter was a brawling, violent, white man in the 1800s, living variously in New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. He jumped from job to job while engaging in various aggressive “sprees” against African Americans, Irishmen, and anyone else who seemed a likely candidate before becoming a burgess of Emmitsburg, Maryland.